The Diplomat Motel is a relic of the golden age of travel. Nestled between freshly built apartments and across from Tony’s Fresh Market on a stretch of U.S. Route 41 that runs on Lincoln Avenue, it’s a glimpse of what this North Side neighborhood of Lincoln Square was like before the Edens Expressway took travelers away from the old highway.

Combing through images online, I find a midcentury postcard of the Diplomat. Painted in peachy pinks and soft blues, the motel is delightful, with its neat lines of windows and a lovely little office. Clusters of sharp atomic diamonds evoke the architecture of the 1950s.

When I moved into the neighborhood in 2022, the Diplomat, still in operation at 5230 North Lincoln Avenue, no longer looked like the kind of building that could be on a novelty postcard. Instead, the motel was a muddy gray, its doors painted green with shocks of red trim. The windows along the sidewalk had been plastered over, a slab of nondescript brown that would press itself into your periphery when you walked past it. You didn’t know, but also you knew, what went on inside the Diplomat, why people would warn in a whisper to never let visitors stay there. When you idled in front, in traffic, the building felt like a bruise on the streetscape.

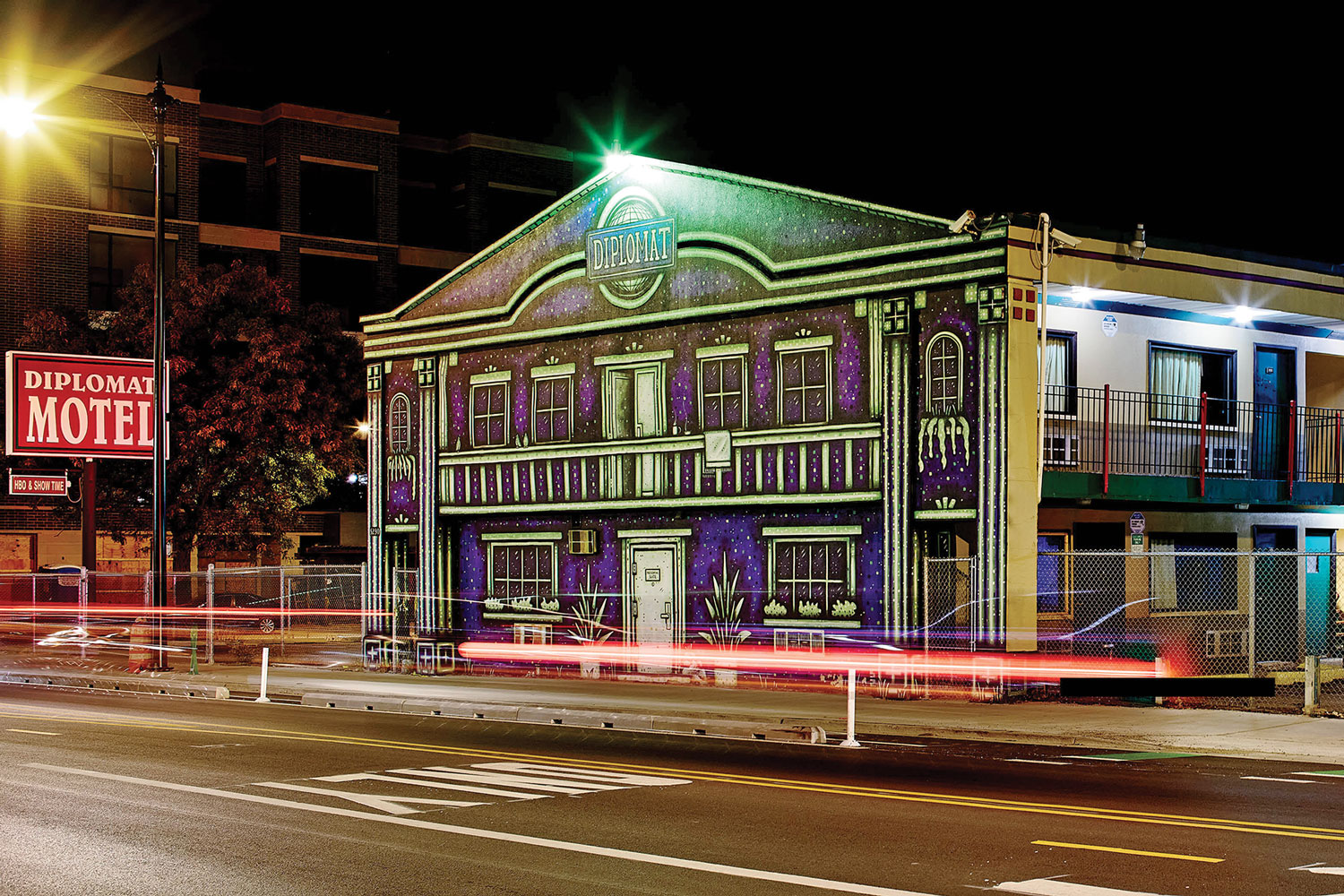

A few months later, Chicago artist Sick Fisher was hired to paint one of his signature trompe l’oeil murals onto the bare brown wall. In bubbly purples and greens, he added cartoonish columns, windows with flower boxes, a balcony rail. A placard on the ground-floor door reads “Presidential Suite”; the door above it opens to nowhere.

That was before the city announced, in 2023, that it was going to buy the motel. That it was going to turn the Diplomat into a transitional housing facility called the Haven on Lincoln, a chance to try something new that could maybe, just maybe, address this city’s struggles with homelessness.

Before then, the mural seemed like an inside joke — who could ever imagine a motel, this motel, with lush plants and a fresh coat of paint? But now, knowing what we know — knowing what will happen to the Diplomat in a few short months — the mural is a game. Turn your head a bit. Blur out the stained curtains, remove the dingy corners. Imagine what this place could be.

It was an early-September Sunday. Summer still had its grip on the city. My husband and I were stuck in traffic on Peterson Avenue and saw, right in front of an abandoned medical tower, a man lying on his back across the sidewalk, his arms and legs outstretched.

“Is he OK?”

“Should we call … ?”

In the seconds that followed, as we waited at the red light, we talked over each other, trying to assess the right thing to do. I dialed 911.

“I — we don’t know if he’s OK,” I began to explain to the operator. “He’s not moving and we’re not sure if he’s … if he’s hurt.”

The light turned green, traffic started moving. We drove away.

By the time we arrived home, only a few blocks away, we could hear the sirens getting closer. Perhaps for that man, we hoped. Maybe it was only heat exhaustion. Or maybe we misread the entire situation and this was just a story of someone trying to catch a beat, trying to get some rest in the midafternoon sun. But it didn’t look that way. And in the split second of decision, when we questioned if we should do anything, I felt myself wonder if really we needed to do anything at all. We sat in traffic, cars chugging bumper to bumper. Surely someone else had called 911; surely someone else had stepped up. But we couldn’t seem to shake the question: What if no one else had?

I’m thinking about this — about the ways in which we show up for our neighbors, about resources, about who’s responsible for what and for whom — on a Monday morning later that month as I make my way south on Lincoln Avenue.

It’s been a few weeks since I’ve driven through this stretch, and I marvel at how quickly this city can change. The new builds have built up, their shadows casting new shapes onto the road’s asphalt. The Diplomat Motel, once a stalwart, strong and foreboding among a sea of single-story strip malls and parking lots, is newly dwarfed by the three-story condo building that’s nearly complete. I pull into one of the Diplomat’s two parking lots, where I meet the man in charge of overhauling the motel.

“Honestly, we were mostly concerned about the solar panels we’re installing on the roof,” Sean McGuire, a senior associate at the architecture firm Gensler, says with a laugh when I ask about the rapidly changing streetscape, now full of multistory buildings that block the sun at times. We’re standing below the motel’s sign, which still beckons potential guests with promises of HBO and Showtime. A city truck idles in the parking lot; a man begins to snake a hose into the drain. “We’re double-checking the sewer and storm line,” McGuire explains as we make our way past the construction fencing and toward the building.

It’s been about a year and a half since the neighborhood got wind that this old motel was going to be converted into something the city was calling “stabilization housing,” and while I’ve spent the better part of that time trying to understand exactly what that entails, until today, I’ve never actually been to the Diplomat. The motel’s transformation into the Haven on Lincoln is a pilot program that will provide housing to homeless people in the throes of addiction and mental illness, without any requirements like sobriety — what’s known as a “housing first” model. And unlike traditional shelters, everyone will get their own room.

“This project is the kind of project that makes people want to study architecture,” McGuire says.

He motions to the parking lot. “All this asphalt will get torn up.” In its place will go a park with trees and shrubs and seating for upward of 75 people. I feel the sun beating down on the blacktop and imagine how pleasing some green space would be. It feels like this strip of Lincoln has been consumed by the dull gray of construction dust for years.

McGuire tells me about a project he worked on in Ohio. It was a neuroscience wellness center, one where the design of the physical space catered to the mental and emotional needs of patients dealing with neurodegenerative diseases. This kind of consideration, which McGuire says is a growing trend in architecture, is also influencing how he, the city, and Volunteers of America Illinois, the nonprofit selected to run the facility, all conceptualize the Haven.

In addition to having private space, every resident will have access to onsite services for medical, mental health, and addiction support. It’s modeled on an earlier city initiative. From April to September 2020, during the height of the pandemic, more than 200 homeless people, all over the age of 50, were placed in rooms at Hotel One Sixty-Six (formerly Cambria Chicago Magnificent Mile) in Streeterville. The impetus was to prevent the spread of COVID, particularly among vulnerable people, so medical services were brought onsite. Residents were given primary care and also treated for psychiatric and substance abuse disorders. If they needed medication, it was delivered to them. Doctors were able to provide consistent care and, over time, build trust — a different path for a group of people whose access to health care is often through emergency services.

At the Diplomat, McGuire swipes open one of the ground-floor rooms with a keycard. The furniture has been removed. The carpet is stained. On the wall is a still life of a fruit bowl.

McGuire tells me that they’re tearing up the carpet in every room, that they’re replacing the drywall and the lighting. “We want to create moments of celebration,” he says, referring to building’s color scheme, which will be anchored by blues and neutrals in order to convey a feeling of fluidity and contemplation. The same is true of the murals planned for the exterior and of the interior lighting, which won’t be too warm, or too sterile, but just right to give the place a little life.

I think about all the times I drove past the Diplomat before it closed and what I saw. In the parking lot, empty cars. In the open-air hallways, abandoned cleaning trolleys and industrial-size laundry carts. Never any people. Never many signs of life. The things that happened at the Diplomat were simultaneously mysterious and overt.

It makes this new openness — the purported transparency of a government program — feel almost strange. When the Haven opens in the late spring or early summer of 2025, it will house 40 people, all of whom will be what the city considers “high utilizers” of the system: individuals with repeated interactions with emergency rooms, 911 services, or shelters. They’ll be referred by the crisis support systems they’ve cycled in and out of for years and given direct access to the services they need to, hopefully, get back on their feet for good.

The rooms, standard motel size at 12.5 by 20 feet, are small, but big enough to allow a bit of storage. There’s a shower, a sink. McGuire points out space for a mini fridge. It’s the kind of place that’s comfortable without being too comfortable, which isn’t a bad thing. Residents won’t be here for very long — only three to six months — before they transfer into something more permanent. At least that’s the plan.

The Diplomat is one of nine motels that remain on Lincoln Avenue. Their decline has been steady since the Edens opened in 1951, and all have devolved from quaint accommodations into something more suspect. Neighbors have only their suspicions about what happens behind the drawn curtains and peeling paint — hunches that are occasionally confirmed when a guest throws something through a window in a fit of rage or the news reports that someone else got shot in the parking lot. But these motels have also evolved to fill gaps in the city’s housing landscape. At around $60 a night (often far less if you’re paying by the month), they’re not necessarily cheaper than a market-rate apartment, but you don’t need a deposit or a credit check. The only thing you need to qualify for a room is cash.

“It’s no way to live, the motels,” Glenn Hamilton tells me over the phone. We’ve never met in person, but he’s active on the neighborhood Facebook group. He was one of the first people to respond when I posted about wanting to talk with neighbors about the Diplomat.

“I live 3 blocks away and I’d be interested,” he wrote. “I own two similar type hotels near Chinatown so I know the pros and cons.”

That motels are already functioning as semipermanent housing seems to be an open secret. “We had to relocate a lot of folks that were living there,” Nancy Hughes Moyer, CEO of VOA Illinois, says of the Diplomat. “I think we were a little surprised by how many.”

There have been five overdoses at Hamilton’s buildings; he’s had to evict seven people. In one of his motels, there’s a lady on the first floor who’s addicted to crack and keeps everyone up at night, screaming. His other motel, though, he’s been able to turn around. It’s inhabited mostly by seniors living on Social Security. He charges them $500 a month for a room and shared bathroom. Hamilton installed cameras to keep an eye on the place.

That motels like these are functioning as semipermanent housing seems to be the city’s open secret. Hamilton says he knew when he bought them that they were more an investment in low-income housing than anything else.

A few weeks earlier, Nancy Hughes Moyer, CEO of VOA Illinois, had alluded to the same thing when I asked whether the Haven would open by December 2024, as originally planned. “The acquisition [of the Diplomat] took a little longer than expected,” she told me. “We had to relocate a lot of folks that were living there. I think we were a little surprised by how many.”

For those who wanted it, relocation meant being placed in another VOA facility or qualifying for rental assistance. But, according to Hughes Moyer, some residents of the motel opted to simply move to another motel: “They preferred to keep their commitments rather loose.”

Michael is tall and has a firm handshake. He doesn’t say, but I’d guess he’s in his late 40s or early 50s. The day I meet him, he’s wearing a long black sweat-wicking shirt and black nylon shorts. He lifts up his baseball cap to wipe his brow, then sets it on the back of his head.

“I’ve been raking for three hours,” he tells me, taking a drag of a cigarette. “I’m exhausted. Let’s go sit down.”

I follow him to the edge of Gompers Park in North Mayfair, where a line of around 20 or so tents runs parallel to a chainlink fence. A few cluster together, but most stretch out along the concrete path near the park’s perimeter.

Michael, who declined to give his last name, walks toward a little patch of dirt that he’s raked clean of leaves and trash. Under a series of pop-up nylon canopies sitting close to the ground is a collection of small grills. I follow Michael into a blue-and-gray tent, the one closest to the fence. Even though I have to duck my head as I enter, it’s bigger than I thought from the outside. There are three futons, arranged in a U, and a wooden side table. It feels more like a living room than a tent.