In 1934, Bobsy Goodspeed, seated beneath a portrait of her by Bernard Boutet de Monvel, relaxes at her lush Lincoln Park apartment; the architect David Adler designed the space.

|

|

Gertrude Stein, the rotund godmother of modernism, returned to the United States from her home in France for the first time in three decades. At 60, after years of writing fiercely obscure and little-read texts, Stein had recently scored a popular hit with The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas—a title that masked the fact that the book was written by, and had as its principal subject, Gertrude Stein. Though reluctant at first, Stein had agreed to follow up the book with a cross-country lecture tour of the United States. Accompanied by Alice Toklas, her lover, girl Friday, and alter ego, Stein arrived in New York on the SS Champlain on October 24, 1934, only to discover that, to her surprise and occasional confusion, she had become a high-wattage celebrity.

Two weeks later, as it turned out, a production of her opera Four Saints in Three Acts, written with the composer Virgil Thomson, was being staged in Chicago at the Auditorium Theatre. Earlier that year, the opera had been a surprise hit on Broadway; its quizzical refrain—"pigeons on the grass alas"—had even become a popular catch phrase. But Stein, still in France, had missed that excitement, and now, because of the demands on her time in New York and the limitations of train travel, it appeared she would miss the fun in Chicago, too.

Nonsense, said her friend Bobsy Goodspeed, telephoning from Chicago. Take the plane. Which was just like Bobsy.

Known as Bobsy since she was a girl—the name had stuck, even though Bobsy was now 41—Elizabeth Fuller Goodspeed was the president of the Arts Club of Chicago and a vivacious, almost unstoppable force. So on the afternoon of November 7, 1934, the day of the opera’s Chicago opening, Stein and Toklas hurried to Newark Airport in New Jersey for their first airplane ride ever.

After an uneventful flight, the plane landed to a crowd of reporters and curiosity seekers at Chicago’s Municipal Airport (today it’s called Midway). Bobsy was waiting with her chauffeur-driven limousine and spirited Stein and Toklas to her luxurious Lincoln Park apartment. That night the Auditorium overflowed with the cream of Chicago society, drawn by the hype surrounding Four Saints, as well as by the promised presence of Stein and Thomson, who would conduct the orchestra. Stein wore a prune-colored silk gown ornamented at the neck with an oval brooch studded with diamonds, while Toklas, her bobbed and waved hair set off by enormous gold earrings, wore a ruffled navy taffeta gown. The pair watched the performance with Bobsy, and when the final curtain fell, they went backstage to congratulate the cast. "The first act seemed so strange and new," a gratified Stein told reporters. "Until tonight I’ve always heard the music inside myself, and now for the first time I’m hearing it outside."

Following the opera, Bobsy held a supper party at her apartment. For both the writer and her hostess, it was a supreme moment of personal and public triumph. "Of the many courses," wrote Toklas in her famous 1954 cookbook (the one with the recipe for hashish brownies), "I only remember the first and the last, a clear turtle soup and a fantastic pièce montée of nougat and roses, cream and small coloured candles." Toklas included Bobsy’s recipe for turtle soup in her cookbook, and today that limpid concoction is the rare reminder of a significant but forgotten Chicago socialite, a spirited woman who, on closer inspection, deserves a more substantial memorial than what Toklas called a "tasty, nourishing but light soup."

* * *

Photography: (Goodspeed) Conde Nast Archive/Corbis; (Stein) Carl Van Vechten/Courtesy of the Van Vechten Trust and Henry W. and Albert A. Berg collection of English and American Literature, The New York Public Library

Young Bobsy, a darling of the society pages, depicted in the Tribune in 1916

I caught my first glimpse of Bobsy Goodspeed last fall while reading Janet Malcolm’s latest book, Two Lives: Gertrude and Alice. Over the course of three decades, Malcolm, a regular contributor to The New Yorker (where portions of Two Lives first appeared), has written a number of books that, among other things, explore the nature of truth and the art of the storyteller. In Two Lives, Malcolm examines how Gertrude Stein and Alice Toklas, two well-known Jewish lesbians, managed to survive in France during the deadly and oppressive Nazi occupation. She concludes that the pair endured thanks in large part to the help they received from their good friend Bernard Faÿ, a French scholar who received a life sentence in prison following World War II for collaborating with the Nazis.

Two Lives is a valuable book, its significance residing in the important contributions—interpretive, textual, and biographical—it makes to Stein scholarship. (It’s also a pleasure to read.) But near the midpoint of her book, almost as an aside, Malcolm quotes a 1934 letter from Faÿ. Writing to Stein, he describes Bobsy Goodspeed as "a good-looking, silly-clever Evanston lady, wife of the foremost trustee and lover of the wife of the president of the University of Chicago." Wow! As lurid, gossipy bombshells go, that one’s pretty good, even if it does demand a little deciphering (and even if Malcolm did slightly alter the original language in Faÿ’s letter).

|

|

In 1934, the 35-year-old Robert Maynard Hutchins, education’s wunderkind, was in the fifth year of his 16-year tenure as the president of the U. of C. (from 1945 to 1951 he would serve as the school’s chancellor). He and his wife, Maude Phelps Hutchins, made a striking couple—they were both tall, darkly handsome, and terribly smart—though Maude had a reputation for a chilly aloofness. An artist and aspiring writer, she made it absolutely clear she had no intention of hosting teas or otherwise shouldering the traditional duties of a university president’s wife. She did make friends with a few high-placed Chicagoans, however, among them Mr. and Mrs. Charles Goodspeed. Called Barney by friends (his middle name was Barnett), Charles Goodspeed was, among other things, a trustee at the University of Chicago—and Barney was married to Bobsy. So what Faÿ is telling us is that Maude and Bobsy were having an affair, a bit of news that once would have set wagging tongues aflame all across Chicago.

Given the involvement of Robert Hutchins and his wife, Faÿ’s assertion still resonates today. And though it runs counter to every unwritten rule in the storyteller’s handbook, let me tell you up front that for all I could discover, that bit of news remains nothing but rumor. If you are following this story merely to catch Bobsy and Maude entwined in erotic embrace, stop reading now. That’s not going to happen.

|

|

But as I tried to prove (or disprove) that rumor, I got to know and become half-obsessed with the remarkable Bobsy Goodspeed. In her day—in those years between the two world wars—there was no brighter light in the Chicago firmament than Elizabeth Fuller Goodspeed. Pretty, rich, accomplished, mischievous, she orchestrated a whirlwind of social activities in the city and beyond. Yet Bobsy was much more than the stereotypical Chicago socialite circa 1934. The roles she played not only served Chicago society but also advanced on several fronts—art, music, literature—the local course of modernism. To take one instance alone, Gertrude Stein might never have visited the United States nor developed her special fondness for Chicago if not for Bobsy. Neither would Stein have met the writer Thornton Wilder, with whom she developed the most important new friendship of the last decade of her life. Yet for all most people remember about Bobsy today, she might well have never existed.

Prompted by Faÿ’s letter, I began poking around, looking for Bobsy in famous people’s letters and in the footnotes to scholarly texts. She is a fleeting presence there, appearing suddenly and briefly before vanishing back into the shadows. Bobsy began coming into sharper focus only when I started digging through old newspapers and encountered that Domesday Book of the early decades of the 20th century: the society pages.

* * *

Photography: Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library

A party at the Goodspeeds’: (from left) Bobsy; Stein; the Tribune literary critic Fanny Butcher; Butcher’s husband, Richard Bokum; Alice Roullier (a Chicago gallery owner); Toklas; and Thornton Wilder

In 1916, the year Elizabeth Fuller married Charles Goodspeed, the well-heeled son of a rich and inventive Ohio industrialist, Chicago had seven major daily newspapers. In the days before TV and radio, most Chicagoans religiously followed at least one of these papers to learn about the latest happenings in politics, business, sports, and the arts. An essential part of this mix was the society pages, which minutely chronicled the lives of the city’s elite: their parties, their favorite causes, their exotic travels; their clubs, their domiciles, their clothes. Interest in these stories, written by women whose identities were cloaked in suggestive pen names—Pandora, Cousin Eve, Madame X—extended beyond the upper class. One has only to recall the broad appeal of the elegant Depression-era movies starring Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers to understand the fascinating spell once cast by stories depicting the fairy-tale world of high society.

The society pages, however, could be terribly one-dimensional. In that domain, husbands were virtually nonexistent, their being confirmed only in the names borne by their wives. As I read through pages and pages (and years and years) of society columns, I began to wonder if Bobsy’s father—Dr. Charles Gordon Fuller, a specialist in diseases of the ears and eyes at several Chicago hospitals—had died prematurely. For though I would regularly spot Mrs. Charles Gordon Fuller (Bobsy’s mother) at different events around town, I despaired of ever catching sight of her husband. Only at Bobsy’s wedding does Dr. Fuller briefly emerge, blowing kisses to the bridesmaids from the aisle of Michigan Avenue’s Fourth Presbyterian Church. And only at her death do we learn the first name of Bobsy’s mother: Isabella.

Good-looking, smart, and preternaturally chic, Bobsy frequented those pages as often as the city’s brighter lights—among them, the second and third generations of Armours, McCormicks, and Palmers. Born in 1893, she grew up in a big house on the Evanston lakefront with her sister, Dorothy. (Dorothy’s September 1910 wedding, on the terraced lawn of Daniel Burnham, the Fullers’ friend and neighbor, occasioned Bobsy’s first mention in the press.)

Educated at the Villa Dupont in Paris—a boarding school for American girls run by her aunt and namesake, Elizabeth White—Bobsy acquired an early appreciation of the arts and a love for Europe, predilections she would nurture throughout her life.

Bobsy returned from Paris in the summer of 1913 and continued her studies at the Art Institute of Chicago. She made her formal debut in 1914. By then the Fullers had left the Evanston house and resided at The Virginia, the sumptuous hotel at Rush and Ohio streets where Harriet Monroe, the founder of a new magazine called Poetry, also lived. Like her mother, a onetime president of the Friday and Fortnightly clubs—influential ladies’ groups that sought to refine Chicago’s rough edges—Bobsy took an active role in the local women’s organizations. The "acknowledged belle" of North Side society (according to the Chicago Tribune), she also found time to act and dance, performing Ivan Caryll’s Pink Lady Waltz at a May 1915 benefit for the field hospitals in war-torn France or starring in Cousin Jim, a locally produced movie whose premiere raised about $18,000 for the American Red Cross.

Following her November 1916 wedding to Charles Goodspeed, Bobsy and her husband resided at 191 East Walton Place (today, the address is a hotel loading dock). After the United States entered World War I, Barney shipped off for France as a captain of infantry. With the armistice—Bobsy appeared as New France at a December 1919 victory ball at the Palmer House—the Goodspeeds, who never had children, settled into a routine of travel, charitable benefits, and social events. Barney, who maintained his connections to his late father’s Ohio steel company, served on the boards of the University of Chicago, the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, the Art Institute, Presbyterian Hospital (a forerunner of Rush University Medical Center), and other organizations. He was also a stalwart of the Republican Party, serving as its national treasurer during the 1936 and 1940 presidential campaigns.

As for Bobsy, the newspapers regularly tracked her public appearances: at the symphony, say, in a gown of pink embroidered crêpe draped over pink charmeuse, or gracing a performance of the Ballets Russes, a corsage of white camellias setting off her dress of coral velvet and tulle. But her sense of social obligation also compelled Bobsy toward a life of service, though she may have defined that term broadly. She played a major role with the Arts Club of Chicago—she served as its president from 1932 to 1940, even redesigning its Wrigley Building headquarters—and she was an enthusiastic member of the Junior League. The Tribune deemed her management of the 1924 Billboard Ball, which raised more than $50,000 for the Illinois Children’s Home and Aid Society (one of Bobsy’s favorite causes), "the greatest financial success in Chicago’s history of charitable affairs."

The epicenter for Bobsy’s activities was her home. Around 1927, after a decade on Walton Place, she and Barney moved into the 18-story building at 2430 North Lakeview Avenue in Lincoln Park (the building survives). Adorned with paintings by Picasso, Calder, and Matisse—as well as with two gorgeous paintings of Bobsy, one by Bernard Boutet de Monvel and another by the American impressionist Martha Walter—the elegant apartment served as a command post from which Bobsy organized her own affairs and others’. "’Bobsy’ Goodspeed is the busiest person in town," insisted the Tribune. "She has two telephones beside her bed, and both are in use constantly from 8:30 until 11 every morning."

Bobsy’s home also served as a showcase for her latest artistic discoveries. Years later, Fanny Butcher, the Tribune‘s literary critic, remembered with obvious fondness the pleasant times she had spent there. The guests varied—on one occasion, Butcher got a cryptic call from Bobsy that led to a private dinner with the French writer André Maurois and the former U.S. president Herbert Hoover—but Butcher reserved her most rapturous recollections for the musicians who visited, among them the pianists Artur Rubinstein and Vladimir Horowitz, who gave his first Chicago performance at a private concert arranged by Bobsy. Invited to the Goodspeeds’ home, George Gershwin was making small talk with Butcher when Bobsy floated into the room wearing a white crêpe de Chine dress that was more negligee than tea gown. "The apparition, I felt, was not what Gershwin had expected," wrote Butcher in her autobiography, Many Lives—One Love. "Before my eyes I saw the internationally famous composer turn into a young man dazzled."

* * *

Photography: (Image 1) Charles Goodspeed/Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Tolkias Papers, Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library

|

|

When not at home in Chicago, Bobsy ventured into the remote corners of the world. Between the two world wars, she apparently traveled to Europe most summers, looking to encounter the latest writer, painter, or musician. (On one of these trips, in 1934, she met Gertrude Stein—at her country retreat in Bilignen, situated in France’s Rhone Valley—and encouraged her to come to Chicago). In the early years of their marriage, Bobsy and Barney also traveled to Japan, and at some point they explored the Alaskan wilderness, perhaps journeying as far north as the Arctic Circle. But none of those trips compared to the seven-month voyage around the world the Goodspeeds made in 1925 with two of their friends: John T. McCutcheon, the 54-year-old editorial cartoonist for the Tribune, and his wife, Evelyn, the 30-year-old daughter of the renowned North Shore architect Howard Van Doren Shaw.

The two couples departed Chicago on January 3rd and sailed from San Francisco to Honolulu four days later. From there, they headed to the remote reaches of the Pacific, collecting grass skirts and dolphin-tooth necklaces in New Guinea, escaping the equatorial heat of the Spice Islands with moonlight swims in shark-infested waters. By May they had reached Beijing, where they made arrangements to travel to Ulan Bator, the capital of Mongolia. The Chinese warlord Feng Yuxiang forbade the expedition, but the travelers surreptitiously went on with their plans. "We got our corduroy suits," wrote McCutcheon to a friend in Chicago, "our sheepskin sleeping bags, borrowed a couple revolvers, and [to throw the authorities off the scent] announced that we were going [only as far as] Kalgan," General Feng’s most distant outpost. (Known today as Zhangjiakou, the city is about 100 miles northwest of Beijing.)

At dawn on the morning of May 16th, the travelers drove out from Kalgan in an open Dodge touring car heavily loaded with supplies. After two long days of travel, the foursome confronted the Gobi, which McCutcheon described as "flat as a billiard table." They followed a trail across the desert, where they were besieged by a fierce gale that flung sand into their faces like hot needles. The sand also infiltrated the car’s magneto and carburetor, and when the storm let up, the Dodge wouldn’t start. Far away to the south, McCutcheon spotted a group of yurts (Mongol huts), but how to get there? Bobsy and Evelyn had a solution: They stood up in the car holding a big, broad sheepskin coat between them. The men gave the Dodge a shove, the coat filled with wind, and the car took off, said McCutcheon, like "a regular ship of the desert." They reached the yurts, where the Mongol residents helped repair the car.

Two days later the Goodspeeds and the McCutcheons reached Ulan Bator. An officious customs inspector insisted on checking every article in the Dodge, and he spread the travelers’ belongings across a field covered in manure. "No secrets were left undisclosed," said McCutcheon, who, with his traveling companions, refused to show any sign of irritation. A few days later, after Bobsy and Evelyn became the first women to enter the sacred precincts of Ulan Bator’s Gandan temple and lay eyes on its great gilded Buddha, the travelers returned safely to Beijing.

The rest of the trip must have seemed anticlimactic. The Trans-Siberian express carried the travelers to Moscow, where they saw Lenin’s preserved corpse. Eventually they ended up in Paris, and in July the quartet sailed from London on the Leviathan, bound for New York. At the end of the month they were back in Chicago, where Bobsy and Evelyn, looking svelte in the latest Parisian couture, greeted friends at the annual Lake Forest horse show, their round-the-world trip already a memory. Likely nothing surpassed that experience until nine years later when Bobsy welcomed Gertrude Stein to Chicago, a culminating moment for both the infamous writer and her charming hostess.

* * *

Photograph: Chicago Tribune photo

The opera singer Claire Dux Swift (seated) with (from left) Fanny Butcher, Bobsy, Stein, and the Goodspeeds’ parrot

Gertrude Stein’s tour of the United States in 1934 and 1935 preoccupied her for the rest of her life. The questions it provoked—about identity, memory, and eternity—figure prominently in her final writings, most notably in the chatty book she entitled Everybody’s Autobiography. While pondering those questions, the book also exudes a real warmth prompted by the sights Stein had seen, the adulation she had received, the new friends she had made, and the big Midwestern city she came to love. As Stein put it (eschewing the commas she feared enfeebled her writing): "Chicago besides being an adventure was home."

After their quick overnight visit to see Four Saints on November 7, 1934, Stein and Toklas returned to Chicago at the end of the month for an extended stay. They split their time between The Drake hotel and the Goodspeeds’ apartment, where Toklas had other opportunities to enjoy what she called Bobsy’s "perfect cuisine." Stein signed books at Marshall Field’s and delivered lectures at the Arts Club, the Friday Club, the Chicago Woman’s Club, and the Renaissance Society. Bobsy took her twice to the opera and threw a number of dinner parties in her honor (one ran so late that Barney appeared in his pajamas and told everyone to go home). But Stein’s most significant moments here, probably set in motion by Bobsy, involved the University of Chicago, its president, Robert Hutchins, and two of his closest friends and colleagues: the philosopher Mortimer Adler and the writer Thornton Wilder, a professor of literature at the university who had won a Pulitzer Prize in 1928 for his novel The Bridge of San Luis Rey (and who would win two more for the plays Our Town and The Skin of Our Teeth).

Stein met Wilder on November 25th (he and Bobsy were already close friends), and the two hit it off immediately. Two days later, Wilder joined Stein, Toklas, and the Goodspeeds for dinner at the President’s House on the U. of C. campus. The dinner itself proceeded pleasantly enough. Hutchins and Adler were both absent—they were conducting one of their innovative Great Books classes—so Maude Hutchins presided. A graduate of the Yale School of Fine Arts, Maude, an accomplished artist, had a studio in the carriage house behind the President’s House. There was often a shocking sexual undercurrent to her work—one of her annual Christmas cards featured a nude rendering of what was clearly her pubescent daughter Franja—and Maude, a tall, beautiful brunette, projected a strong erotic aura of her own: plied with martinis, a staple of the Hutchinses’ evening routine, Adler (as he explained it in his 1977 autobiography, Philosopher at Large), suffered "a state of embarrassed excitement" when first he met Maude.

So, were Maude and Bobsy lovers? At this writing, no evidence exists to answer that question. Their husbands were colleagues, and the two women were certainly friends, visiting each other’s homes and attending a variety of entertainments together. But the only suggestion of an affair remains Bernard Faÿ’s letter, and though Faÿ certainly had the opportunity to gather such information—a French scholar devoted to U.S. history and literature, he had visited Chicago while lecturing at Northwestern University in 1933—his reputation as an unlikable scoundrel (and this based on the testimony of his friends) undercuts his credibility.

After dinner concluded at the President’s House, Maude led her guests to the upstairs sitting room. As Wilder settled into a chaise longue, Hutchins and Adler arrived, tired from their long day. Stein immediately confronted them, asking, "Where have you been, Hutchins, and what have you been doing?" Startled by the force behind the question—"the energy Gertrude exuded in a small room hit one like Niagara Falls," Adler wrote in his account of the event—Hutchins made the mistake of addressing his interrogator as Miss Stein. "Don’t call me Miss Stein," barked Stein. "Call me Gertrude Stein." Things went downhill from there.

Hutchins tried to explain the philosophy behind the Great Books program, and Adler produced a list of the books they were discussing, many of which had originally been written in Greek, Latin, and French. The students, it turned out, were reading the books in English translation, which infuriated Stein, who badgered Hutchins as she paced back and forth. "The argument soon turned to the real meaning of ‘ideas,’ and, naturally, from that moment on, grew into a great altercation," wrote Bobsy in a letter to the gossip columnist and celebrity hostess Elsa Maxwell.

Barney Goodspeed jumped to Hutchins’s defense, as did Adler. "I decided that Gertrude needed a dose of her own medicine," he later wrote. "I began to ask her questions, one after another, with gathering force and rising pitch." Stein (in Bobsy’s written account) responded by approaching Adler and pointing at him. "Look at your forehead," she shouted. "It is narrow, narrow. With your dialectics, you could prove anything to me, but, of course, you would be wrong." And with that, she whacked him on the head.

As if on cue, a maid entered the sitting room. "Madame," she announced, "the police." Adler turned white and rose to his feet. The room filled suddenly with laughter. Unbeknownst to the party’s late arrivals, the Tribune‘s Fanny Butcher had arranged for Stein and Toklas to ride around that evening with a couple of Chicago homicide detectives. ("The way I felt about her at that moment, I wished they had [arrived] earlier and taken her for a ride Chicago-style," wrote Adler.) The two women thanked their hosts and prepared to leave. At the doorway, Toklas turned to Adler. "This has been a wonderful evening," she said. "Gertrude has said things tonight that it will take her ten years to understand."

Not one to hold a grudge, Hutchins, probably encouraged by Wilder, later asked Stein to return to Hyde Park in a few days to lead a class on Aristophanes and epic poetry. Impressed by her ability to draw out the students in the poetry class, Hutchins arranged for Stein to come back for the university’s spring session to teach for a couple of weeks. (According to Richard Goldstone, a biographer of Wilder, Hutchins shelved a plan to offer Stein a permanent position at the university.)

On Wednesday, December 5th, Stein threw a dinner party for her Chicago friends and presented them with Christmas gifts: autographed copies of her books. (Bobsy gathered Stein’s handwritten messages and published them as a booklet called Chicago Inscriptions.) On Thursday morning, she and Toklas caught a morning plane to Madison, Wisconsin, the next stop on their national tour.

On February 24, 1935, Stein and Toklas returned to Chicago for another extended stay. Thornton Wilder turned over his Drexel Avenue apartment to them, and there Stein, delighting in the snowy vistas of the Midway, wrote the four lectures on narration that she would deliver at the U. of C. during the first two weeks of March. (Those lectures each drew about 500 students; Stein conducted smaller classes with 30 students selected by Wilder.) She also found occasions to socialize with Bobsy, just back from a winter getaway in Arizona.

Stein and Toklas flew to Dallas on March 17th, but, making their way back toward New York and France, they returned for one final Chicago visit on April 19th. Again they stayed at the Goodspeeds’ apartment, where Bobsy threw them a special dinner. "Gertrude was really a very good guest," Bobsy recalled years later. "She entered into everything with the greatest enthusiasm. She had a rollicking charm that was contagious."

An amateur filmmaker, Bobsy made a short movie that evening. It reveals Stein crammed on a long couch with Toklas and others, while Wilder sits off to the side on a piano bench. Seated on the floor, her fabled charm and mischievous eyes on full display, Bobsy holds a large paper flower and flirts playfully with Fanny Butcher’s husband. Later we see Thornton Wilder, on his feet now, gesturing grandly with the flower and delivering a speech that reduces everyone to laughter. Oh, for a lip reader.

On May 4th, finally back in New York, Stein and Toklas boarded the same boat that had brought them to America. "It was not until we were on the Champlain again," Toklas wrote wistfully in her cookbook, "that I realised that the seven months we had spent in the United States had been an experience and adventure which nothing that might follow would ever equal."

* * *

Photograph: Yale Collection of American LIterature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library

|

|

As things turned out, Toklas was absolutely right. With war looming (and eventually exploding across Europe and Asia) and time taking its toll, the years following Stein’s U.S. tour were a slow but inexorable descent. Suffering from mental burnout, Thornton Wilder visited Stein and Toklas in France in July 1935. Bobsy was there, too, and she shot home movies documenting the visit: Stein hoeing the garden at Bilignen (a task she would never have performed if the camera weren’t rolling); Toklas and the couple’s beloved dogs, Basket and Pepe, walking among the boxwoods.

In February 1937, Bobsy hosted a dinner inaugurating Chicago’s newly decorated Arts Club dining room. Most of the women who attended wore black frocks and other sedate garb; Bobsy, noted the Tribune, "presided over the revels attired in a Grecian costume." She continued to stand out wherever she went: a golden apparition—she was "gilded throughout," noted the Tribune, "eyebrows and hair too"—at a Chicago Architect’s Ball, or "looking like a Matisse" in a black-and-red-striped bodice and skirt at an Arts Club performance by the voodoo chanteuse Elsie Houston. In May 1937, the Goodspeeds attended the coronation of England’s George VI; Bobsy came back doing a dead-on imitation of Wallis Simpson, the American divorcée who had precipitated the upheaval among the British monarchy.

But time was catching up with Bobsy. In August 1939, Wilder saw her at Weeping Willows, the house in Cape Cod that she and Barney had inherited from her mother-in-law. "Her hair is greyer," he wrote Stein, "but she is as pretty and sure of herself as ever." That November, a newspaper article about Chicago opera lumped Bobsy in with the city’s "old guard."

The beginning of World War II led to even more drastic change. Stein and Toklas disappeared behind the wall of Nazi occupation; though in his 40s, Wilder enlisted in the service, ultimately rising to the rank of lieutenant colonel in the Army Air Forces. As she had done a quarter of a century earlier, Bobsy channeled her energies into a variety of fundraisers that supported the war effort. But that didn’t mean a girl couldn’t still have a little fun. In October 1942, one society scribe noted that military uniforms and otherwise informal attire had now become de rigueur at Chicago Symphony concerts. As the Tribune noted, there was one exception: "It remained for Mrs. Charles B. Goodspeed, who was making her first appearance after a summer in the east, to introduce the ‘short’ evening frock to concertgoers. Mrs. Goodspeed, who is noted for her chic, arrived in a midcalf length black chiffon dress trimmed with black lace around the bottom of the skirt."

The war in Europe also meant no more trips overseas. The Goodspeeds now regularly escaped the Midwestern winters in Arizona at a luxe resort outside Phoenix called Castle Hot Springs. "Barney Goodspeed informed us that he had been coming to the springs every year since the [first] world war," wrote a Tribune reporter, "and that he had no intention of ever staying away."

* * *

Photograph: Chicago Tribune photo

Stein writing at the Goodspeeds’ apartment

For many, the surrender of Germany and Japan in 1945 marked a new beginning. For others, it was a final curtain coming down. Stein was the first to go, dying in a Paris hospital in July 1946 after an unsuccessful operation to remove a cancerous tumor from her stomach. Following her partner’s death, Toklas continued her friendship with Bobsy, cooking her lunch on at least one occasion when the Chicagoan visited Paris. After Faÿ’s arrest and life sentence for his wartime activities—his collaboration with the Nazis likely led to the deaths of hundreds of French Freemasons, Faÿ’s particular bête noire—Toklas turned to Bobsy and other friends to help secure his freedom. "Is there any other way of working the miracle—can nothing be done," she pleaded with Bobsy in an October 1946 letter (like Stein, Toklas abstained from using the question mark). "To me it has become a sacred trust—it was so near to Gertrude." (As it turned out, Faÿ eventually escaped to Switzerland; he died in 1978.)

In February 1947, alone in her Paris apartment, Toklas contemplated the famous 1906 portrait of Stein by Pablo Picasso, soon destined to depart for the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. "I cant bear to think of its not being here," she wrote Bobsy. "Gertrude always sat on the sofa and the picture hung over the fireplace opposite and I used to say in the old happy days that they looked at each other and that possibly when they were alone they talked to each other. . . . I send my dearest love to Barney and to you. I think of you constantly." Poverty-stricken and at odds with Stein’s family, Alice Babette Toklas died in Paris in 1967.

By the time of that 1947 letter, Barney had already been ill for several months, confined to Chicago’s Presbyterian Hospital. In town for a concert, the pianist Artur Rubinstein stopped by for a visit in January 1947, performing an impromptu concert for the hospital staff. Hoping that the Arizona desert might provide a cure, Barney and Bobsy traveled to Castle Hot Springs, but Barney died there on February 23rd at 62.

The next casualty was the Hutchinses’ marriage. No longer able to endure his wife’s shrewish and erratic behavior, Bob Hutchins walked out of the President’s House early one morning in 1947 and never saw Maude again. Following their 1948 divorce, Chicago gossips thought it likely he would marry Bobsy; instead he married his secretary and former student, Vesta Sutton, a pretty, younger, more compact version of his first wife.

After lingering far too long in the President’s House, Maude finally moved to Connecticut. She did realize her dream of becoming a writer, releasing several racy novels (NYRB Classics re-released her 1959 novel, Victorine, this past August). But even New Directions, Maude’s avant-garde publisher, grew tired of her fictional experiments, and the partnership fell apart. For several decades, Maude vanished from public view. She died in Bridgeport, Connecticut, on March 28, 1991, having outlived her ex-husband by 14 years. She was 91.

* * *

Photograph: Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library

|

|

|

On October 28, 1950, Elizabeth Fuller Goodspeed wed Gilbert Whipple Chapman, a wealthy New York industrialist and widower, and decamped for Manhattan and Long Island. "While happy in her happiness," wrote the Tribune, "[Chicago socialites] are wondering what one person can be found to take over all her activities." Somehow the city endured.

The public persona known as Bobsy Goodspeed did not fare so well. With her remarriage and move east, that vivid Chicago personality began to evaporate, slowly displaced by the nebulous Mrs. Gilbert W. Chapman. In 1970, the documentary filmmaker Perry Miller Adato released When This You See, Remember Me, a biography of Gertrude Stein (the film’s title was borrowed from a refrain in Four Saints). About 71 minutes into the film, a prim white-haired woman appears on screen; she is identified in a subtitle as "Mrs. Gilbert Chapman, Arts Patron." Wearing large pearl earrings as well as two strands of pearls over an unremarkable blue dress, the woman phlegmatically describes the surprising "furor of publicity" that had surrounded Stein’s 1934 arrival in the United States. There is no charm floating beneath her flat voice and certainly no mischievous light dancing in her opaque eyes.

On December 16, 1979, Gilbert Chapman died in his Manhattan home; his wife, Elizabeth, followed nine months later. She was 87. The New York Times acknowledged her death only perfunctorily; locally, the Tribune noted the passing of the onetime Chicago arts patron Elizabeth Chapman. Her first husband, Charles B. Goodspeed, warranted a brief mention, but there’s not the slightest allusion to anyone named Bobsy.

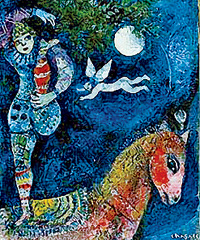

In early March 1981, a New York auction house sold off Mrs. Chapman’s artwork, jewelry, antique furniture, silver, and books. The sale netted $803,545. Of course Elizabeth Chapman had already given away several of her most important paintings. At least four of them had gone to the Art Institute of Chicago: Chagall’s The Circus Rider, Matisse’s Interior at Nice, Braque’s Still Life, and Picasso’s cubist portrait of his trailblazing art dealer, Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler. The last two gifts are dedicated to the memory of Charles Barnett Goodspeed. As for Bobsy, her most lasting memorial remains a recipe for turtle soup.

Photography: Courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago