Rod Blagojevich’s first summer in prison was, he recalls, “quite an awakening.” He had arrived at the low-security prison in Jefferson County, Colorado, about 15 miles southwest of Denver, in the spring, when there was still a mountain chill in the air. But that year, 2012, Denver experienced its hottest summer on record. From June through July, the city endured 13 days above 100 degrees. Two days reached 105, a temperature not seen in the area since 1878.

At the time, Blagojevich was housed in a dorm room with nearly 100 other inmates. The room was essentially a long, narrow hallway, partitioned into 10-man cubicles. Metal bunks lined the walls, jammed in tight. Blagojevich slept on a top bunk. “It was extremely close quarters,” he notes. With no privacy. “Just a lot of men with a lot of noise—bad sounds and bad smells.”

Blagojevich is telling me this story in an email. It is the first time since being incarcerated more than five and a half years ago that he has been interviewed.

The facility didn’t have air conditioning, either, he continues. “The heat was oppressive. Sleeping in that heat was almost impossible.” To cool down, he employed a prison trick. He emptied out the contents from the plastic bag of cereal he purchased from the commissary and filled it with ice right before evening lockdown. “I eagerly embraced that cold bag of ice to try to sleep, in much the same way you would hug a hot water bottle in the wintertime.”

Prison officials brought in several large fans and placed them around the room, but there weren’t enough to make much difference. And though the officials positioned the fans to blow in the direction of the common areas, some inmates had other ideas. “Invariably, late at night, with the lights off and only one prison guard on duty, a Hobbesian state of nature emerged,” Blagojevich says. The biggest and toughest inmates, he remembers, would turn the fans to blow toward themselves. “The combination of the oppressive heat and 100 sleep-deprived men, who happen to all be convicted felons—many in prison for crimes of violence—created a combustible situation that became a powder keg where fights occasionally broke out.”

Blagojevich sums up the experience this way: “Extreme heat, drenched in sweat, with no air movement, scores of angry men, snoring and other bad, unpleasant sounds—I remember moaning to myself, ‘How the “f” did I end up here?’ ”

For many of us, the last images we carry of Rod Blagojevich were from March 15, 2012. The sun had yet to rise when the former governor opened the door of his tan brick house in Ravenswood Manor and bounded down the front steps toward a waiting car. He was leaving for O’Hare to catch a flight to Denver to start serving his 14-year prison sentence for corruption. The most sensational of the 18 federal counts had him trying to hawk Barack Obama’s vacant Senate seat for campaign contributions or political favors. (Five of those counts were tossed on appeal in 2015, though his sentence was not reduced.) Television camera lights illuminated the black sky, and news helicopters buzzed overhead. He was immediately surrounded by a scrum of reporters, many of whom had besieged his house for days, and well-wishers who had spent the night waiting on the corner of Sunnyside Avenue.

Wearing a dark polo, a navy blazer, blue jeans, and black running shoes, Blagojevich worked his way through the crowd to the car as reporters bombarded him with questions: “Governor, what did you say to your daughters?” “Did you get any sleep last night?” “What are you thinking now?”

Not one to pass up a microphone, Blagojevich stopped and quickly addressed the crowd. “I’ll see you guys when I see ya,” he called out, then ducked into the car, which whisked him away.

Later that day, just before the noon deadline, he would surrender to authorities at the Federal Correctional Institution Englewood. Waving one last time to the news helicopters, he walked with his lawyers slowly down a long sidewalk, the tall razor-wire fencing looming just feet away. He entered the administration building and then all but vanished from the face of the earth.

Five years, two months, and eight days later, on a May afternoon, a call with a 303 area code pops up on my cell phone. My phone interview with Rod Blagojevich, Inmate 40892-424, was scheduled for 2 p.m. But it’s only 1:51. Rod Blagojevich, early? While governor, he was chronically and unapologetically late for events, if he showed up at all. He was maddeningly AWOL from Springfield and often absent, too, from his Chicago office in the Thompson Center. But here he was—early—on the other end of the line.

Weeks before, Blagojevich had agreed to an in-person visit, but officials at FCI Englewood denied the request (they said it posed a “security threat to the facility and the inmate” but didn’t elaborate). They allowed instead two telephone interviews: a 30-minute call in May (which was extended an extra 15 minutes) and an hourlong one in July.

Those conversations—as well as six lengthy emails Blagojevich sent me via his lawyer and several interviews with his wife, Patti—offer detailed glimpses into his life behind bars, his relationship with his wife and two daughters, and his thoughts on his future.

Given their history with the news media, Blagojevich and Patti were at first wary of granting the interviews. But once they did, they talked casually and candidly. The famously high-energy Blagojevich seems to have mellowed during his time in prison, though he and Patti were obviously strategic about what they chose to reveal and what stories they told. Blagojevich requested only one topic be off-limits: his criminal case. Leave that, he says, to his lawyers. He doesn’t want to antagonize any judges while his case is technically still pending; he plans to file a last-ditch appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court.

I begin our May call by noting that many people presume he’s at a “Club Fed.”

Blagojevich responds that it feels nothing like a vacation: “It’s really a prison.”

Opened in 1940, FCI Englewood sits on 320 acres in the foothills of the snowcapped Rocky Mountains next to Littleton, Colorado. The low-security facility, where Blagojevich began his sentence, houses some 920 prisoners. If it weren’t for the guards armed with assault rifles and the razor wire encircling it, one might mistake FCI Englewood for a suburban high school, albeit a rather ugly one. The concrete buildings are institutional beige, and on the grounds are ball fields, tennis courts, and a track.

In fact, across the street, to the west, is D’Evelyn Junior/Senior High School, one of Colorado’s top public schools. The east side of the prison abuts the Foothills Golf Course, a popular public links. To the south, directly across the street, are tidy residential subdivisions, with a Costco and Walmart just down the road. It’s as if a penitentiary were dropped in the center of Pleasantville.

On the same campus is the less restrictive minimum-security prison camp where Blagojevich was transferred in November 2014 and now resides, along with 170-plus other inmates.

Blagojevich asked to serve his time at FCI Englewood for several reasons. For starters, it’s one of the few federal prisons to house both low-security and minimum-security facilities. This is important because it makes it quicker and easier for inmates to transfer from one to the other once they are eligible. Second, while there are several low-security prisons much closer to Chicago, FCI Englewood’s proximity to Denver’s airport actually makes it easier for Blagojevich’s family to visit. Third, as Patti Blagojevich points out, Forbes once ranked FCI Englewood among the “12 Best Places to Go to Prison”; it is one of the least violent and least crowded federal sites. Last, but not least important for the inmate, was the inordinate number of days the sun peeks out in Colorado, which Blagojevich thought would help him stay upbeat.

Still, the long sentence has weighed heavily on him. “It’s a terrifying prospect,” he says. “I can’t lie.” He won’t be eligible for early release until he serves a little more than 12 years. The reality hit home after a couple of days at FCI Englewood, during a meeting with his case manager: “She’s going over my file with me, and she says, ‘Well, your exit day is in May of 2024.’ This is March of 2012 when she says this. It was like Joe Frazier hitting Muhammad Ali with one of those left hooks to his body, right? And then she says, ‘But I’ve got some good news for you.’ And I was able to get out, ‘What would that be?’ And she says, ‘I’m recommending six months in a halfway house.’ So I’m calculating in my mind, OK, I can be home by Christmas 2023—maybe not home, but to the halfway house.” He chuckles at the thought. He will be 68 then.

Boosting his spirits have been the “hundreds of letters” he says he’s received, most of which are supportive. Then he allows: “I occasionally get a bad one.” He tells me about a letter from a woman from Champaign. She had been working in state government in 2003 when, on Blagojevich’s first full day as governor, he fired dozens of his predecessor’s political appointees, including her. “She basically waits about 13 years to write me, and I’m in this deep, dark valley, and she says, ‘I hope you’re somebody’s you-know-what’ in prison jargon. It was kind of funny.”

Over the years, FCI Englewood has housed its fair share of high-profile inmates. In the mid-1990s, when the facility was medium-security, Oklahoma City bombers Timothy McVeigh and Terry Nichols were held there during their trials in Denver. Blagojevich has overlapped with several notorious offenders. Among them: Jeffrey Sterling, the former CIA officer who was convicted in 2015 of leaking classified information about Iran’s nuclear program to The New York Times; Jeffrey Skilling, Enron’s disgraced CEO; Rafael Cárdenas-Vela, an ex-leader of the Mexican drug-trafficking Gulf Cartel; and Jared Fogle, the former Subway pitchman convicted of distributing child pornography and having sex with minors.

For a while, Blagojevich wasn’t even the highest-level government official at FCI Englewood. Alfonso Portillo, the former president of Guatemala who pleaded guilty to laundering $2.5 million in bribes from Taiwan, spent time there before being released in 2015. Also at FCI Englewood for a spell: Mike Carona, the former sheriff of Orange County, California, who was convicted of ordering witnesses to lie during a corruption probe.

“When I first came to prison, there was a notoriety to me,” Blagojevich says. His soon-to-be fellow inmates watched his arrival live on CNN. In the cash-free economy of prison, Blagojevich’s celebrity was currency. During his first few weeks, his ID card kept getting stolen. “They thought they could sell ’em for something,” Blagojevich says. One day, he went to work out at the gym. He put his ID in his shoe but accidentally dropped it. A prisoner nicknamed Grinch found it and kept it, he says. “Grinch was part of a group of other inmates who worked at the hobby craft. They built this small piece of furniture that looked like a dresser, and they put a false floor on the bottom of the drawer and put my ID card in it so they could mail it out of the prison, ’cause [prison authorities] check all your mail.” Another inmate who was in the group but friendly with Blagojevich foiled the plan.

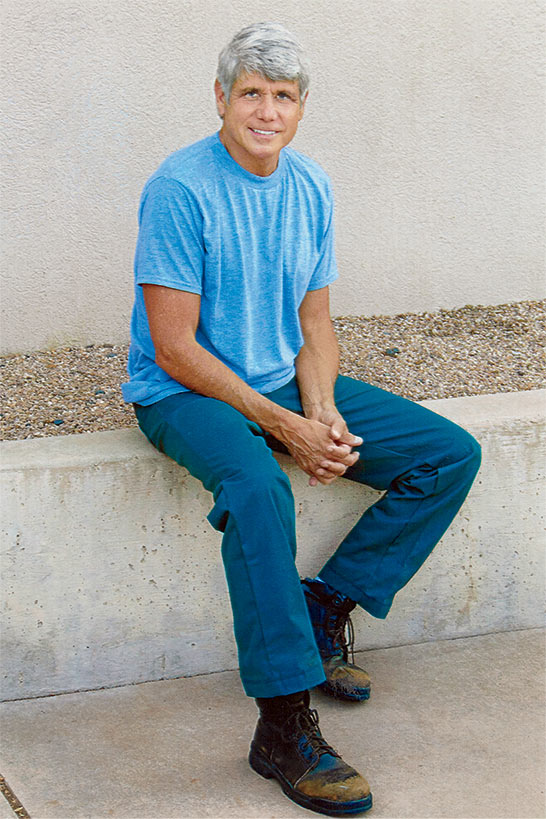

That didn’t stop others from trying to capitalize. In April 2015, the National Enquirer published several photos of Blagojevich taken by an inmate using a smuggled cell phone. The first pictures of him in FCI Englewood to surface, the fuzzy images call to mind Bigfoot sightings. In one, a bespectacled Blagojevich, with, as the Enquirer described it, “dazzling snow white” hair and dressed in a prison-issued khaki T-shirt and sweatpants with a large rip at the knee, is engrossed in a book, his chin resting on his fist and his legs up on a desk. In the other photos, he’s in track shorts and a sleeveless tee, relaxing on a bench in the sun.

Blagojevich served his initial 32 months at the low-security facility—the first 18 of them in the dorm-style room with the general prison population, until he moved into what he calls FCI Englewood’s “high-rent district,” with its two-man units the size of office cubicles. That upgrade came courtesy of an inmate Blagojevich had befriended; when the prisoner’s cellmate left FCI Englewood, he invited the ex-governor to move in. The room had a metal bunk bed and a single small window that offered a slivered glimpse of the sky and little else. “My home was a six-foot-by-12-foot prison cell, four cement walls, and a big, heavy iron door that shuts you in,” Blagojevich says.

His living situation improved greatly when he was moved to the adjoining minimum-security camp—or “outside the fence,” as the prisoners refer to the site because it has no outer barriers. Inmates with less than 10 years on their sentences and who are considered low risk for escape are eligible. “It’s night and day between ‘inside the fence’ and ‘outside the fence,’ ” Blagojevich says. “I treat this more like a training camp, actually.” He adds with a laugh: “I’m working my way back up, you know, from a deep, deep valley to a less deep valley.”

Converted from a motel that served those visiting FCI Englewood prisoners, the camp is a boomerang-shaped building with about 50 rooms. Those rooms, which sleep five, are carpeted and have bathrooms with tubs, which Blagojevich likes to use after long runs. Inmates are given much more freedom, and there is only one guard on duty each shift. “There’s lots of room for shenanigans,” says one of Blagojevich’s former cellmates, who asked not to be named. At night, after the final count, inmates have been known to venture off to Walmart to buy cigarettes. Some have even headed out to the golf course for trysts with girlfriends.

The looser vibe took Patti by surprise initially. She recalls the first time she and her daughters visited her husband at the camp. As they were driving off, they noticed Blagojevich by the side of the road, waving to them. “I was like, ‘Oh my God, this is the first time I’ve seen you outside in years,’ ” Patti recalls. “I just wanted to say, ‘Jump in the car—let’s go home!’ ”

For Blagojevich, a man who rose to political heights from modest roots (he is the son of a Serbian-born steelworker and a CTA ticket clerk), prison has been a humbling experience, full of little indignities. As at most correctional facilities, inmates are assigned menial jobs, such as washing dishes, mopping floors, and scrubbing toilets. At the low-security facility, Blagojevich did a three-month stint in the kitchen, one of the toughest tasks, but primarily worked in the law library and taught classes on the Civil War and World War II. His current job as an orderly at the camp pays $8.40 a month. “My jurisdiction was once all of the State of Illinois. Now I’ve got two hallways to clean,” he says. “I feel like I was a very good governor, and now I feel like I’m doing a pretty good job on those floors.” He recalls that his first job, at age 9, was as a shoeshine boy. “I was making more money then than I’m making as a 60-year-old former governor with a college degree and a law degree.”

In one of our phone calls, Blagojevich tells me how a correctional officer had chewed him out a few days earlier in the prison gym: “I was wearing a cutoff T-shirt, you know, like one of those muscle shirts, and he yelled at me, ‘You can’t wear that! Get out of here!’ And I said, ‘I’m in the gym.’ He said, ‘Get out of here!’ And I just walked away, but I muttered to myself, ‘Boy, if I ever get that power back …’ Then I caught myself, and I was like, ‘No, there’s no lesson in that. The guy’s doing his job.’ ”

There have been heartbreaking moments, such as during last year’s World Series. Blagojevich is a die-hard Cubs fan, and the team had long been something he and his older daughter, Amy, bonded over. So Patti bought Amy a ticket to Denver so she could watch game 3 with her dad. One problem: The correctional officer in charge that month of the camp’s cafeteria—which doubles as the visiting area—had a no-TV policy. Recalls Patti: “Rod even went to him—because I had already bought the ticket—and asked him, you know, ‘My daughter bought a ticket, she wants to watch the game with me.’ Nope! Not gonna turn the TV on.” Amy wound up staying home.

Blagojevich has come to savor the small acts of kindness. On his first day, he tells me, a group of inmates presented him with the big-house version of a welcome basket. “They took up a collection and put together a gift bag and gave me a whole bunch of different stuff that I would need before I had a chance to go to the commissary.” Among the items were coffee, a couple of plastic mugs, and a toothbrush. “It was really kind of touching. You know, these are big, tough guys, drug dealers and gangbangers and bank robbers—they have so little, right?—and it’s kind of a sweet thing that they did, welcoming you to their world.”

When Blagojevich talks about prison life, he tends to speak in the second person—“you” instead of “I”—as if he’s disassociating himself from his unpleasant reality. Which calls to mind his last public interview, in 2012, right before he was due to surrender to FCI Englewood authorities. Speaking in a restaurant in Littleton, he admitted he had been struggling to come to terms even with the word “prison.” “I think of it like a military base,” he told NBC-5’s Phil Rogers. “Like I’m reporting for military service. That’s a little game I play with myself.”

For mental and emotional fortitude behind bars, he has turned to religion. “I’ve had a chance in prison over these many years to get closer, stronger in my faith,” says Blagojevich, once an altar boy at his Serbian Orthodox church. “The lessons from the Bible and scripture have been very helpful to me. It’s strengthened my strength. It’s also strengthened my resolve. It’s convinced me further that I know what I’m doing is right. Among the lessons is, you’ve gotta put faith over fear, you gotta be willing to go through fire when you believe in something. I’ve come to see the object of life is to do God’s will. So I’m putting my trust in God and whatever his plan is for me.”

In prison, nearly everyone has a nickname. “In my housing unit alone,” Blagojevich says, “there was Smelly, Socks, Sharkey, V, Mr. B, and Boo.” Blagojevich’s nickname? Gov, naturally.

Nonetheless, he hardly runs the joint. Once a gifted glad-hander as a politician, Blagojevich is largely a loner as an inmate. “You gotta navigate carefully, you gotta deal with the politics of prison, and you gotta be careful with that,” he says, explaining why he mostly keeps to himself. “There are all kinds of reasons why, I think, it’s necessary. But it’s mostly, I think, emotional self-protection, just keeping me focused on what, I think, my purpose is.” That purpose being his own development as a person: “When I deviate from that, I find myself not as strong as I want to be.”

Blagojevich’s former cellmate tells me that at the low-security facility there was a group of white-collar offenders, the cellmate included, who would meet every Friday after lunch to talk about world events. They called themselves the White-Collar Roundtable. “We would have real deep discussions about business and politics and world financial markets, things you don’t get in prison—intellectual conversation,” he explains. But Blagojevich rarely took part. “He was usually walking the track at that time. He’d stop by, but he didn’t want to be engaged. He just didn’t want to participate. He’s fairly independent.”

Yet Blagojevich has made several close friends. At the low-security facility, one buddy was Beverly Hills real estate developer Charles Elliott Fitzgerald, whom the Los Angeles Times called the “architect of one of the largest real estate frauds in California history.” But Fitzgerald, who is serving 14 years for bilking mortgage lenders out of more than $40 million, has since been transferred to another prison. There have been other inmates Blagojevich befriended who have since been released. Says Patti: “What’s so frustrating to him is that people leave and he’s stuck there. So it’s hard to make friends because everybody’s got a shorter sentence.”

Patti tells me that while her husband has gotten close to some white-collar offenders, he’d rather socialize with other inmates. “He far prefers the honest drug dealer to the con-artist guys.”

I ask Blagojevich about that. “You gotta promise me,” he playfully implores, “you’re not going to throw on the headline ‘Blago Likes Drug Dealers.’ ” He continues: “I find myself naturally gravitating more to those guys. They come from rougher backgrounds. They didn’t really have much opportunity. I’ve found myself very sympathetic to them. There’s more of an affinity toward them. I’ve learned that there are a lot of criminals here that have good hearts. Some of these white-collar guys, boy, they tell tall tales. There are lots of victims that have been tremendously hurt and harmed by what they’ve done. Their sentences are less than guys who were wrong to deal in drugs but were like the bootleggers of my mother’s generation.”

I ask if he’s lonely.

“Well, of course, yeah,” he replies softly. “Years of loneliness and affliction, yearning for home, missing my family. But I’m OK.”

More than a week later, I receive a lengthy follow-up email from Blagojevich. He wants to elaborate. “The reason I feel this question needs a fuller answer,” he explains, “is that the separation from your family and the loneliness that ensues is central to the challenge of enduring prison, of ‘doing time.’ As anyone could probably appreciate, in prison, while you are almost always surrounded by other people and are rarely if ever alone—you are alone. All alone, except for the loneliness that never leaves you alone. It is always with you; a constant companion.”

In the email he talks about a recurring dream he had when he first got to FCI Englewood: “In the dream I was not in prison but I would be in court or in a place that represented the federal court building. That place would appear differently in each of the dreams. I dreamed I was facing criminal charges and the threat of prison. … But as that nightmare I was witnessing in my sleep was unfolding, I would invariably find comfort in telling myself something like, ‘Don’t worry, this isn’t real. It is only a dream. It won’t be long and soon I’ll wake up and can put this bad dream behind me.’ Have you ever had dreams like this where you tell yourself within the dream that you are only dreaming?”

He goes on: “The loneliness is still there today. But it’s different. The sharpness of the pain that was so intense at the beginning—where sometimes you felt you would never feel anything but that pain—has with the passing of all these years, slowly and imperceptibly aged into a sadness that has found a home inside of me. It is beneath the surface and not as intense, but it’s always with me. At the smallest prompting it can be activated. Where a moment before you might be laughing at a funny story, suddenly something happens or a thought crosses your mind and—boom!—the reality hits you. Real life intrudes.”

Like most prisons, FCI Englewood is a collection of isolated societies. “The segregation of the races and other ethnic groups is not only allowed, it’s encouraged,” Blagojevich says. Take the low-security facility’s cafeteria. The black inmates sit together. Hispanics dine in another area. White-collar prisoners have their own corner. Sex offenders are shunned by nearly everyone. “All the groups have tables of their own, and no one else from another group is allowed,” Blagojevich says.

Within his first few days, Blagojevich was summoned to the guard captain’s office for a lesson on the ins and outs of prison-yard politics. The captain and a couple of other correctional officers had found out that he’d walked the track with a black inmate. “They felt I should be made aware of the usual way things were done,” Blagojevich says. They suggested that for his protection he “ride” with a couple of other inmates in a “car” (prison slang for traveling in a clique). “The purpose is to have people who will stand behind you, should you find yourself facing a physical threat.” One of the inmates the officers recommended, Blagojevich soon discovered, was the “shot caller” of the prison’s white contingency. “Initially, to be respectful to the officers, and on their recommendation, I sought those guys out. It was then that I realized they were white supremacists and politely declined their offer of protection.”

Blagojevich tells me about one inmate he befriended at the low-security facility: Mr. B, a drug dealer from Chicago’s West Side. Tall, thin, and black, with white hair, a white mustache, and a fatherly way about him, Mr. B reminded Blagojevich of Morgan Freeman. The inmate, who was in his late 60s, was on the last leg of a 20-year sentence when the two men became close. At night, before lights out, Blagojevich would stop by Mr. B’s bunk, a few down from his. They’d talk about all kinds of things: about growing up in Chicago, about racial tensions, about the time in 1966 when Martin Luther King Jr. took up residence in North Lawndale to protest the city’s discriminatory housing practices.

One night, the two hatched a plan “in the spirit of Dr. King and his efforts to end segregation,” says Blagojevich. As a modest challenge to FCI Englewood’s racial division, Blagojevich sat with Mr. B for lunch at one of the tables designated for blacks. “At first, heads turned,” Blagojevich says. “And then—nothing. It turned out to be no big deal. No one really cared. No one complained. The days came and went, and I would sit with Mr. B every day at lunch.” They alternated between the black and white sides of the cafeteria. “We were mini civil rights activists with neither a following or a cause anyone cared about.”

While governor, Blagojevich was notoriously fanatical about following his own press. His staff would clip every story that mentioned him, and he would get irate if they missed one. These days, though, Blagojevich doesn’t much follow politics—or the news in general. “I know about the murder rate in Chicago,” he says. “I’m well aware of that. The TVs here in the common area, they’re always on. You can’t hear unless you put headphones on, but you can see the scrolling of CNN or Fox News, and when I see things about Chicago, I’ll stop and look.” He has no access to the internet. (His emails, which can go only to recipients approved by the facility, are sent through the prison’s dedicated electronic messaging system and monitored by authorities.)

He regained some interest in politics during last year’s presidential race. The 2012 campaign was another story. That October, seven months after Blagojevich arrived at FCI Englewood, the first presidential debate was held at the University of Denver, just 10 miles away. “I couldn’t watch,” he explains. “It was too painful, too close to home.” So he found a way to keep himself occupied. An inmate named Ernie, a professional musician who had gotten busted for smuggling drugs from Mexico, had been teaching Blagojevich to play the guitar. But the prison’s band room was closed that night, so they landed another spot to practice where the acoustics were good.

Here’s how Blagojevich tells it: “While Obama and Romney are debating, maybe 20 minutes from where I am, I’m in the men’s room.” The contrast was so startling it was comical, he says. “There I was in the men’s room—in prison—and the guy that I knew and was a contemporary of in politics—I was the first governor to endorse Obama for president—he’s getting ready for his second term. And when Obama got done with that debate, he was able to get on Air Force One and fly home and sleep that night in his bed in the White House. I had to go back in my bunk and spend the night in the shithouse. It was almost more amusing to me than devastating.”

As for his guitar playing, Ernie thought Blagojevich would make a better frontman. He invited the ex-governor to join his band, the Jailhouse Rockers, on vocals. Blagojevich practiced every day. “Believe it or not, you can actually improve your singing,” he says. “My two-bit cheap Elvis impersonation is less two-bit and less cheap.” The band played Elvis and Sinatra classics, as well as the blues. Their biggest gig—Blagojevich’s former cellmate remembers it as their only gig—was performing at the prison’s GED graduation ceremony in July 2013. Blagojevich recalls: “We worked five hours a day on this for months. We did six songs. The best one was the Elvis medley: all of ‘Don’t Be Cruel,’ two verses of ‘That’s All Right,’ two verses of ‘All Shook Up,’ and all of ‘Jailhouse Rock.’ ”

Blagojevich largely avoids the TV rooms, where convicts like to gather. Particularly at the low-security facility, they can be tinderboxes for fights—“so you gotta navigate carefully,” he says. “I think, in the five and a half years I’ve been here, I’ve watched maybe five movies. The Lincoln movie by Steven Spielberg, twice. I stumbled into the movie Ghost recently. It’s a nice movie, and I sat and watched it. I watch football—if the Bears play or the Dallas Cowboys play. They show the Cowboys here a lot. Of course, the Super Bowl—I try to watch that. And when the Cubs are on.” Recalls his former cellmate: “If the Dallas Cowboys were on, Rod would have a chair, front and center.”

The most productive way to spend his time, he’s found, is self-improvement. “I spend virtually every day working on things that are constructive,” he says. “It makes the passing of time a lot better. If you just wallow around and wander with no purpose, that would be almost impossible to deal with.”

Much of his day is devoted to reading, writing, and exercising. He cracks open the Bible daily. “It’s the first thing I do in the morning,” he says. “Read it. Reread it. Understand it better.” During our conversation in May, he tells me he is absorbed in Stephen Ambrose’s Undaunted Courage, about Lewis and Clark’s exploration of the Louisiana Territory, as well as Strength to Love, a collection of Martin Luther King Jr.’s sermons. He has also found solace in the Holocaust survivor Viktor Frankl’s seminal Man’s Search for Meaning, in which the author finds purpose in suffering. “I’ve read that book three times,” he says. “Inspired by it, I began to develop ideas about what I could do in the difficult circumstances I found myself in that could help me direct my energies and efforts to use the time I had to pass in prison working toward a worthy goal. Something more than just marking time and getting through the years ahead. Viktor Frankl explained it by writing if you had a ‘why’ to live, you can find the ‘how.’ ”

Most nights, Blagojevich reads until 2 or 3 o’clock, using a tiny book light he bought at the commissary. He calls the time his “Winston Churchill hours,” because Churchill did some of his best writing in the wee hours of the morning.

On and off for the past few years, Blagojevich has been doing some writing of his own: a series of inspirational essays. He describes them as stories about “different people who have faced crushing adversity and, in their own way, turned their adversity into positive achievement.” His subjects range from FDR to South Side gospel composer Thomas Dorsey, who wrote the classic “Take My Hand, Precious Lord” while grieving the deaths of his wife and infant son, and Terry Fox, the Canadian runner who lost a leg to cancer but ran halfway across that country in 1980 to raise money and awareness for cancer research. “I have written something like 12 to 15 incomplete essays so far,” says Blagojevich. “It gives me something to work on. It helps focus my thinking and puts into perspective what my family and I have had to go through.”

For Blagojevich, a longtime avid runner (recall that he was arrested and appeared in court in a blue jogging suit), exercise has taken on a new significance. “[It] has been extremely important to me, less so physically than it is mentally and emotionally. It clears your head. It gives you goals to have to work on.” His former cellmate says: “He’s always exercising. If he’s not lifting weights or running, he’s walking. He’s really superfit. He’s, like, ripped.”

Finding the right running shoes, however, has been a challenge. Almost no personal property is allowed, so Blagojevich could not bring in his preferred brand. Selection in the commissary, not surprisingly, is limited. He tried a couple of pairs until he found one he could tolerate. But when those shoes started to fall apart, he discovered the commissary had stopped stocking them. Blagojevich went around the prison looking for other inmates who had the shoes he liked in his size. He finally located someone and traded new shoes for the used pair.

But even his workouts aren’t immune from stress. Blagojevich tells me about a time he was lifting weights in the gym of the low-security facility. As he was bench-pressing, a group of “big muscle guys” stared him down. “I get done doing a set, and they’re looking at me. I didn’t know what to say. So I said, ‘I’ll never have arms as big as former governor Schwarzenegger’s, but I do believe my arms are finally bigger than former governor Palin’s.’ ” Whatever tension there was, his quip seemed to defuse it.

It’s not just his body he’s focused on improving. “I’m also working on my Spanish,” Blagojevich points out. Two of his current roommates, both from Mexico, serve as his tutors. “I did [campaign] commercials in Spanish. But now I feel like I’m a lot more conversive in it. I can say all kinds of things.”

Like what?

He thinks for a moment before rattling off a stream of Spanish.

Then he translates for me: “When the truth is on your side, you have to stand up and fight for it.”

The first time I meet up with Patti Blagojevich is at Oromo Cafe, a small coffee shop in Lincoln Square. Nobody seems to recognize her. Maybe it’s because her trademark bangs, which she wore as the state’s first lady, are now gone, her brown hair falling to her shoulders. Or perhaps it’s because she tends to shun the spotlight these days—only stepping back into it when she shows up at the federal courthouse for her husband’s hearings.

Now 52, she looks strained and tired, and her eyes are weary and sad. If you know her only as the daughter of the rough-and-tumble old-school ward boss Dick Mell or from her expletive-filled cameo on the wiretaps—egging on her husband to “hold up that fucking Cubs shit, fuck them,” referring to the alleged plot to obstruct the sale of Wrigley Field—you may be surprised that she is remarkably unassuming and, unlike her husband, reluctant to talk to reporters.

“Barbara Walters called me Foul Mouth Lady Macbeth, or something like that,” she says, a memory still fresh and painful. “Thank you, Barbara Walters.” (Actually, Walters called her a “potty mouth”; the Tribune cast her as Lady Macbeth. The New York Post dubbed her “One Nasty Blagoje-bitch.”)

Patti has stood by her husband since his arrest in December 2008, his impeachment the following month, the two trials (the first ended in a mostly hung jury and mistrial), and all the self-inflicted indignities of his wackadoodle publicity stunts, including getting fired by Donald Trump on The Celebrity Apprentice. In her husband’s absence, she has borne the burden of being the sole caretaker and provider for their two daughters, Amy, who recently turned 21, and Annie, now 14, as well as the family’s two dogs: Skittles, a Maltipoo whom Patti describes as the “sorry-your-dad’s-been-arrested dog” the family brought home around Christmas 2008, a couple of weeks after Blagojevich’s arrest, and Twix, the “sorry-your-dad-is-going-to-jail dog,” a mutt the family adopted in the months leading up to his imprisonment.

Single parenthood is “a tough row to hoe,” she says. “But I can’t indulge in feeling sorry for myself. My kids are sad and anxious, like they have PTSD. It’s been really hard for them. I can’t let myself go there. I’ve got my nervous breakdown scheduled for, like, 10 years from now, when Annie’s out of college. That’s when I can fall apart.”

During one of our calls, Blagojevich praises his wife for her poise and resolve in keeping the family functioning. “I never realized Patti was as strong as she is until all this happened.”

Patti calls “all this” her “lost decade”—beginning with the cataclysmic day that Blagojevich has referred to as the family’s Pearl Harbor, when FBI agents came knocking at their door in the predawn hours to arrest her husband. Since then, Patti has reunited with her estranged father, was investigated herself for possible illegal kickbacks, got fired from her job at a nonprofit, ate a tarantula on a reality TV show in her husband’s place, got her insurance licenses and started her own company selling coverage to business owners, and saw a number of friends desert her. “What else?” she says. “Let’s see, I’ve put on 20 pounds.”

Reconciling with her father was especially tough. Their once-close relationship was in tatters. Mell had helped her husband win two elections: to the Illinois General Assembly in 1992 and to Congress four years later. But then things soured. “My dad was making all these deals without telling Rod,” Patti says, recalling how Mell told his son-in-law whom he should hire and for what salary. “Rod said, ‘Hold on,’ and my dad was like, ‘You’re gonna do it, and I don’t want to hear anything about it.’ ”

After Blagojevich was elected governor, tensions between Mell and his protégé hit a breaking point. Blagojevich couldn’t stand that his father-in-law (sometimes dubbed the “governor-in-law”) was receiving so much credit, and Mell was furious that Blagojevich was elbowing him out of the inner circle. Patti says she and her father fought viciously. “We had, like, screaming matches. It was bad.” So bad, she recalls, that out of desperation she once anonymously called into The Dr. Laura Program radio show for advice: “I said, ‘My husband and my father are always at odds with each other, fighting, and I’m stuck in the middle here.’ Her response was ‘Don’t let yourself be put there.’ And I’m like, ‘How am I supposed to do that? Thanks for nothing.’ ”

After her husband’s arrest, she and her father began to mend their relationship, though Blagojevich and Mell’s remains frosty. (Blagojevich partially blamed Mell for his downfall; it was Mell, you might recall, who early on in his son-in-law’s governorship made the public allegations of pay-to-play politics that led to intensified scrutiny from the feds. He was sore with Blagojevich for shutting down a landfill owned by Mell’s relative.)

“My dad was really the only person who came to Rod before he left and said, ‘Don’t worry about your family—I’ll make sure they’re OK,’ ” says Patti. “That’s meaningful.” In 2011, the Blagojeviches put their Ravenswood Manor home on the market, saying they could no longer afford it. But Mell has helped the family stay put. He is also taking care of Amy’s tuition at Northwestern University, where she’s a senior. And he put Patti on his lobbying firm’s payroll to keep the books and handle filings.

His stepping in was critical for the family. They had run aground financially. Just weeks after her husband’s arrest and on the eve of his impeachment trial, Patti was fired from her six-figure job as the development director at the Chicago Christian Industrial League, a social service agency that served the homeless and has since been taken over by A Safe Haven. One reason given by her bosses, she says, was the distracting headlines—and not just her husband’s. Patti had come under intense scrutiny over the course of the federal probe, and her crass quotes from the recorded conversations with her husband were repeatedly cited in the indictment and in the media’s coverage of the scandal.

A couple of weeks after her husband’s removal from office, she was hit with a federal subpoena. Prosecutors were investigating whether Patti, who worked at the time as a real estate broker, had received hundreds of thousands of dollars for deals she had little or nothing to do with. An earlier Tribune report had found that more than three-quarters of her commissions came from clients with close political connections to or wanting to win favor from her husband. “That was scary,” recalls Patti. “That thought that they could come after both of us at the same time—that was terrifying.” Prosecutors wound up not charging Patti with any crime.

It didn’t help that certain friends suddenly avoided her “like you’ve got smallpox or something.” Patti was never the sort of see-and-be-seen socialite and political wife who attended every charity ball in town. Still, the invitations stopped coming. Which is fine by her. “I stay away from that. I don’t want to see all these politicians I can’t stand.” She did accept one recent invitation, though, from her husband’s attorney, Len Goodman, to an event held by a prochoice group. “I remember walking in at the same time as Pat Quinn,” she says. Her husband’s successor tried to give her a warm embrace, which she rebuffed. “I was like, ‘Ecch!’ ”

Her daughters have felt the impact as well. Said their dad in court: “I’ve ruined their innocence. They have to face the world knowing their father is a convicted criminal. It’s not like their name is Smith. They can’t hide.”

The girls became accidental celebrities the day their father was arrested. Amy was 12 and Annie was 5, still asleep when he was taken away in handcuffs. Their mother took them to school without telling them what had happened. “Annie was in kindergarten, so they didn’t have computers,” Patti recalls. “But Amy’s class was doing some kind of research, and it starts popping up on their screens. So I get a call from the principal saying, ‘You should probably come pick them up before, you know, it blows up here.’ ” On the car ride home, she explained the situation to them. “It was so bad,” she says, describing how the girls took the news.

They have struggled in the years since. “There’s never been some big, totally awful thing, just lots of little things,” says Patti. “Death by one thousand little cuts.” Like the classmate of Annie’s who recently made a hurtful remark about her dad in a group text Annie was on. Or the school assembly at Loyola Academy, where Amy had transferred to finish up high school. “They had a speaker from Pat Quinn’s office,” recalls Patti. “The teacher gets up there and introduces the guy, and she says, ‘He’s from the governor’s office—the one who’s not a criminal.’ Amy just sat there. Of course she was so upset. Shortly after that, they had parent-teacher conferences. Man, I hunted her down and said, ‘You owe my daughter an apology.’ It’s one thing to have it come from a kid, but a teacher?”

During our interviews, Patti receives multiple calls and texts from her daughters. They want to know where she is, if she’s OK, and when she’ll be home. After one of the texts, Patti places her cell phone on the table and frowns. “This is one of the unfortunate side effects of all this. My children are very paranoid about my safety because I’m the only one taking care of them. Even Amy is like, ‘I haven’t heard from you. You didn’t respond to my text. Let me know you’re alive.’ ”

Annie, in particular, experienced separation anxiety the first year her father was gone. “That year she missed, like, 25 days of school,” says Patti. “She didn’t want to leave me.”

Testifying at their father’s resentencing hearing last year, the girls laid bare how difficult it has been without him around. “The older I get, the harder it is to remember all of our times together,” Annie told the court. “I almost don’t want to grow up because I want to wait for him to come home.” Amy followed, saying, “I know he does his best to be there for us. But I also know that the phone calls, emails, and visits can only go so far.”

Patti talks to her husband every night, she says, usually between 9 and 10 o’clock, depending on the availability of the prison phones. The institution allots Blagojevich 300 minutes a month, and all calls, other than to his lawyer, are monitored. Patti says she looks forward to the daily chats, even if they do get monotonous. “He always wants me to tell him something hopeful. We’ve had the same conversation pretty much every night for five years.”

Visiting FCI Englewood is “physically exhausting and emotionally draining,” Patti says, and it was especially so during the two-plus years her husband was in the low-security facility. There, guests are patted down for weapons and contraband and randomly screened to make sure they aren’t carrying in drugs (their clothes are swabbed for residue). Meanwhile, Blagojevich got strip-searched before and after each visit. Recalls Patti: “He was like, ‘I’m not going through that for anybody but you guys.’ ”

Blagojevich remembers the agony and the ecstasy of the first time his family came to see him, two months after he arrived. “I looked forward to their visit with an anticipation similar to how I felt on my wedding day,” he says. “On the morning of the visit, I paid an inmate whose ‘hustle’ it was to iron prison uniforms to iron mine. It cost me four [postage] stamps.”

That same morning, Blagojevich recalls, another inmate, a drug dealer from St. Louis, approached him: “He used to see my campaign commercials before he was sent to prison. He slept in the same cubicle as me and was aware that I was waiting to be called into the visiting room.” The man, nicknamed Boo, said he had something for him and asked Blagojevich to follow him to his bunk. There, Boo discreetly pulled out a photo album from beneath his mattress. Blagojevich assumed he was going to show him family photos. “Instead, it was a collection of cologne samples he had torn out of magazines. There must have been dozens of them. He said he had been collecting them for years.” Speaking almost in a whisper, the inmate offered Blagojevich his pick of the bunch for his visit. “Cologne is not sold at the commissary,” explains Blagojevich. Boo called it the “finishing touch.”

The visiting room at that facility is a large open area with multiple rows of plastic chairs facing each other. Blagojevich would sit on one side, his wife and girls opposite him. Physical contact was limited. “You could give him a hug, a kiss hello, goodbye, you could hold hands across the aisle, but that’s it,” says Patti. Sharing food was prohibited. And in case you’re wondering, federal prisons don’t allow conjugal visits.

Visits to the camp that Blagojevich is now at are less stringent. The family sits at a four-top table in the cafeteria. They can share vending machine snacks and play cards and board games. (Even that can be irritating: Patti points out that the prison’s Scrabble set is missing multiple tiles.)

Even though visits are far more pleasant—no pat-downs or strip searches—Patti says they aren’t any less difficult emotionally. And because of this, she and the girls go less and less. The first year, Patti says, “we went, like, every five weeks.” Now they visit about four times a year. “At this point, nobody ever wants to go. There’s a real, palpable postvisit depression. It hits you in the face what you’re missing. It sends [Amy and Annie] into a tailspin when we come back.”

Not visiting as often, however, has a price, says Patti: The girls are feeling more disconnected from their father, their relationship more superficial. They don’t want to talk to him as much and feel like he’s becoming more of a stranger. “It’s kind of a Catch-22.”

Blagojevich tells me that he has felt the chasm widening with his daughters. He writes them long emails, he says, “but a lot of times they don’t read ’em.” A couple of years ago, at Christmas, he sent them a lengthy prayer he had penned for them. He was very proud of it. “I probably spent 20 hours—I spent days—it was a labor of love. I modeled the prayer on the Psalms. It was a good use of time because it helped me get through several days, actually getting some joy about it. Then I called home, and no one said anything about the prayer. I asked Patti, ‘Did they get my prayer?’ She said, ‘Yeah.’ I said, ‘What did you think of it?’ She said, ‘It was long.’ ”

I ask Patti if the strain has ever caused her to rethink their marriage. The long pause before she answers is not necessarily because she has to think about her response but because she seems taken aback by the question. “No,” she finally says. “My only explanation is, I know who he is.” He’s the same man she vowed to stick by 27 years ago, for better or for worse. “You can’t dump somebody when things get tough. I made a promise, and there’s no need to break that promise.”

She does wonder, though, what their relationship will be like when her husband is released. “We’ll have to be together because we want to be together. My relationship now—I don’t need him. I’ve been able to survive without him. I know I can exist without him.” One thing is for sure: “When Rod comes home, I never want to talk about this again.”

During the resentencing hearing last year, Blagojevich’s attorney, Len Goodman, contended that his client had become a “different man,” that his time in prison had changed him, that he was no longer “arrogant” and “angry,” and that he was a model inmate with a positive attitude. “He’s spent his time serving others,” Goodman told the court. As proof, he submitted more than 100 letters from inmates who extolled Blagojevich’s virtues as a friend, mentor, and teacher.

During that same hearing, Debra Bonamici, the assistant U.S. attorney, maintained that Blagojevich hadn’t changed at all and pointed out that he had never taken responsibility for his crimes or shown true remorse and was thus “a poor candidate for leniency.”

At his original sentencing—and at his resentencing—Blagojevich did acknowledge that he had made “mistakes” and exercised poor judgment. He apologized to the court and to the people of Illinois. But he has never admitted guilt for any of the crimes for which he was convicted.

I ask him in an email why he didn’t plead guilty and cut a deal for a lesser sentence. “I have from time to time during these many years away asked myself this question, especially when I see and hear how my daughters are hurting,” he says. “I chose to fight and not to surrender and to endure all that has come because, what other choice did I have? I firmly believe that I never crossed any lines in seeking to raise campaign contributions. … I believed I knew what the law was and that I followed it. To say otherwise, to give in to the pressure, the threat, and the fear of a long prison sentence would be to dishonor myself, setting a cowardly example for my daughters. … I have to live with the consequences of that decision. … It is a hard and unhappy experience. My life has been brought to ruin. I live in exile.”

During one of our phone calls, I ask Blagojevich whether he would do anything differently if he could. “Maybe I had too much pride,” he says. “I know I could’ve been more humble. I could’ve been less combative.”

In the past, Blagojevich was accused of having unbridled optimism that at times blinded him to inconvenient truths. That doesn’t seem to have faded. Even though he’s now down to a long-shot appeal to the Supreme Court, he is convinced that he will be vindicated: “I still believe, ultimately, we’ll prevail.”

If that attempt fails, Blagojevich’s only hope would be a presidential pardon or clemency. I point out the irony: In the six years he was governor, Blagojevich denied 93 percent of the 1,024 such requests he considered and let 2,800 pile up without action, causing a massive backlog. (By comparison, Pat Quinn acted on nearly 5,000 and granted more than one-third.) “You’re right,” Blagojevich says. “I didn’t do nearly enough. I regret that very much. I wish I knew what I know now. The sentences are extremely merciless. I’ve learned there’s a lot of oversentencing.”

I ask him if he ever envisions making a political return. He laughs, hesitant to answer. “The headline will be ‘Blago Predicts Comeback.’ ”

Then he adds that he’s read Nelson Mandela’s biography—twice. “I’m not comparing myself to Mandela by any means, but it’s inspirational to read about a guy who had to sit through prison for 27 years. Look what happened to him and his political career. I’m not making any comparison there, OK? Other than to say that through him and a lot of others, I get inspiration, and it helps to give me strength to endure.”

Patti thinks that maybe her husband could write another book or find a place on the lucrative speaker circuit: “He’s got a tale to tell that I think people would pay to hear.” But if she has anything to say about it, he won’t be back in the political arena. “When he comes home, I want to live a very quiet life,” she says. “Who knows what he wants? If he wants to get back into politics, he’ll have to do that with his second wife. No thanks.”

Unless the U.S. Supreme Court overturns his convictions, Blagojevich will almost certainly never appear on a ballot again. In fact, he’s barred from holding public office in this state; the Illinois Senate made sure of that after removing him from the governorship. Nor can he practice law, as he did before going to Springfield in 1993 as a state representative; the Illinois Supreme Court suspended his license. Blagojevich also won’t have his state pension to fall back on; the General Assembly Retirement System stripped him of that—roughly $65,000 a year—which he could have started collecting in 2011, when he reached 55. Next December, when he turns 62, he can begin collecting a federal pension, worth about $15,000 a year, for his three terms in Congress.

When I ask Blagojevich about his future, he gets uneasy. I ask him in different ways. Each time, he answers vaguely and grudgingly or changes the subject. The following is an abridged version of those responses:

“My elder daughter accuses me of being excessively optimistic, but I do believe in second acts. I do believe some of the greatest inspiration stories that help other people are those who have come back from the deepest, darkest valleys and have been able to work their way to a good place on the mountain, not necessarily on top of the mountain, but maybe way up high. I do believe that. I think of the story of David in the Bible. I’m not saying that’s me. This is David. But he had faith. And during those dark periods in the wilderness, he’s preparing, because he senses that there could be something. And he trusts in God. A lot of how I look at my time here is being in the wilderness and having the faith to not ever let them make me give up, but to prepare in my time here for what I believe could be a better day.”

As I listen to Blagojevich muse aloud about Mandela and David and other redemptive figures that he peppers the conversation with, it’s not a big leap to think he’s fantasizing about himself: being exonerated, winning an early release, being hailed as a folk hero wronged by the government—offering him a chance to revive his political career, maybe even achieve his long-held dream of one day becoming president. Whether or not he’s plotting his return, he is eager to reintroduce himself to the world: “I’m not giving up on my future.”

Comments are closed.