Oh my God, finally!” Sandra Cisneros exhales in relief. The acclaimed writer and this interviewer are experiencing technical issues on an international call. After several tries, we eventually connect. “Sometimes that happens because I’m in another country. There’s nothing we can do about that,” she says in a serene tone. The telephone line crackles and hisses for a second.

A Chicago native, Cisneros, the author of the beloved young adult novel The House on Mango Street, the historical saga Caramelo, multiple volumes of poetry, short stories, and so much more, moved to Mexico from Texas eight years ago. San Miguel de Allende, the town where she lives, not quite four hours by car northwest of Mexico City, is home to many artists.

It “just felt like Greece, and it felt like Mexico,” says Cisneros, who describes herself as a working-class Mexican American writer. “I felt happiest when I was living on an island in Greece, and [San Miguel de Allende] also reminded me of my childhood memories.”

Cisneros and her six brothers moved around Chicago a lot with her parents when she was a kid, and they also went back and forth between Chicago and Mexico Mexico City, where her grandparents lived. As an adult, Cisneros, who has received a MacArthur “genius” grant, the National Medal of Arts, and numerous other accolades, has a complicated relationship with her hometown.

“My good memories are, like, now. You know, I don’t have good memories of Chicago when I lived there,” says Cisneros, explaining she still has family here she visits often. She speaks with a hint of sadness in her voice. “It’s harder to go back, and the communities you care about are still neglected. There’s a lot of grief every time I come back to Chicago. … And I see what conditions are for Black and brown people, and it’s depressing.”

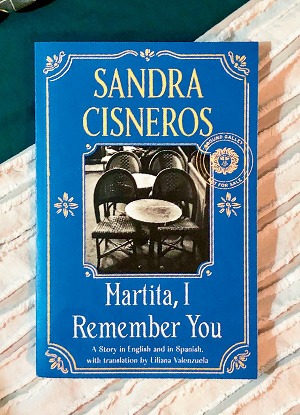

In September, Vintage published Cisneros’s new novella, Martita, I Remember You, about a Chicago woman who recalls her time as a young writer. It’s a tale Cisneros began in the early 1990s but could only finish during the past pandemic year.

“I could not write it when I was in my 30s,” Cisneros says. “I had to wait until I was older, because it’s really about a long view of a woman looking back.”

And now, at 66, Cisneros has much to consider.

“Every conversation about Chicago literature begins and ends with Sandra Cisneros,” says Donna Seaman, a Booklist editor who has known the author for more than 30 years and who interviewed her this spring at a ceremony where she was presented with a lifetime achievement award from the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame. Cisneros has a perspective “that in the original Chicago literary canon was not represented at all,” Seaman says. “She was really a new kind of radical voice when she first started.

“She’s kind of like a child of Studs Terkel, listening to the voices of people in the neighborhoods who are usually overlooked. She combines a profoundly artistic sensibility with a deeply socially conscious sense of responsibility.”

In the late 1980s, Carlos Cumpián, a poet and editor of March Abrazo Press, included Cisneros’s early work in the anthology Emergency Tacos.

“I think it’s staggeringly hard to be a pioneer,” Cumpián says. “She struck a nerve, and people wanted to hear from a Mexican American woman, a Chicago gal. She found her niche and was further empowered.

“Sandra realized how rare it is to find our literature. … Mexican Americans are a huge population, but rare to see on a national platform.”

Seaman recalls events where kids, parents, and grandparents all came to see Cisneros — “many people who themselves came from other places or were the children of immigrants. She really speaks to them. There’s just sort of an amazing connection beyond the normal enjoyment of a writer.”

Cisneros entered the literary canon in 1984 with her bestseller The House on Mango Street, which follows a 12-year-old girl growing up in a diverse, blue-collar neighborhood. The book — taught often in classrooms, banned in others — has been translated into several languages and was staged at Steppenwolf Theatre. A long-awaited TV version, set to be filmed in Chicago, is under way, and composer Derek Bermel is working on an opera adaptation.

But Cisneros calls Martita, which was just pubished in a bilingual edition, her favorite among all her writings: “I put a lot of work into it so it could be as perfect as a little jewel box.”

It began as a short story in the early 1990s, Cisneros says, but she couldn’t come up with an ending back then. “I didn’t want to abandon a good story. It was something I always treasured. I knew I would get to it when I could. You have to wait until there is some quiet in your life.”

Martita was in a “deep sleep” for 30 years, she says, before she returned to it four or five years ago. Then an excess of quiet arrived with the COVID-19 pandemic. “It was awful for most people, but it made me reassess my life, because otherwise I would’ve been out on the road.” She canceled speaking engagements so she could finally “stay still and finish this story,” she says. “I felt guilty that I could keep working and people were — and are — going through such trauma and loss and pain.”

The new work unfolds as its protagonist rereads a series of letters exchanged in her youth with two female friends, one from Buenos Aires and the other from northern Italy. Cisneros says the story “gathers the complexity” of her epic 2002 novel, Caramelo, and “the succinctness and simplicity” of The House on Mango Street.

Yet, Seaman warns, readers shouldn’t be misled by the “distilled concision.” “It’s easy to look at Sandra’s work and go, ‘Oh yeah, I get it,’ but you’re missing many dimensions. Her care with language, that observational passion she has where she just notices everything. She channels a lot into every word, as poets do.”

And while the novella is complex, Seaman adds, “her language is direct and ringing clear. It’s intense.”

But is it too direct? Cisneros says she wonders how readers here will react to the not-so-perfect portrayal of the city. “Even though it’s a picture that Chicagoans might not find flattering, I think it’s an honest portrayal.”

Her narrator, Corina, refers to Chicago as “the place I said I’d rather die than live.” It is a city inhabited by rich and poor, and not much in between. “I think it’s curious how the rich have more light and sky and lawn,” Corina says. She and her husband are fixing up a three-flat; they “got it cheap” because it’s near the expressway. “And at first you can’t sleep with all that whooshing noise, but after a while you get used to it.”

Cisneros says she learned from experience “the sounds of the buildings you can afford.”

“My uncle’s house was next to the expressway. We lived next to the train that stopped over at Hermosa Park, so our house shook with the trains,” she says. “It’s not a coincidence when you look at the city map of what communities get divided by expressways and trains. That’s true in most communities. They don’t put it in the nice, affluent neighborhoods.”

Ultimately, Cisneros says, she wanted to write about the women she met while traveling to “telescope a lot of women into three people.”

“Many of the women I know who were talented didn’t make it to become writers,” she says. “But they still have a beautiful life. … Sometimes you don’t reach your dream, but another dream reaches you.”