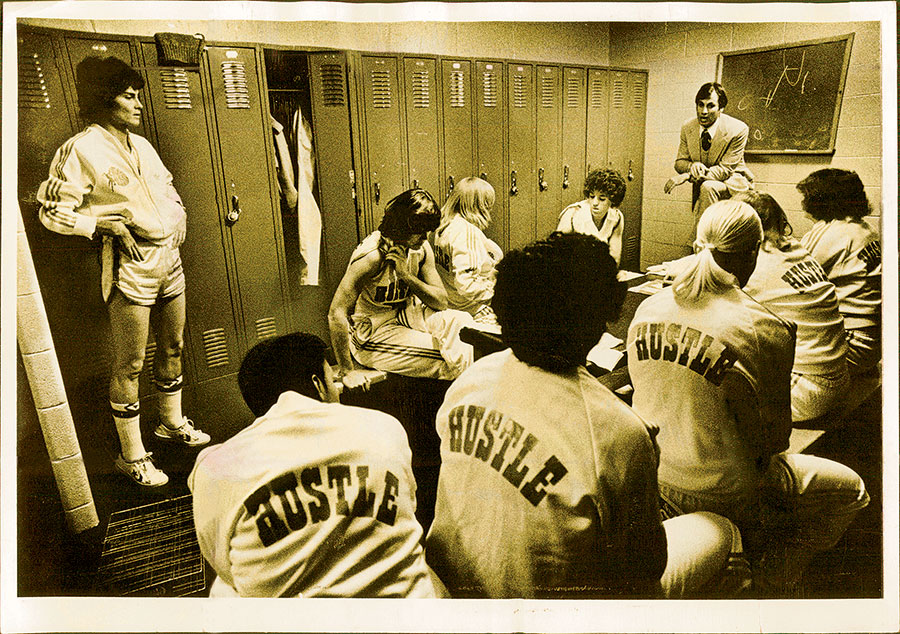

Back when the city’s professional women’s basketball team was not the Sky but rather the Chicago Hustle, the players were expected to follow a certain postgame ritual. At the end of each home contest, they would file into the locker room at DePaul’s Alumni Hall arena, clean up, then wend their way through the corridors to the Blue Demon Room, where a throng of fans awaited with drinks in hand. The opponents would often join, too, and so would begin the second half of the players’ night. Being on the Chicago Hustle meant not just playing basketball but working to ensure that the team could keep playing. And that meant putting in the social work to cultivate and maintain fans.

The Blue Demon Room was the brainchild of general manager Chuck Shriver, who kept team members busy with public appearances, signings, and outreach of all forms. It was late 1978. Title IX had taken effect but the NCAA did not yet sponsor a postseason women’s basketball tournament; the collegiate championship was administered instead by the now-defunct Association for Intercollegiate Athletics for Women. In Chicago, the Bulls were in a lull, having lost the magic of the early ’70s and still a few years from the arrival of Michael Jordan. The city’s other wintertime team, the Black Hawks, had been swept in the first round of the playoffs. There was an opening in the city’s sports landscape, and for a brief moment, a group of talented young women vied for it.

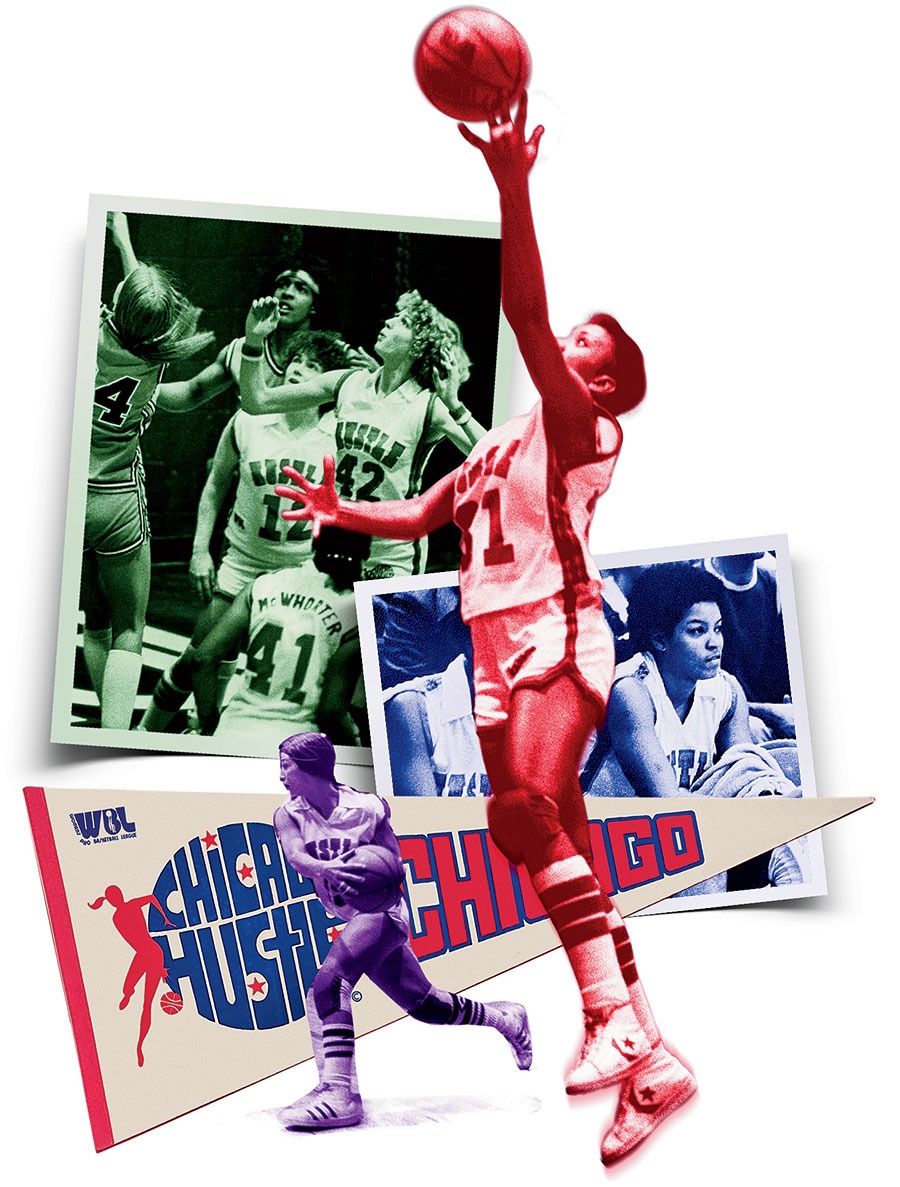

Nationally, the short-lived Women’s Professional Basketball League seemed doomed from its early stages, but in Chicago, the city’s upstart franchise flashed promise. The team led the WBL in attendance all three seasons before the league collapsed in 1981. Its inaugural game was spotlighted on the CBS Evening News with Walter Cronkite. Les Grobstein served as the play-by-play radio announcer. Nancy Faust played the organ at home games. Jerry Sloan, Walter Payton, and Reggie Theus would show up to watch the women play. Games were broadcast on WGN-TV. But even with that hoopla, there was a bootstrap aspect to the Hustle: Shriver contracted with auto mechanic students at a local community college to paint a secondhand school bus with the team’s colors and logo, serving as an in-town rolling billboard and means of transportation for visiting teams.

The whole enterprise was challenging from the beginning. As the league bore into years 2 and 3, several teams stopped paying players altogether. Franchises crumbled, players protested and left town without notice. Amid the detritus, Chicago remained standing, if only falteringly, as a viable professional option for women hoopers.

The Ford Econoline 150 came without windows or back seats. It was a cargo van. Red. Garage-band chic. Doug Bruno had acquired it to transport his players while coaching the women’s team at DePaul. He carved out some windows from the side panels and installed three bench seats in the back. A few of his players chipped in to buy their coach a cassette speaker system. When Bruno was hired as the head coach of the Hustle, he brought the van with him.

The Hustle’s first season was its best. The team finished 21–13, won the Western Division, and made the playoffs before bowing out in the first round. When the team broke for the 1979 off-season, most of the women traveled home to work and train near their families. A few stayed in the city that summer, including Debra Waddy-Rossow and Elizabeth Galloway McQuitter, best friends from Texas who had played ball together at a junior college, then at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, before signing with the Hustle and finding apartments in the same building on Winthrop Avenue on the North Side.

After a successful first season that saw Waddy-Rossow earn All-Pro honors and Galloway McQuitter lead the league in steals, the pair landed summer jobs working for the Chicago Park District. Jerry Lyne, the Loyola men’s coach at the time, worked at the park district himself in the off-season and had the idea of hiring them. There was some desk work involved, but their primary responsibility was traveling to parks around town to teach basketball. Recalls Bruno: “Jerry said, ‘Bruno, you’re in charge. You get them there, you know the city.’ ”

Bruno, then 28 with a wife and three kids, would drive the red van from his home at Cicero and Altgeld on the Northwest Side to pick up the Texas duo. It was common for other area coaches and players to tag along, so a few more pickup stops usually ensued before they’d set out for the park of the day: Kennedy Park way out on the Far Southwest Side, Washington Park near the University of Chicago, Armour Square Park by Comiskey. Or sometimes it might be the big parks like Garfield and Humboldt.

Waddy-Rossow and Galloway McQuitter had both grown up playing six-on-six half-court ball in Texas, where you were designated either an offensive or a defensive player. From UNLV on into the pros, their roles were clear-cut: Waddy-Rossow was the offensive star; Galloway McQuitter, a defensive specialist. The duo would sometimes pull local high school and college stars to help out, including future Women’s Basketball Hall of Famer Janet Harris, then a student at Marshall High.

When All-Star Charlene McWhorter Jackson signed with the Hustle, coach Bruno drove his cargo van to Milwaukee to pick her up — before she had even informed her current team.

Over the course of a clinic, a steady stream of neighborhood men would pool around the outside of the chain-link fence, sneakers on, basketballs cradled under their arms. They watched the lesson, then waited for the children to clear out. Aside from being known as part of Chicago’s women’s team, the Hustle summer park crew was building a reputation of its own: They’d take on — and dispatch — all comers.

“We probably went 45–0 that summer playing in parks all over the South Side, West Side, North Side,” remembers Bruno. “It just turned into a really fun summer. You’d start to get the drill down: Get there at maybe 10 a.m., teach the kids until 1 or so, then play against the guys for an hour, hour and a half, kick their butts, get in the van, then ride off into the sunset and stop and get some food.”

When they weren’t barnstorming, Galloway McQuitter and Waddy-Rossow would clock out from their park district shifts and take the train to the South Side to see Galloway McQuitter’s father and uncle. Alphonso Galloway, her dad, was a repairman and a building super; his brother, Carrington, owned a leather shop at 87th and Stony Island. Galloway McQuitter had been raised by her mom and stepdad in Texas, so joining the Hustle allowed her and her dad to become fixtures in each other’s lives for the first time. The Galloway brothers had a large circle of friends, who would take the young women to barbecues and parties and discos and bars. And that August, both Galloway McQuitter and Waddy-Rossow were invited to ride in the Bud Billiken Parade. They came to think of Chicago as their city, and, says Galloway McQuitter, “our fans adopted us, too.”

By the second season, 1979–80, the Blue Demon Room at Alumni Hall felt more like a party than an awkward meet-and-greet. Many of the faces were now familiar to Galloway McQuitter and Waddy-Rossow, and increasingly so to their teammates: children from the park clinics, men from the pickup games, and friends from the Galloway brothers’ circle. “I think that hands-on approach really worked,” says Galloway McQuitter. “We had our own little fan clubs, and it was because of the connection they felt with us.”

But the greater WBL was beginning to devolve into chaos. Teams were folding overnight. Following stints with two teams that each ended in missed paychecks, All-Star Charlene McWhorter Jackson signed with the Hustle in February 1980. Bruno drove to Milwaukee to pick her up — before she had even informed her current team where she was headed. “Doug had that old red van backed up to my apartment, and he came up and said, ‘Get your stuff, let’s go. You’re going to Chicago,’ ” remembers McWhorter Jackson.

Despite their new star, the Hustle disappointed that second year, posting a 17–19 record. By the time Bruno and the Texas duo departed at season’s end, it was clear that the WBL didn’t have long to go. Even Chicago, which had maintained a reputation for making its payroll, struggled that third and final year. The franchise lost roughly $300,000 both of its first two seasons, and by the third its player contracts no longer covered hospitalization or training camp expenses. In order to make rent before their first paychecks arrived in December, players were blowing through their savings, taking out loans, and offering to paint their apartments to save $100. “You know what ecstasy is?” one player asked the Chicago Tribune Magazine in 1981. “Ecstasy’s a full box of Cap’n Crunch and the milk to go with it.”

The Hustle, which eked out a winning record its final year, never won a championship or even a playoff series, but its three years of existence carried lasting resonance. The WBL helped pave the way for the start of the American Basketball League and the Women’s National Basketball Association in the 1990s. Many of the players who shaped those leagues, which crescendoed to the WNBA’s current run of popularity, grew up watching their short-lived predecessor.

After leaving the Hustle to become an assistant coach for the Loyola men’s team, Bruno came back to the women’s game in 1988, returning as DePaul’s coach. He was in the arena when the Chicago Sky claimed the 2021 WNBA title. As the Sky celebrated on the floor of Wintrust Arena, more than 40 years removed from his own coaching stint in the women’s professional ranks, Bruno cried tears of joy. “Because, to me,” he says, “it was an extension of the Chicago Hustle.”