The painting at right was the beginning of my acquaintance with Bill Savage. It was part of a show of book pictures I put up at the Rainbo Club in 2001. Selling art at a tavern is an unreliable way to make a living, but I’ve hawked my share from the walls of the Rainbo in the 15 years I’ve been privileged to exhibit there. The advantage of showing art in a bar is that patrons aren’t there to look at it and can therefore have a more honest reaction when a piece on the wall does catch their eye. The trouble with galleries and museums is that they are not “lived” places; there’s not much that goes on in them except the contemplation, collection, and commerce of the objects on display. In a bar, a picture is part of the atmosphere—the scenery—rather than a thing set apart.

A few days after the show came down in 2001, Bill called me and said he wanted to buy the painting. He then rode a bike to my place and showed up with a stack of bills. He didn’t stay long. Even then, before I knew anything about him, he always seemed like he was on his way somewhere.

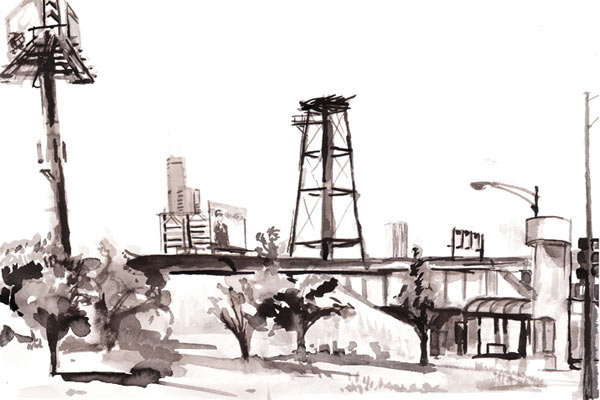

Sometime in 2007, I started driving Tony Fitzpatrick around in my cab. One of the many people I met through him was Bill. It took a little while for both of us to remember our brief meeting some six years prior. Bill had worked with Tony on several books. He got on my mailing list, and I would occasionally receive his pithy commentary in response. An ink painting called “No Tank”—of a water tower with no tank on top—caught his eye, and he bought it to complement the book painting from 2001. Water towers are a staple of old Chicago’s landscape, so it’s no wonder that a scholar of the city’s history might be drawn to a picture of one. Between that tower and the Sears Tower (that’s what it was called when I painted this, so that’ll remain its name here) in the distant background is some hundred years of local architectural toil. The connections—or lack thereof—between past and present are key to what Bill does in his own work as well.

He’s an English professor at Northwestern, leads seminars at Newberry Library, and writes articles about his neighborhood (Rogers Park), among other topics. He also tends bar at Cunneen’s on Devon. In his spare time, he bikes 3,500 to 5,000 miles a year. A dawdler he ain’t. When I signed the contract to write Hack: Stories From a Chicago Cab for University of Chicago Press and we needed to find an editor for me to work with, the answer was easier than easy. Bill was already a co-editor of the series “Chicago Visions and Revisions." From winter to spring of 2010, we’d meet up to talk over the manuscript. I’d never written a book before—or even anything longer than ten pages. Good thing Bill had. It doesn’t hurt when your editor has worked on editions of books by the likes of Algren and Hecht.

We met at various spots around town. He always arrived on his bike, which was loaded down with saddlebags, rearview mirrors, and countless other accoutrements of the dedicated, everyday cyclist. He’d take out his copy of the manuscript, marked up red in the margins with comments and corrections, and patiently explain why it was important to keep the tense of the prose consistent throughout (along with countless other rudimentary pointers for honing the work.) It didn’t hurt that my editor was an English professor. We’d talk about the book’s illustrations as well. The original contract called for 30 illustrations but we ended up with 65. Bill encouraged me to add new ones like a picture of a cat steering a woman’s car. It didn’t make it into the book, but Bill bought the original on one of my visits to Cunneen’s. There’s nothing like going to a bar and having dollars pass the other way.

I was returning to my cab from a coffee shop on Milwaukee a few months back when Bill rode up. When I asked where he was headed, he said he was a few miles short of the 5,000-mile goal for the year, so he was just riding around to reach it. There’s something to be said for creating tasks for oneself and completing them for reasons only known to ourselves. Most creative work is that way—without much apparent external reason for it—yet seeming to be inevitable and essential in retrospect. In all of Bill’s essays that I’ve read, there’s an unfussy, tough intelligence and a deadpan sort of humor. He’s not the typical uptight academic. We wouldn’t have gotten along if he were. Few people I’ve met know more about Chicago literary and cultural history than Bill, and even fewer can relate it in a way that anyone can understand and enjoy.

No novice scribbler could hope for a better guide.