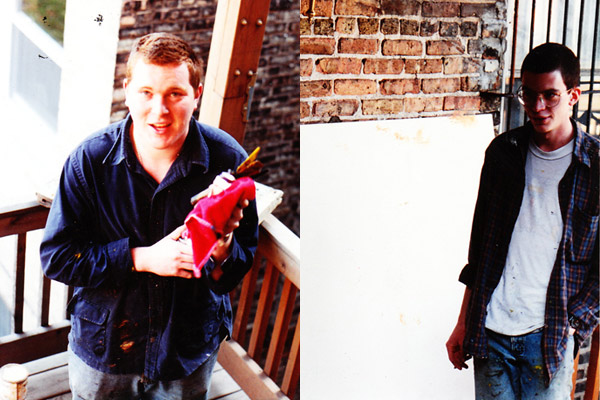

Dmitry Samarov (left) and Noah Vaughn in Logan Square, circa 1992

I met Noah Vaughn some 20 years ago. It had to be around 1990 or 1991, and it was likely in Dan Gustin’s figure-painting class at SAIC. Noah never said much, but you could tell he had a lot going on behind those watchful eyes of his. He was even less talkative than me. People, as a rule, aren’t comfortable with silence; they’ll fill the gaps any way they can. During some of the times Noah and I were around each other, there were many long, wordless stretches. But there was always a quiet understanding—or at least that’s how I felt. We didn’t need to talk. We had painting in common.

In 1991 my then-girlfriend and I, along with her brother and another couple, moved into a large four-bedroom apartment on Logan Boulevard. It had a balcony and a back porch, which was perfect for art students who wanted to paint pictures of the city. Noah, Frank Spidale, and Jun Silva, as well as a couple others, would come over fairly regularly. Everyone set up French easels, and we’d paint the alley and the backs of the neighboring apartment buildings. These were views that anyone who’s lived in Chicago for any length of time might recognize in their sleep. Their very ordinariness held much of the appeal. After painting, we’d often end up at Zacatecas on Diversey for burritos and beer. We were all interested in a kind of rough-around-the-edges style exemplified by painters like Stanley Lewis, Frank Auerbach, and Lucien Freud, to name a few. Suffice it to say that this wasn’t the most “in” genre of painting to be into at the School of the Art Institute in the early ’90s.

Noah Vaughn, "Pink Columns (Self-Portrait)"

We got our BFAs in 1993. I moved back to Boston while Noah stayed in Chicago. He went through a few jobs before landing a position with a law maintenance library service, which he holds to this day. Having a full-time job made being an observational painter difficult. The daylight hours the art required were now spent shuttling between four or five law firms downtown to update their files. Noah rented a studio and kept painting cityscapes anyway. He’d ride his bike all over the city to find views that spoke to him, make sketches on site, then try to work them up into paintings back at the studio. This method didn’t satisfy him, so he picked up a camera, thinking that snapshots might be a better source of inspiration than the sketches were. What he found out was that he hated working from photographs. But then the photographs themselves began to interest him. So eventually, they took up more and more of his time until they became his primary means of expression. It’s a lot easier to carry a camera and tripod into an abandoned building than an easel and a wet canvas—especially when you have to load it all on your bike afterwards.

Noah Vaughn, "Stickney 2010-03-29"

Noah came from Peoria, home of Caterpillar, so the industrial Midwest landscape was with him from the start. I remember a painting of his from school days that had tar mixed in with the oil paint. It was heavy, literally and figuratively, yet there was something austere and stoic to it as well; he took those qualities with him as he moved from painting to photography. I have to admit that I have a lot of problems with photography as an art form. Since its advent it’s been a mixed blessing for painters. On the one hand, it freed us from the need to “document” the world and to go as far out as imagination allows. On the other, it usurped painting’s place as our primary mode of visual communication. As someone who has spent most of his life making drawings and paintings, I’ve often found photographs wanting. The business of a snapshot freezing time has always irked me. I don’t believe our eyes, much less, our minds freeze moments. The camera lens has introduced this as a commonplace notion that now seems to be widely accepted. The ubiquity and ease of photography has encouraged a laziness in image-making as well. The thousands of years of compositional ideas introduced and refined by societies from every corner of the globe can be thrown out the window with a simple shutter click now. Access to means of expression is a double-edged sword that way: everyone can do it, which is both blessing and curse.

But the casual shutterbug can’t do what Noah does. An amateur wouldn’t risk sneaking into condemned building sites or take the time to set up a shot in a way that honors centuries of imagemaking. Another remarkable thing Noah does is to somehow avoid the “ruin porn” trap of his subject matter. A thriving industry has arisen to romanticize American urban wreckage, with Detroit being its capital. There’s something sick in glorifying decay to my way of thinking. Noah’s pictures don’t do this. I think it has to do with the often crisp, distanced compositions. He documents these crumbling, abandoned structures without making a fetish of them. And that is no small feat.

Noah Vaughn, "Dead Chairs 2009-05-01"

Much of his work is done on the South Side of Chicago, in areas that wouldn’t show up in many tourist brochures. It’s important that we see the city we live in in all its facets rather than only the brushed-clean front yard we prefer to show others. It’s also vital to find beauty in our everyday surroundings rather than the fanciful landscapes conjured by imagination or wishful thinking. These are things that Noah’s photographs do for me. When I drive by an ad for short sales tied to a chainlink fence in the middle of an abandoned lot or the remnants of what used to be a vast public-housing project, I remember some similar picture he took and in that way what I’ve seen is changed by what he saw and shared through his work. Photographs rarely do that for me. Noah’s often do, and in that way, they make me question some of my prejudices against the medium. He says he’s just trying to make a straightforward document of what he sees, but there’s an art to these unadorned pictures.

Noah Vaughn, "Sliced Melon"

Over the 20 years of our acquaintance, our paths have occasionally paralleled. We both took day jobs that were unrelated to our creative pursuits; we both kept making pictures with little or no notice from the art world; and then, in the last few years, we have suddenly received a bit of acclaim. Perhaps this was a normal, paying-your-dues process; perhaps it was a result of a stubbornness and refusal to play by others’ rules. Who knows, but the work Noah’s making now is a piece of the portrait this town will present to the world. He chose the camera while I stayed with the brush, but we both try to show people the place we live. He’s moved through spaces and places that reveal this city. His pictures are rarely peopled, but they depict the Chicago of those who live "behind the billboards, as Nelson Algren used to say.

You can see much more of Noah Vaughn's work here.