After Jovan Mosley was charged with a murder he says he didn’t commit, he spent nearly six years in Cook county jail just waiting for his day in court. His case highlights problems with our justice system

Photograph: Andreas Larsson |

|

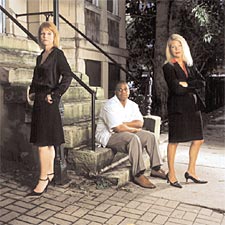

Mosley (center) with his legal team: Catharine O’Daniel (right) and Laura Caldwell (left) |

Jovan Mosley heard yelling down the hall. He looked up from the floor he was sweeping outside his cell in the “Supermax,” Cook County’s maximum-security jail at 30th and California in Chicago, and saw a blond woman who seemed anxious. Elegantly dressed and obviously a lawyer, she was waiting outside a locked visiting room while a pack of inmates yelped and whistled at her from the rec room across the hall.

“Excuse me,” Mosley said as he approached the lawyer, Catharine O’Daniel, “but if you stand over there, they won’t be able to see you.” He nodded toward a spot farther down the hall. As she moved, he positioned himself to block the wolf pack’s view, calmly sweeping.

O’Daniel thanked Mosley for his kindness and asked him about his case. His reply: nothing was happening with it. He had been behind bars awaiting trial for five long years. He had arrived when he was 19. Now he was 24. His attorney, a lawyer from the public defender’s office, had given no indication when the case might be tried.

O’Daniel was aghast. “My eyes just flew open-I found this ‘shocking to the conscience,’ to use that legal standard,” she recalls. “I liked him, and as we talked, I was struck by the fact that he was not embittered.” When she left the jail that day, O’Daniel handed her business card to a guard. “Give this to that kid,” she said.

Had it not been for his chance encounter with O’Daniel that day in December 2004, Jovan Mosley might still be waiting for his day in court. As of March of this year, there were 24 inmates in Cook County’s jail who had spent more than five years waiting to be tried, according to Paul Biebel, chief judge of the criminal division of the Circuit Court of Cook County. At least one defendant had been waiting more than seven years, and 710 had been locked up more than two.

No single culprit is to blame for this dismal record-sometimes it is in a defendant’s interest to put off going to trial; sometimes the state wants a delay. A clubby collegiality gives prosecutors and public defenders a shared interest in processing defendants through a system that was designed to be adversarial, and local judges typically do little to speed things along. The result is inertia, and the cost of maintaining it is borne by the accused, who may languish behind bars for years before answering the charges against them in court. The cost to taxpayers to support a prisoner in jail: about $23,000 per year.

“The system treated [Mosley] like he’s John Dillinger, which is crazy,” says Charles Fasano, executive director of the Prisons and Jails Program at the John Howard Association in Chicago, a prison watchdog organization. “We have guys spending more time in the county jail, awaiting trial, than they do in the state penitentiary after they get sentenced. Even if you walk [free], you’re serving a de facto sentence.”

This backlog of untried cases represents a common problem in U.S. courts, but it’s particularly egregious in Cook County, according to Ernest Friesen, a national consultant on court management. Friesen has been called to Cook County periodically since 1961 to fix-and refix-inefficiencies in the court’s administration of justice. Chronic problems plague the system, he says, because it has structural defects relating to the election of judges and the assignment of courtroom personnel. Yet Friesen optimistically regards Biebel as a catalyst, a strong leader whose experience as the Cook County public defender and as a prosecutor before becoming a judge qualifies him to understand all lawyers’ points of view. Biebel says he intends to stay in the court’s top administrative position long enough to bring significant change to a legal community he describes as “a village,” with himself as “the mayor.”

“The legal culture in Cook County is like a family,” says Friesen. “Each courtroom has a prosecutor and a public defender assigned to it, who work together all the time along with the same clerk, bailiff, and court reporter. Most of the judges are former prosecutors who came from the same court, Cook County, so they grew up in this culture. The judges want to keep the family happy, which breaks down discipline and accountability.”

For people like Mosley, caught up in this dysfunctional system, the right to a speedy trial can become a joke. Illinois’ speedy-trial law, passed in 1963, states: “Every person in custody in this State for an alleged offense shall be tried . . . within 120 days from the date he was taken into custody unless delay is occasioned by the defendant. . . .” The law puts the burden on the state-not on the defendant-to see that

justice proceeds apace. But in practice, it doesn’t work that way. Over time, custom and case law have essentially rewritten its simple language, so that judges today in Cook County customarily grant delays, or “continuances,” whenever a lawyer requests one and the other lawyers agree. Meanwhile, judges ignore the 120-day limit unless the defendant makes a written demand for trial. Even Biebel thought that Mosley should have made a written demand to exercise his speedy-trial rights. After rereading the statute and, having done so, realizing he was mistaken, Biebel said, “OK, he doesn’t have to make a demand. It’s been a while since I looked at this.”

The phrase “continued by agreement” appears a staggering 75 times on Mosley’s docket sheet. The county’s criminal judges grant so many continuances-16,000 per month in 2004, according to the county court clerk’s office-that Biebel recently hired Friesen, who founded the National Judicial College, to teach local felony judges how to manage their caseloads more efficiently.

“It isn’t that the judges aren’t working,” says Friesen. “It’s that they’re churning their cases, granting continuances. In most of the rest of the country, judges take responsibility for the pace of litigation. We need to teach the judges of Cook County that they don’t have to grant a continuance just because the lawyers agree to it.”

Jovan Mosley admits he was present during a brutal murder. After midnight on August 6, 1999, Howard Thomas, a 51-year-old grandfather, was making his way home from work at the Union League Club, where he had a job parking cars. Carrying a pair of grocery bags, he reached a house near Calumet Avenue and 73rd Street. A teenage boy and girl sat on the front porch. Mosley and four other young men stood around the steps and yard.

There are different versions of what happened next. According to contradictory police reports, three of the young men approached Thomas, and one kicked his legs to make him stumble. As he lay on the sidewalk, two or more beat him, first with their fists and then with a baseball bat, so savagely that “it sounded like gunshots,” according to a witness across the street.

Some witnesses said Mosley joined the men on the sidewalk, and they robbed Thomas of $7 and a bottle of pop. One of the witnesses, a rapper who called himself “Fettuccine Corleone,” said Mosley punched Thomas twice in the side. After the beating, Mosley walked away. He may have joined the other men walking north on Calumet as they passed around a bottle of pop-if there was a bottle of pop. Mosley now says that he never hit Thomas, never took anything from him, and there was no bottle of pop. He did not try to stop the beating, and he did not call the police. “In my neighborhood,” says Mosley, “this stuff was usual.“

Thomas died at Cook County Hospital about four hours later with three broken ribs on his left side, a cracked skull, and bones broken all over his face. The medical examiner ruled the cause of death “multiple blunt trauma injuries due to assault,” and the manner of death “homicide.”

Seven months later, Mosley, who had no previous criminal record, was arrested as he was leaving a store at 83rd and Kingston streets. Police grabbed him from behind, handcuffed him, and took him to Area Two on East 111th Street, a station infamous for allegations of police brutality in the seventies and eighties. There, says Mosley, they clipped one of the cuffs to a ring in the wall of an eight-by-eight-foot interrogation room and kept him there for more than 29 hours. Throughout the night and all of the next day, two detectives questioned him. “I was scared at first,” Mosley says, “and then I was tired. I kept telling them I did not touch that man. They’d say, ‘You did it-we know you did.’ I was in that little room for two days without anything to eat, no trips to the bathroom, no water.”

Andrew Varga, the assistant state’s attorney who supervised the case, disputes Mosley’s account of the interrogation. “In my opinion, it is unlikely this happened,” he says. “The detectives denied mistreatment at a hearing, and the judge denied Mosley’s motion to suppress the statement.” But Varga does not dispute a point O’Daniel raised at Mosley’s trial-that Mosley’s file contained no general progress reports of the interrogation, the journal-like notes that detectives routinely write to document the treatment and response of subjects.

Mosley says the police pressed him to admit he had punched the victim. “They said they didn’t want me-they wanted the guy with the bat,” he recalls. “A couple of punches aren’t murder. They told me if I admitted I hit the man two times on the side, they’d let me go home.” After Mosley said he would sign a confession, an officer called an assistant state’s attorney to come in and draft the statement. “Then the officer brought me these big, thick sandwiches,” Mosley says. Exhausted and expecting to go home, Mosley signed the handwritten document. (Too late for Mosley, Illinois law has required since July 2003 the videotaping of all homicide interrogations.)

Mosley thought that signing the confession for a seemingly minor offense was a way out of his ordeal. As he looks back on it now, though, he says, “They tricked me.” The law of accountability in Illinois means that by admitting he hit Thomas, Mosley could be charged with murder. As O’Daniel puts it, “If you’re in for a penny, you’re in for a pound.”

Mosley was charged with first-degree murder and armed robbery. A judge set his bond at $1.5 million, well beyond the means of Mosley’s family. (His parents were unemployed; one brother was in prison, and his other brother had died several years earlier of complications from AIDS.) Mosley joined the general population deck at Cook County Jail Division 11, the Supermax, where he saw frequent fights and a brutal stabbing. To protect himself, he became a regular in the rec room, crunching weights when the machines worked and lifting plastic bags of water when they didn’t. He shed 20 pounds from his five-foot ten-inch frame and turned much of the remaining 220 pounds into muscle.

“I have this baby face, right?” he says. “But I also have a look that scares people. I wore tank tops to show everybody what I had. They left me alone. I was never raped. There were people getting raped, though. It happened in the cells, not in the open, and the rapists were the guys who had been in and out of the penitentiary their whole lives.”

In the Supermax, the two-person cells don’t have bars. They slam shut with metal doors pierced by narrow crossbow slits. After a few months, Mosley was granted a transfer to the Life Learning-or “Christian”-deck. There he performed Gospel rap, led Bible studies, and resolved disputes for his fellow inmates. Many of the guards befriended him and even looked the other way while he cooked in his cell. He even became famous for his apple pie, which he cooked on the metal table in his cell over a fire fueled by empty milk cartons. (Visit Chicagomag.com for Jovan Mosley’s apple pie recipe.)

But nothing was happening with his case. Mosley went to court once a month with his public defender, Edwin H. Korb, who agreed to dozens of continuances but filed only one paper, a motion to quash arrest and suppress evidence. Korb didn’t push Mosley’s case, he explains, because there was a 15-year-old eyewitness, and he wanted to wait to interview her until she turned 17 and became emancipated from her father, a police officer. Also, Mosley’s was a multiple-defendant case, the kind in which time can work to the client’s advantage.

“If you demand trial,” says Korb, “you aim the spotlight at your client. State’s attorneys hate trial demands, so they’ll focus everything they have on your guy. They’re under pressure from the victim’s family, who are understandably very angry. If you wait, that heat begins to dissipate.”

Heat of another kind flares up when defense attorneys demand trial, says Locke Bowman, legal director of the MacArthur Justice Center of the University of Chicago. “When it happens, the air in the courtroom crackles,” he says. “In the culture of 26th and California, it’s perceived as rudeness or effrontery for a defense lawyer to demand trial. The defense is forcing the state’s attorney to turn his or her attention to the case, and in this very inbred culture, that will be remembered.”

In 2002, some 18 months after taking Mosley’s case, Korb took early retirement and ran for judge of the circuit court, legally changing his name to the Irish-sounding Edward K. Flanagan to increase his chances of winning. The ruse didn’t work. After losing the election, he took back the name Korb and opened up a solo law practice.

Mosley’s case went to James Fryman, another public defender in the multiple-defendant division. For the next three years, Fryman agreed to monthly continuances. Sometimes there were legitimate reasons for delay: twice, the case was assigned to another judge, and the original prosecutor got sick and eventually died. But most of the delays were granted for no compelling reason, with no explanation appearing in the record about the nature of the request or the name of the party making it.

Mosley waited longer than most defendants, says Fryman, because it’s difficult to get four defendants, their lawyers, and witnesses together in the same courtroom at the same time. During the pretrial phase, while the court considered motions to suppress evidence, the four cases were kept together. Eventually they were tried in pairs, a year apart, according to the order in which the motions had been decided.

Cook County public defender Edwin Burnette explains that delay can also be used strategically, especially in a multiple-defendant case like Mosley’s. In such a case, “nobody wants to go first,” says Burnette. “Being able to observe individuals who testify at the earlier trials gives a tactical advantage to individuals who are tried later.”

What’s a defendant to do? Because Mosley was not representing himself, his lawyers spoke for him. “How does he make a speedy-trial demand if his lawyer won’t do it for him?” asks Biebel. “I don’t know. Good question.”

Plea bargaining begins to look attractive after years in jail, so inmates may admit to things they didn’t do simply to end the suspense and avoid the risk of going to trial. A vast majority of Cook County’s felony cases, 86 percent, are disposed of by plea bargains. This is not an unusually high percentage, according to Friesen, but Cook County does have what he calls “undoubtedly the lowest rate of jury trials in the country.” That is offset by a relatively high rate of bench trials, but defendants who exercise their constitutional right to a jury trial must wait.

Those defendants who do ask for a jury trial risk a particularly severe sentence. “When you think of the right to a jury trial,” says Korb, “don’t forget the ‘jury tax.’ The judge will never say on the record, ‘You went to trial, so you’ll get your butt kicked’-that would be grounds for appeal-but if your client is found guilty, you can bet he won’t get the minimum. The common wisdom is that it adds more than 20 years to time for murder.”

The state’s attorney’s office would like to see the number of trials increase, according to Robert Milan, first assistant state’s attorney for Cook County. “This wasn’t a case that fell through the cracks,” he says about Mosley’s. “It was just one that came in prior to what we’re doing now.”

The pressure exerted on defendants to plea-bargain may come not from the prosecutor but from their own lawyers. “If you have a bad case,” says James Mullenix, a 24-year veteran of the public defender’s office who represented one of Mosley’s codefendants, “you need time to work on your guy. You try to convince him that pleading guilty is the best thing to do.”

Sometimes even defense lawyers find it hard to believe their own clients are not guilty. “The system functions with a pristine, paper presumption of innocence, but an in-practice assumption that everybody’s guilty,” says Bowman. “If you practice in the criminal area, you get accustomed to knowing that the person you are representing will probably be convicted at trial. You have no incentive to demand trial if you think you’re going to lose.” (All of Mosley’s codefendants were tried, one by a judge and two by juries. They were found guilty and sentenced to 32, 43, and 55 years, respectively, the longer sentences imposed-by the juries-on the two men who had used the bat.)

Fryman thought Mosley had a bad case, that the odds were 60 to 40 against him. When the state offered Mosley 18 years to plead guilty to armed robbery, Fryman urged him to consider it. “He had signed a confession,” Fryman says. “He was the state’s star witness against himself. The pictures of the victim were grotesque, like a special-effects movie. I told Jovan, when the jury saw those he’d be looking at a 30- or 40-year sentence.”

Mosley still refused to plead. “I was getting mad,” Mosley remembers. “Finally I lost it and asked Fryman, ‘Who is this state’s attorney? Is he better than you? Can you beat him?’ He was convinced I was guilty of something.”

Mosley may have been right about that. “He was a nice kid, quiet and polite,” Fryman says. “But I always thought there was something slick about him.”

A few days after meeting Mosley at the jail, Catharine O’Daniel got a phone call from his mother, Dolores, asking for help. O’Daniel knew Mosley’s family couldn’t afford to pay her, but she took the case anyway. “I liked him, and I hated the fact that the legal system had passed him by,” she says. “I called my sister and said, ‘What kind of person am I if I won’t help anyone except for money?’ I’d never taken a pro bono case before, but I’d never met a kid like Jovan before.”

O’Daniel, who worked her way through John Marshall Law School and was admitted to the Illinois bar in 1993, replaced Fryman on the case in the early part of 2005. She delved into the police and coroner’s reports, interviewed witnesses, and prepared for trial. She estimates her total time on the case to have been worth $100,000.

Trial began on November 9th of last year for both Mosley and one of his codefendants, in the same courtroom but with different juries. O’Daniel asked a friend, the lawyer and novelist Laura Caldwell, to assist at the trial. “I hadn’t tried a parking ticket before, let alone a murder,” says Caldwell, “but Jovan was such a kind, smart kid. Even if he had done the worst things anyone said he did, should he spend 25 years, or even six, in jail for two punches and a sip of pop?”

On the first day of the trial, Mosley, wearing a suit his mother had bought for him, took his seat at the defense table. He felt a wave of fear and nausea as the first group of potential jurors filed into the courtroom. “That made it real,” he says. “These were the people who were going to decide the rest of my life.” He and O’Daniel, along with the prosecutors, selected five men and seven women for the jury. Andrea Schultz, a retired phone-company manager, became the foreman.

The jury heard testimony by police detectives, eyewitnesses, the medical examiner, and a woman who had supervised Mosley’s work in a law office during the year he graduated from high school.

“I’m a conservative person,” says Schultz. “I generally side with law enforcement and believe they do everything right, so I worried about releasing another criminal. But Jovan’s demeanor was incredibly respectful. The hardest thing for most of us was the confession. But there was a young black man on the jury, Alfonzo Lewis, who helped us understand that. He asked us how many times had someone put a paper in front of us and said, Sign! Did we always read it? No. We tended to believe what we were told about it. That made us realize the same thing could have happened to Jovan.”

Significantly, Fettuccine Corleone-who had told police Mosley punched the victim-was not called to testify. “When we spoke to him a few weeks before trial,” says Andrew Varga, the assistant state’s attorney, “he told us the things he had written were things he heard on the street, not things he had seen Jovan do. He said he also was drunk that night.”

After four days, acting on O’Daniel’s advice, Mosley decided not to testify. The evidentiary phase of the trial ended. A deputy escorted Mosley behind the courtroom to the bullpen that holds prisoners during court appearances, to wait for his bus ride to jail. O’Daniel went back to see him. “I told him, ‘This is it, buddy. Tomorrow we’re going to get our answer,'” she says. “I intended to give him a pep talk. I was going to say, ‘No matter what happens, I’m so glad I met you.’ But I couldn’t say it. He teared up. I saw his big, puppy eyes, and then I teared up, too. We were standing there holding each other through the bars. We just stood there and cried.”

When she left the building, O’Daniel got into her car and called her mother. “If I lose this trial,” she said, “it will break my heart.” She couldn’t sleep, but she hadn’t been able to sleep all week.

The following morning, O’Daniel delivered her closing argument to the jury. She emphasized that none of the state’s witnesses had testified that Mosley hit Thomas. She pointed out that police were required to write up reports on interrogations, yet they had failed to produce any documentation detailing Mosley’s 29 hours of questioning.

After prosecutors Ethan Holland and James Lynch made their closing arguments, the jurors retired to deliberate. Four hours later, they returned to the courtroom and announced that they had reached a verdict. The defendant was asked to rise. O’Daniel and Caldwell each took an arm and braced Mosley as he stood between them. Mosley was shaking.

“We, the jury,” read the clerk, “find the defendant not guilty of armed robbery.” Tears began to run down Mosley’s cheeks-but then he realized he still faced the more serious charge. It felt like an hour before the clerk spoke again. He couldn’t wipe his face, because his lawyers wouldn’t let go of his arms. “I could hardly breathe because I was so nervous, and I could hardly move because I was being smashed,” he says, recalling how his lawyers nervously squeezed his arms.

“We, the jury,” the clerk announced, “find the defendant not guilty of murder.”

Mosley collapsed into a huddle with O’Daniel and Caldwell. At 4:25 p.m. on November 17, 2005, the tension of the trial and the angst of nearly six years in jail began to dissipate. Laughing, crying, Mosley looked up to find his mother’s face in the courtroom.

Months later, Mosley is sitting in a Loop coffee shop, smiling across a table at O’Daniel. In January he had enrolled at Richard J. Daley College and was recently invited to join the honors program. Working in a law firm, living in the home of his godmother, he says he feels no desire to return to his old neighborhood or to see his old friends. He has filed a civil suit against police officers involved in his interrogation.

He puts his palms together, folding his hands over his broad nose. A quiet smile lights his face. “You want to know how it feels to be out?” Mosley says. “Not the way I expected. I thought I’d be mad, but I’m not, at least so far. That first night, when I walked out of jail and got to California Street, I thought, wait, you’re supposed to look both ways. That street was huge. I felt like a midget in the big world.

“I still can’t get used to certain things. I wake up at 3:30 in the morning, like they made us do in jail. It feels strange to see so many people going wherever they want. I’m always looking around, watching everybody. In some ways, I feel very young. I went in a teenager, and now I’m 26. I feel like I missed some formative years. In other ways, I’m old, because I am patient.” He blows air between his folded palms. “Yes, am I patient.”