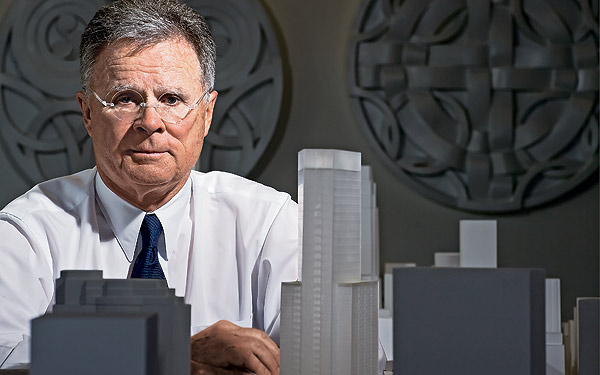

The architect Laurence Booth in his West Loop office with a model (right) for his proposed Evanston high-rise

If architects have their own version of hell, it probably resembles the community meeting that Laurence Booth, a principal of the architecture firm Booth Hansen, attended earlier this year in Evanston. One evening last spring, a hundred or so residents lined up to debate the pros and cons of one of the largest commissions of his career. The previous day, Blair Kamin, the Chicago Tribune's architecture critic, had published an item on his blog criticizing the project—a 38-story skyscraper on a prominent downtown block—for what he termed its "squat" and "uninspiring" proportions.

Meetings of this kind have their own dynamic, starting with the fact that supporters of the buildings rarely bother to attend. The result is that aggrieved opponents tend to dominate the podium. As the evening wore on, the residents criticized every aspect of the project—the aesthetics, the financing, the parking arrangements, "the way it will change downtown Evanston forever."

"No one feels a need for this tower," said one woman. "This project should never be approved," said another person. "Let the people of this city decide what their downtown is going to look like," said a third.

Booth, 72, a slight, energetic man in a tailored navy-blue suit and clear plastic glasses, stood up a little wanly at the end. "I don't know what just happened here tonight," he said. Then, referring to the project, he added, "I guess it's a wounded duck at this point."

Not yet. As of presstime, the tower was still under discussion and may eventually be built. But the experience highlights the odd crossroads at which Booth, one of the city's most respected architects, now finds himself. After more than 40 years as a premier designer of single-family houses, schools, churches, and low-rise commercial buildings, he is pursuing what for many years he insisted he never would: the high-stakes world of downtown skyscrapers.

In the late 1970s, Booth was a founding member of the Chicago Seven, a group of rowdy young architects who helped usher in the postmodern era with a series of groundbreaking exhibitions and manifestoes that questioned—and occasionally ridiculed—the received orthodoxies of the International style. At the time, Booth opposed all high-rises, calling them "antihuman" and the "product of greed and hubris and technology."

And now? "My feelings have changed," he says.

Since the beginning of the decade, Booth has designed three residential high-rises, with a fourth currently under construction just south of the intersection of North and Clybourn avenues. The Evanston project, if approved, will be his fifth. And two years ago, Booth supervised the renovation of the 37-story art deco Palmolive Building on North Michigan Avenue into a luxury condominium.

The clear winner, at least among the completed buildings, is 30 West Oak Street, a 24-story condominium tower with an elegant curved-glass façade. The building recently was named the best new building of 2007 by the Friends of Downtown, an activist group. Indeed, the success of 30 West Oak was a major factor in Booth's selection for the Evanston project. "We really liked what he did there and thought it was the kind of image we'd like to create in Evanston," says Tim Anderson, the developer.

Reactions to Booth's other high-rise buildings have been mixed. The most recent, a 31-story multiuse project at the corner of State and Randolph streets, is anchored by the headquarters of the Joffrey Ballet. Known as MoMo (short for Modern Momentum), the building garnered faint praise from Blair Kamin, who labeled it a "strong but decidedly imperfect work of architecture." Typically self-deprecating, Booth says, "I don't think we've built any really obnoxious high-rises yet."

* * *

The question for many, though, is why Booth is building any high-rises at all. "It's about the main chance," says Stanley Tigerman, a principal in the architecture firm Tigerman McCurry and Booth's first employer in the 1960s. Tigerman also drafted Booth into the Chicago Seven, and the two have been friends for more than 40 years. "Larry wants a piece of the big action."

"He's got a big office to support," says Ben Weese, a fellow member of the Chicago Seven and another longtime friend.

Booth, however, insists that there is more to it than that. "We have to make some huge changes in this country," he says. "This has been gnawing at me for a long time. The United States accounts for five percent of the world's population and uses 30 percent of the world's resources. It's not sustainable." The key, he believes, is rethinking development patterns. "In order to have a Jewel or a Starbucks within walking distance of your house," he says, "you need density, you need—in a word— high-rises."

The second reason is more personal. Over the years, Booth and his family—his wife, Pat, and their four children, now grown—have led a fairly peripatetic existence. By Booth's count, they have lived in six houses or apartments, including a row house on West Fullerton Parkway and a townhouse in Dearborn Park. But three years ago, the couple moved into an apartment on the 15th floor of the Palmolive Building. "I had never lived in a high-rise, and I thought it was time to try it out," Booth says. "Actually, it's amazingly comfortable."

This almost casual reversal of a long-held belief is highly characteristic of Booth. In fact, it defines his personality as an architect. "I'll try anything," he admits. "Some architects, they're into style, and you know what you're going to get. I'm not a stylist. I'm free. I'm looking for freedom." Then, in one of those stream-of-consciousness remarks that are a leitmotif of his conversation, he adds, "Frank Gehry has this thing in his head that he wants to get out there. I don't. Life is a treasure hunt. It's not a crusade. I want to be surprised."

That is evident in Booth's buildings, which cover a broad stylistic range from traditional to modern and beyond. About the only thing that ties them all together is a certain precision and economy in terms of forms and proportions. The adjectives that come to mind are words like "neat" and "trim." Nothing looks overdone.

"Larry does very solid, quietly elegant buildings," says Michael Tobin, a developer who worked with Booth on the restoration of the Hampton Majestic hotel above the Shubert—now the Bank of America—Theater. "They're not flashy. There's nothing you can point to and say, ‘That looks like a Larry Booth building.' But they have a sort of joy of life about them that is rare in architecture."

"He remains vulnerable to circumstance," says Tigerman. "He's not sufficiently dogmatic to have one overarching way of doing things."

Until now, Booth has had one of the more satisfying career arcs in Chicago architecture. The only child of a patent attorney and a housewife, he grew up in suburban La Grange and graduated from Stanford University in 1958. He went on to do graduate work at both Harvard and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. When he was 24, he married Pat, whom he had met in high school, and they spent a year traveling through Europe. In Athens, Booth happened to meet Walter Netsch, then at the beginning of his celebrated career as a designer for Skidmore, Owings & Merrill in Chicago. Months later, Netsch steered him to Stanley Tigerman's then fledgling firm.

"Larry had very defined opinions," Tigerman recalls, "and he drew almost like Korean nuns might weave sweaters underwater—tiny little drawings that were very precise and compelling."

James Nagle, a Stanford acquaintance of Booth's, also worked for Tigerman. Eventually, the two decided to go out on their own. Over the next 20 years, the firm of Booth & Nagle became a major player in the burgeoning Lincoln Park renovation scene. Booth traces his interest in historic architecture, and in particular the work of such 19th-century Chicago masters as Louis Sullivan and John Wellborn Root, to the dozens of vintage structures he restored and renovated in those years. "I'm not uncomfortable with history," Booth says. "You deal with those old buildings on a daily basis and you realize they're beautifully made. They work."

The architecture world is informally divided into residential and everything else, with the latter tending to overshadow the former. Frank Lloyd Wright notwithstanding, architects rarely become household names on the basis of their residential work. Booth is one of the exceptions. Over the years, he has done it all—everything from public housing to yuppie loft conversions to Gold Coast and North Shore mansions—and has been acclaimed for both his craftsmanship and his stylistic virtuosity.

"Houses are a lot of fun," Booth says. "Commercial projects tend to be more about problem solving. But housing is about individual clients and their wants and needs. You wind up getting to know people very well. Some become friends. There's a lot of satisfaction there."

Photograph: Nathan Kirkman

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Booth's first house, designed in 1967, was a modernist glass-and-brick box in Hyde Park. Since then, he has evolved into a generalist. "Now it's all about how things feel, what's the actual human experience of walking into a space," he says. "Because one of the things I think has gone wrong with architecture is that rationality has trumped feeling. Solving functional problems is relatively easy. The challenge is the emotional part."

During this period, Booth became friends with the late Harry Weese, one of the most protean architects Chicago has produced. "Harry could intuit where things were going," Booth says. "He understood the unseen forces and people that shaped the city."

"[Harry and Larry] both had a very freewheeling, let's-do-it-and-the-devil-take-the-hindmost kind of attitude," says Ben Weese, Harry's brother.

Over the years, Booth and Harry Weese collaborated on a number of projects, most notably the redevelopment of Printers Row in the late 1980s into the city's first loft district. This, in turn, jump-started the redevelopment of the South Loop, where Booth also played a leading role by designing and developing the 200-plus townhouses that constitute the first phase of Dearborn Park.

Booth's other defining influence was the Chicago Seven, a classic case of Young Turks storming the citadel of the Establishment. In addition to Booth, Tigerman, and Weese, the Seven consisted of the architects Thomas Beeby, Stuart Cohen, James Freed, and James Nagle. The Seven—and the principles they championed—are generally remembered as the last time the city was at the center of a national architectural movement.

"Chicago's importance to the world of architecture has always been as much about ideas as about buildings," says Tim Samuelson, the city's cultural historian. "That's what the Chicago Seven were about."

"We wanted a place at the table," says Tigerman, who by most accounts was the main organizer of the group. "Chicago was very tightly held in those years. The Miesian succession held sway. The Seven didn't have a replacement for that dogma, but we wanted to open a dialogue. And we accomplished that."

"We kind of pulled the thread that helped untangle the Mies cult," says Booth. The irony is that today, Booth and his remaining Chicago Seven colleagues—James Freed died in 2005—are integral members of that selfsame establishment. And Booth is even having second thoughts about Mies. "It's important to have Mies around," he says. "He's like a rock, a lighthouse in the middle of a storm. He's so elegant and reductive."

(But only up to a point. Several years ago, Booth and his wife attended a charitable auction at which they won the opportunity to spend a night at Mies's Farnsworth House in Plano. "I remember one of my daughters and her husband and son came out for dinner and brought bags of Kentucky Fried Chicken, which is a normal, perfectly legitimate thing to do," Booth says. "But it doesn't really work there. It's a cocktail-party house. That's all you can do there. Anything else violates it.")

In 1978, Booth and Nagle were joined by Jack Hartray, and the name of the firm was changed to Booth, Nagle & Hartray. Two years later, however, the partnership broke up and the three agreed to go their separate ways. Shortly afterward, Booth started a new firm with Paul Hansen, who oversaw business operations while Booth continued focusing on design. That relationship lasted until the early 1990s, when Hansen temporarily retired from architecture to explore an online opportunity. (He has since returned to the profession and now works for VOA Associates, another Chicago firm.) In the aftermath, Booth decided to retain the firm's name—Booth Hansen Architects—in part because his wife's maiden name is Hansen.

Today, Booth has three partners—George Halik, Charlie Stetson, and Sandy Stevenson—but he remains the firm's chief of design. The practice also has about 45 design associates and other employees. "It's a wide-open office," Ste- venson says of the firm's headquarters in a vintage loft building in the West Loop. "Larry sits out in the middle of the floor. There aren't too many offices with doors here." Indeed, in a sea of desks, the only objects that distinguish Booth's workspace are two neo-baroque table lamps by the Italian designer Ferruccio Laviani.

Booth reached a turning point in the late 1990s with a project that allowed him to restore and complete one of the city's most important historic structures. That building, Old St. Patrick's in the West Loop, is the city's oldest church and one of a handful of properties to have survived the Chicago Fire. Old St. Patrick's was completed in 1856 to house Chicago's growing West Side Irish community. The problem was that the church never had enough money to finish the interior.

Early in the 20th century, a Chicago artist named Thomas O'Shaughnessy had added some decorative stenciling to the sanctuary as well as a series of magnificent stained-glass windows. Both the stencils and the windows incorporated motifs from the Book of Kells, an eighth-century illuminated manuscript detailing the life of Christ and a key document in the evolution of the Irish Catholic Church.

Old St. Patrick's started declining in the 1950s, and by the early 1980s the congregation was down to only four members. By then, the stencils had been painted over, and the church was in shambles. But a few years later, a remarkable resurgence began when Father Jack Wall was named the pastor. By the late 1990s, Old St. Patrick's was one of the fastest-growing churches in the diocese, with a congregation that included Booth and his family, as well as notables such as Mayor Daley and his wife, Maggie. At that point, Father Wall decided that a restoration was needed and asked Booth to propose alternatives. Old St. Pat's represented that rarest of opportunities for an architect in less-is-more Chicago: a chance to create an explosion of color and ornament.

"Thinking about it," Booth says, "it became clear to me that the last thing you wanted to do was clear everything out, paint it white, and make it modern." He did the opposite. "We started where O'Shaughnessy left off."

The highlight is a spectacular two-story altar screen executed by Booth in white plaster that incorporates motifs from the Creation story, beginning with plants, fish, and animals and ending with the Trinity. "It has content" is the way Booth dryly describes it.

"There's a deep humility on Larry's part to honor both O'Shaughnessy and the Book of Kells," says Father Wall. "It's a restoration and then a completion of the task of creating a space that totally reflects the Celtic worldview. It's very organic and expresses the interconnectedness of nature and man. It's very powerful and very modern."

More than just about any project Booth has completed, it also sums up his approach to architecture. "It's not functional," Booth says. "It's about the poetics of architecture and human life. But it starts with the people who are going to use the building. You find what's important and what's real and then you build on that."

Photography: (Image 1) Wayne Cable; (Image 2) Courtesy of Booth Hansen Architects; (Images 3 and 5) Michelle Litvin; (Image 4) Chicago Tribune; (Image 6) Courtesy of Booth Hansen Architects

A rendering of the building for downtown Evanston

A rendering of the building for downtown Evanston MoMo, a multiuse project in the Loop

MoMo, a multiuse project in the Loop

An exterior view of the Palmolive

An exterior view of the Palmolive The restored Old St. Patrick's in the West Loop

The restored Old St. Patrick's in the West Loop