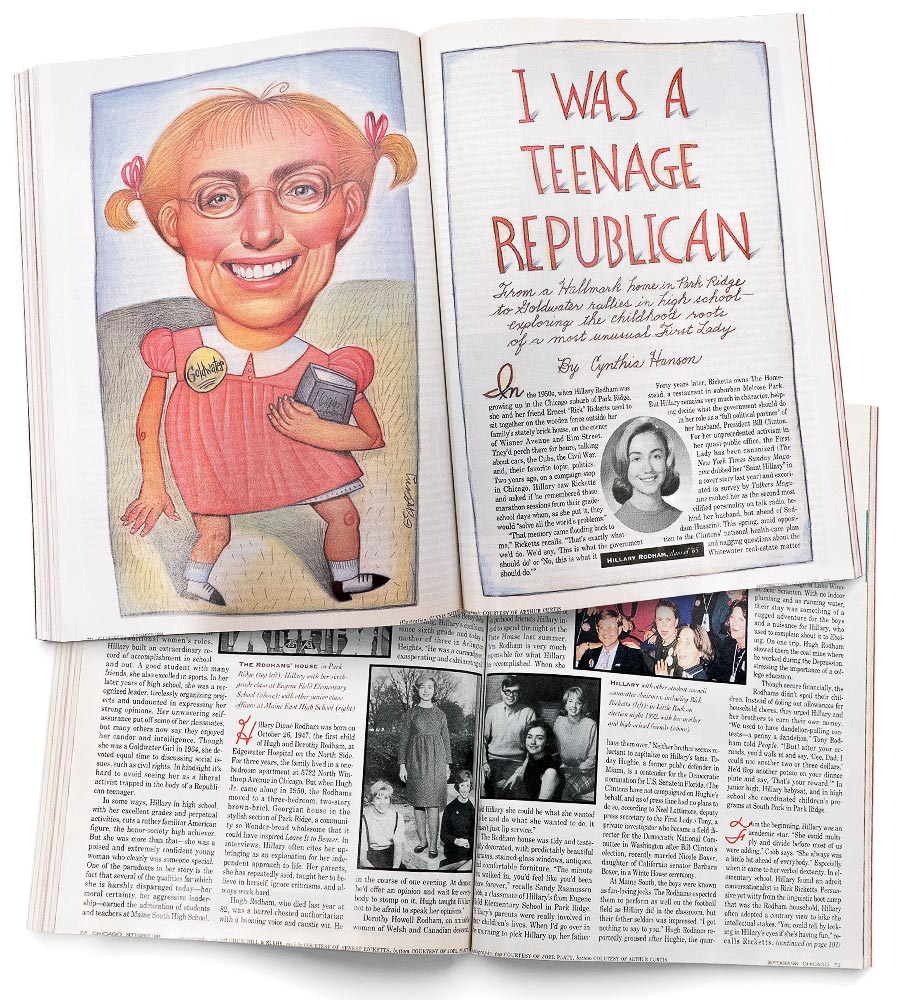

As the presidential election once more inches to the top of the news cycle, many Democrats are looking back to the last contender, Hillary Rodham Clinton, to see where the party faltered. In our September 1994 issue, published a year and a half into Clinton’s first term as first lady, writer Cynthia Hanson looked even further back, to Hillary’s childhood in suburban Park Ridge. In “I Was a Teenage Republican,” friends and former classmates attested to the ironfisted morality she exhibited at a young age, like when she found a litter of baby rabbits and enlisted pal Jim Yrigoyen’s help.

“She asked me to watch the rabbits while she went inside for a few minutes,” Yrigoyen recalls. “Well, one of the boys demanded a rabbit, and I succumbed to peer pressure, thinking Hillary didn’t know how many were there anyway. But when she returned, she counted the rabbits. ‘Were you a part of this?’ she asked. I confessed, and Hillary proceeded to punch me in the nose.”

She was similarly spirited in her support of Republican presidential hopeful Barry Goldwater in high school, parading through the halls in a “Goldwater Girl” sash, Hanson writes. To contextualize Clinton’s early political leanings, a childhood friend recounted the overwhelming cultural Republicanism of the well-to-do suburb at that time. If someone was a Democrat, he said, “we never talked about it.”

Read the full story below.

I Was a Teenage Republican

From a Hallmark home in Park Ridge to Goldwater rallies in high school — exploring the childhood roots of a most unusual First Lady

In the 1950s, when Hillary Rodham was growing up in the Chicago suburb of Park Ridge, she and her friend Ernest “Rick” Ricketts used to sit together on the wooden fence outside her family’s stately brick house, on the corner of Wisner Avenue and Elm Street. They’d perch there for hours, talking about cars, the Cubs, the Civil War, and, their favorite topic, politics. Two years ago, on a campaign stop in Chicago, Hillary saw Ricketts and asked if he remembered those marathon sessions from their grade school days when, as she put it, they would “solve all the world's problems.”

“That memory came flooding back to me,” Ricketts recalls. ”That’s exactly what we’d do. We’d say, ‘This is what the government should do’ or ‘No, this is what it should do.’ ”

Forty years later, Ricketts owns The Homestead, a restaurant in suburban Melrose Park. But Hillary remains very much in character, helping decide what the government should do in her role as a “full political partner” of her husband, President Bill Clinton. For her unprecedented activism in her quasi-public office, the First Lady has been canonized (The New York Times Sunday Magazine dubbed her “Saint Hillary” in a cover story last year) and excoriated (a survey by Talkers Magazine ranked her as the second most vilified personality on talk radio, behind her husband, but ahead of Saddam Hussein). This spring, amid opposition to the Clintons’ national health-care plan and nagging questions about the Whitewater real-estate matter and a lucrative commodities deal, exhaustive profiles in The New Yorker and Vanity Fair portrayed Hillary as manipulators and self-righteous, her true feelings and motives often maddeningly elusive. But nowhere in the recent flurry of coverage is much mention of her childhood in a comfortable, Republican Park Ridge home.

In fact, conversations with more than a score of her friends, classmates, teachers, and advisers from that time offer several clues to the making of this groundbreaking First Lady (she declined a request to be interviewed). The daughter of a rough-edged and demanding father and a mother who didn’t settle for traditional women‘s roles, Hillary built an extraordinary record of accomplishment in school and out. A good student with many friends, she also excelled in sports. In her later years of high school, she was a recognized leader, tirelessly organizing projects and undaunted in expressing her strong opinions, Her unwavering self-assurance put off some of her classmates, but many others now say they enjoyed her candor and intelligence. Though she was a Goldwater Girl in 1964, she devoted equal time to discussing social issues, such as civil rights. In hindsight, it’s hard to avoid seeing her as a liberal activist trapped in the body of a Republican teenager.

In some ways, Hillary in high school, with her excellent grades and perpetual activities, cuts a rather familiar American figure, the honor-society high achiever. But she was more than that—she was a poised and extremely confident young woman who clearly was someone special. One of the paradoxes in her story is the fact that several of the qualities for which she is harshly disparaged today—her moral certainty, her aggressive leadership—earned the admiration of students and teachers at Maine South High School.

Hillary Diane Rodham was born on October 26, 1947, the first child of Hugh and Dorothy Rodham, at Edgewater Hospital on the North Side. For three years, the family lived in a one-bedroom apartment at 5722 North Winthrop Avenue in Chicago. But when Hugh Jr. came along in 1950, the Rodhams moved to a three-bedroom, two-story brown-brick Georgian house in the stylish section of Park Ridge, a community so Wonder-bread wholesome that it could have inspired Leave It to Beaver. In interviews, Hillary often cites her upbringing as an explanation for her independent approach to life. Her parents, she has repeatedly said, taught her to believe in herself, ignore criticisms, and always work hard.

Hugh Rodham, who died last year at 82, was a barrel-chested authoritarian with a booming voice and caustic wit. He chewed tobacco, voted Republican, drove Cadillacs, and advocated “learning for earning’s sake.” Raised in Scranton, Pennsylvania, the son of English immigrants, Rodham won a football scholarship to Penn State University and majored in physical education. He took a job at the Scranton Lace Works Company, but wound up selling curtains in Chicago at the Columbia Lace Company, meeting his future wife when she applied for a secretarial job there. They exchanged letters during World War II—Rodham’s degree qualified him to train sailors in the navy’s physical fitness program—and were married upon his return in 1942. Rodham soon opened a textile business that made custom draperies for corporations, hotels, and airlines.

“Big Hugh’s presence really filled a room,” recalls Betsy Johnson Ebeling, Hillary’s confidante since sixth grade and today a mother of three in Arlington Heights. “He was a curmudgeon, exasperating and exhilarating all in the course of one evening. At dinner, he’d offer an opinion and wait for everybody to stomp on it. Hugh taught Hillary not to be afraid to speak her opinions.”

Dorothy Howell Rodham, an amiable woman of Welsh and Canadian descent, was born in Chicago, but grew up in Alhambra, California. In many ways, she epitomized the traditional cookie-baking, churchgoing, car-pooling, stay-at-home suburban mom of the 1950s. But Dorothy wanted more for herself—and Hillary. Once her children were in school, Dorothy, who had not gone to college, enrolled at Oakton Community College to “study whatever interested her,” Ebeling says. “She was the first mother I knew who went back to school.”

Indeed, Dorothy espoused feminist principles long before The Feminine Mystique inspired consciousness-raising in the early 1960s. “I never saw any difference in gender, as far as capabilities or aspirations were concerned,” she explained to The Washington Post a few years ago. “Just because [Hillary] was a girl didn’t mean she should be limited.” Says Judy Price Osgood, one of six girlhood friends Hillary invited to spend the night at the White House last summer, “Mrs. Rodham is very much responsible for what Hillary has accomplished. When she told Hillary she could be what she wanted to be and do what she wanted to do, it wasn’t just lip service.”

The Rodham house was tidy and tastefully decorated, with predictably beautiful curtains, stained-glass windows, antiques, and comfortable furniture. “The minute you walked in, you’d feel like you’d been there forever," recalls Sandy Rasmussen Cobb, a classmate of Hillary’s from Eugene Field Elementary School in Park Ridge. Hillary’s parents were really involved in their children’s lives. When I’d go over in the morning to pick Hillary up, her father would be helping them with their math homework in the kitchen. He’d quiz the boys on math problems, and Hillary would chime in, too.”

The “boys,” as they’re still called, are Hughie and Tony (born four years after Hughie). “They’re full of life, the type of people who always make you laugh,” says Ebeling. “If you’re going to have a party on Saturday night, you’d definitely want to have them over.” Neither brother seems reluctant to capitalize on Hillary’s fame. Today Hughie, a former public defender in Miami, is a contender for the Democratic nomination for U.S. Senate in Florida. (The Clintons have not campaigned on Hughie’s behalf, and as of press time had no plans to do so, according to Neel Lattimore, deputy press secretary to the First Lady.) Tony, a private investigator who became a field director for the Democratic National Committee in Washington after Bill Clinton’s election, recently married Nicole Boxer, daughter of California senator Barbara Boxer, in a White House ceremony.

At Maine South, the boys were known as fun-loving jocks. The Rodhams expected them to perform as well on the football field as Hillary did in the classroom, but their father seldom was impressed. “I got nothing to say to you,” Hugh Rodham reportedly groused after Hughie, the quarterback, completed 10 of 11 passes in his best game, “except you should have completed the other one.” Hillary faced the same tough standards. She'd bring home straight A’s, and Hugh would mutter, “You must go to a pretty easy school.”

By all accounts, the Rodhams were a tight-knit, Hallmark-moment kind of family. They worshiped at the First United Methodist Church. They played pinochle, a card game of logic and shrewdness. And, as Hillary confessed during her command-performance news conference in April 1994, she learned to read stock tables on her father’s knee. Every summer, Hugh Rodham packed up the Cadillac and hauled the family to a cabin at the edge of Lake Winola, near Scranton. With no indoor plumbing and no running water, their stay was something of a rugged adventure for the boys and a nuisance for Hillary, who used to complain about it to Ebeling. On one trip, Hugh Rodham showed them the coal mine where he worked during the Depression, stressing the importance of a college education.

Though secure financially, the Rodhams didn’t spoil their children. Instead of doling out allowances for household chores, they urged Hillary and her brothers to earn their own money. “We used to have dandelion-pulling contests—a penny a dandelion,” Tony Rodham told People. “[But] after your errands, you’d walk in and say, ‘Gee, Dad, I could use another two or three dollars.’ He‘d flop another potato on your dinner plate and say, ‘That’s your reward.’ ” In junior high, Hillary babysat, and in high school she coordinated children’s programs at South Park in Park Ridge.

From the beginning, Hillary was an academic star. “She could multiply and divide before most of us were adding,” Cobb says. “She always was a little bit ahead of everybody.” Especially when it came to her verbal dexterity. In elementary school, Hillary found an adroit conversationalist in Rick Ricketts. Persuasive yet witty from the linguistic boot camp that was the Rodham household, Hillary often adopted a contrary view to hike the intellectual stakes. “You could tell by looking in Hillary’s eyes if she‘s having fun,” recalls Ricketts.

“There’s a spark, and you know that it’s an academic debate—it’s not personal.” Hillary liked school—and teachers adored her. But she was more than a bookworm. The Rodhams made sure she could dance, swim, and thrive on the baseball diamond. In one widely reported family legend, Hillary endured daily batting and fielding practice at Hinkley Park, until she could smash a fastball and catch a pop fly. “When the other girls were jumping rope at recess, Hillary was playing softball with the boys,” says Jim Yrigoyen, now a guidance counselor at Lake Zurich High School.

Young Hillary—round of face, muscular of body—had short, dark blond hair, thick brown eyebrows, and a friendly smile with a developing overbite. She wore typical girl fashions— crisp blouses, pleated skirts, sailor dresses, bobby socks, saddle shoes. Her thick glasses obscured her big blue eyes. Even so, she was noticing boys, and they were noticing her. Yrigoyen gave Hillary his “dog tag”—the identification many Park Ridge children wore at the time—in the supreme act of preteen puppy love. But the romance ended abruptly. "We were running around in the snow drifts, and I washed Hillary‘s face in the wet snow,” he says. “I must have done it too hard and hurt her, because when I got to school the next day, I found my dog tag on my desk.” A year later, he would see an even tougher side of his first flame. Hillary had forgiven Yrigoyen enough to resume a polite friendship, and she enlisted his help in protecting some baby rabbits in her backyard from neighborhood boys who were trying to steal them. “She asked me to watch the rabbits while she went inside for a few minutes,” Yrigoyen recalls. “Well, one of the boys demanded a rabbit, and I succumbed to peer pressure, thinking Hillary didn't know how many were there anyway. But when she returned, she counted the rabbits. ‘Were you a part of this?’ she asked. I confessed, and Hillary proceeded to punch me in the nose.”

Betsy Johnson Ebeling met Hillary in Mrs. King’s sixth grade class. With mutual interests in Nancy Drew, Johnny Mathis, and Saturday matinees at the Pickwick Theater, they became fast friends—two good girls who excelled at everything they tried… almost. Their mothers signed them up for piano lessons with the eccentric Margaret-Lucy Lessard, who, in a move straight from The Music Man, went door-to-door, promising parents that she’d turn their kids into mini Mozarts. The lessons were given in Lessard’s living room, dark except for a tiny light near the piano. Nearby, her dead stuffed Pomeranians stared at them from a glass case. “Her [live] Pomeranian growled the whole time we were there,” Ebeling says. "We just wanted to get out of her house.” The two girls teamed up for a duet at the spring recital. “Hillary had the bass, and I had the top part for Marche Militaire,” Ebeling says. “But she didn’t change the notes—just the tempo. It would get really slow, then really fast. Our piano future was down the drain.”

By adolescence, the adult Hillary was starting to emerge. Then, as now, her intellect and focus both impressed and intimidated her peers. “In sixth grade, the biggest putdown girls had for each other was, ‘Oh, she’s so conceited,’ ” says Ebeling. “It took a while for people to understand that Hillary wasn’t conceited. She was just very self-confident. She was very comfortable with herself. She wasn’t afraid to go against the crowd over something she believed in.”

In the post-Sputnik era, President Kennedy aggressively promoted the national race into space, and Hillary decided she wanted to be an astronaut. She wrote to NASA for the educational requirements. “Girls need not apply,” the return letter said. Hillary has called NASA’s response “infuriating,” but as she told The Washington Post, “I later realized that I couldn’t have been an astronaut anyway, because I have such terrible eyesight.”

Hillary became a tireless volunteer, organizing a baby-sitting brigade for the children of migrant workers in Des Plaines and hosting variety shows at local senior centers. Even her fun had an element of self-discipline. A competent tennis player in search of a partner, Hillary drafted a “contract” that spelled out the terms for her to teach Ebeling the game. “The agreement was something like, Hillary would give me so many tennis lessons, and I would try [to practice],” Ebeling says. “It probably was her first legal experience.”

Hillary’s friends say that she was interested in boys, but not “boy crazy,” as Ebeling puts it. “She had a crush on Don Wasley, the cutest boy in the eighth grade,” Ebeling says. “He had blond hair, blue eyes. But he moved away before high school, and no one knows what happened to him. During the [Presidential] campaign, I joked that I was going to wear a T-shirt that said, WHERE’S DON WASLEY?”

Jim Yrigoyen was out as her boyfriend, but he recalls that she stepped in when he was having problems in junior high. “One day, as we got off the bus and started walking home, Hillary said, ‘I think you’re a nice person, and I’m concerned about your missing school and getting detentions,’ ” Yrigoyen says. “She didn’t pry; she just said what was on her mind in a very caring, sensitive way. It was the right comment at the right time. It really helped me turn things around.”

Until she was 13, Hillary’s intellectual life centered on home, school, and church, places that nurtured conservative ideas about the world. But in 1961, she met Don Jones, a newly ordained and happily existentialist youth minister at First United Methodist. She sat in the front pew, as Jones recalls, and “seemed to be on a quest for transcendence.” By the time Jones left in 1963, to begin doctoral studies back east, Hillary had blossomed into an ardent social activist. “He just was relentless in telling us that to be a Christian did not just mean you were concerned about your own personal salvation,” she once told Newsweek.

Jones called his youth group “The University of Life,” and he exposed it to a series of education and social-action programs in which he used pop culture to teach theology and social responsibility. He introduced Hillary and her friends to the poetry of e. e. cummings, the music of Bob Dylan, the Christian symbolism of van Gogh’s Starry Night, the bittersweet films of François Truffaut. “Don presented the material in a very thoughtful way and on a level that was very comfortable to us,” Ricketts says. “It wasn’t like, ‘Hey, you kids have been sheltered.’ It was like, ‘Hey, have you ever read Catcher in the Rye? What do you think motivated Holden Caulfield to behave the way he did? Why was he so angry?’ We’d talk about how it related to Methodism. Don could tie all those things together.”

Once, Jones debated an atheist on the existence of God; another time, he led a discussion about teen pregnancy. This was heavy stuff for the young Methodists of First United, who'd heard only the gospel of “be nice” from the church’s traditional ministers. “In suburban Park Ridge, you never would have known that a great social revolution was going on,” says Jones, now professor of social ethics and chairman of the religion department at Drew University in New Jersey. “Preachers didn’t deal with social injustices like segregation and racial discrimination.”

Jones organized trips to a youth center on the South Side of Chicago, where the students met black and Latino teens. In April 1962, he took the group to hear Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. speak at Orchestra Hall. King’s provocative address— “Remaining Awake Through a Revolution”—seemed scripted for the sheltered youngsters. “While I can’t say what [the experience] meant to Hillary back then, when I visited her in Little Rock in 1984, she reminded me that I took them backstage to meet Dr. King, and she said it meant a lot to her,” Jones recalls.

Hillary would often drop by Jones’s office after school to discuss the Bible or politics. “She loved to have her mind stretched, and she loved to read difficult material,” says Jones, who introduced her to the writings of Paul Tillich and Reinhold Niebuhr. “When Hillary was 14, I gave her a copy of [J.D.] Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye. She probably didn’t completely understand it or couldn’t, because she came from a wholesome family. She wrote me a letter from Wellesley that said, ‘I reread Catcher in the Rye. I didn’t like it when I first read it, but now I do.’ I still have that letter. The mere fact I saved every letter Hillary ever wrote to me indicates there was something special about her.”

Hillary entered Maine East High School in 1961. By 1964, the student body had outgrown the facility and Maine East split; all students, including Hillary, who lived south of Oakton Street transferred to the new Maine South, a sprawling campus with a picturesque pond out front, located just a few miles away. To see Hillary in action as First Lady is to observe the mature Hillary Diane Rodham as she campaigned in the halls of Maine East and Maine South for herself, for Barry Goldwater, for whatever cause she deemed just. “Hillary today is just like she was 30 years ago,” says Timothy Sheldon, who beat her in the race for student council president when they were juniors and who today is an associate judge in Kane County. Paul Carlson, a history teacher at Maine East, recalls that she wrote a 75-page term paper for his world civilization course when she was a freshman.

“Hillary cut a very singular figure for herself,” he says. “She led in class discussions, and she wasn’t afraid to give her point of view in a very strong voice.” He adds, “She spoke in a very clipped way. Her sentences were cut off at the period. Bing, bing, bing.” (Carlson, an avowed conservative, says he was “crushed” seven or eight years later when he saw her on Irv Kupcinet’s TV show dressed as a hippie and spouting leftist ideology.)

She led an active social life—parties, sock hops, and basketball games with a coed crowd, high achievers all. They didn’t drink. Or smoke. Or stay out late. Or have sex. Or if they did, they didn’t dish details. Sex was a major topic, though purely in the abstract. Hillary had dates for homecoming dances and proms, but never a steady boyfriend. Her girlfriends claim she was too busy for full-time romance. Her male friends gave a more mixed assessment. One classmate, who admits that his pulse still races when he sees Hillary on TV, thinks she was too picky. "A lot of us had crushes on Hillary, but she seemed unattainable,” he says wistfully. “She wouldn’t pay any attention to me or anyone else. One year, a wrestler from Morton Grove announced he was going to make Hillary Rodham his sexual conquest. We laughed, because we knew it would never happen.”

But other male classmates say Hillary’s plain looks discouraged romance. She had an average figure and thick legs; she wore unflattering purple glasses and unfashionable sack dresses. “Hillary wasn’t considered a great catch,” a friend admits. (Like others quoted anonymously, he doesn’t want his name attached to any critical comments about Hillary.) “Guys didn’t think she was attractive,” he continues. “They liked girls who were ‘girlish.’ Hillary was ‘womanish.’ She is far more attractive today than she was in high school.”

But Hillary apparently cared enough about her image to pay attention when it mattered. In yearbook photographs, it almost seems as if Hillary knew she was posing for posterity: Hair styled in a Marlo Thomas flip, she bears little resemblance to the deliberately dowdy teenager classmates describe. In tailored ensembles, she looks more sophisticated than the tight-sweatered girls around her. (Hillary’s grooming would remain an afterthought for her for years. At Wellesley, she became a disheveled hippie, and in Arkansas, she turned frumpy, hiding her highlight-craving brown hair beneath headbands, wearing matronly clothes, and eschewing contact lenses for enormous glasses.)

“While we were preoccupied with boys, hair, nails, makeup, and the telephone, Hillary was trying to fix problems or make things better,” says Jeanie Snodgrass Almo, who owns and operates childcare centers in Washington, D.C. “She had such a great self-worth that she didn’t get preoccupied with those other more frivolous, traditionally adolescent issues. She seemed to have an inner peace.”

Hillary loved being on stage, though her performing talent was limited to acting. She was so tone-deaf that Hal Chastain, the late drama teacher, politely urged her to mouth the words to the opening song from Bye Bye Birdie, which she and her friends performed in Maine East’s 1963 Variety Show. “He joked that we were unquestionably the worst act, but since we were such a large group, he was afraid if he kicked us out, it would diminish ticket sales,” Ricketts says. But in 1965, Hillary drew rave reviews as Carrie Nation in a skit about temperance. As four girls behind her pretended to chug liquor, Hillary stood center stage, clutching her throat and railing against the evils of alcohol. “She was a real ham,” recalls Ellen Press Murdoch, the show’s codirector. “We thought it was terribly funny.”

But of all the images of Hillary that classmates remember—canoeing on Murphy Lake as a Mariner Scout, demonstrating exercises as a gym leader, lobbying for a joint senior prom after the opening of Maine South—the most vivid is Hillary as Organizer. She was vice-president of the junior class, and, as a student council representative, she maneuvered her way onto the most prominent committees. Cultural Values allowed her to review the dress code (friends recall she supported it), and Organizations allowed her to rewrite the council’s constitution. For Hillary and her friends, these projects were serious business, even if the particular concern was only choosing a theme for homecoming or selecting the music for prom.

“When you had to say ‘no’ to Hillary because school officials felt [the project] wasn’t a good move, you’d better be able to support that decision because she’d question it,” recalls Kenneth W. Reese, former student council adviser and now director of guidance at Maine South.

Ricketts watched her in action with the late Dr. Clyde Watson, Maine South’s principal. “Hillary wanted the student council election [in the spring of 1965] to be a carbon copy of the national conventions—nominating speeches, demonstrations, signs,” he says. “She had all of this material written down, and a group of us went to see Dr. Watson. The administration was very conservative, and they were taking away the extracurricular things we’d had at Maine East, like all-school assemblies. But Dr. Watson was completely blown away by Hillary’s plan, and he approved everything. She recruited everybody to work on it, and it turned out exactly as she’d envisioned it.”

Not everyone in Maine South was a fan, however. “Hillary was so take-charge, so determined, so involved in every single activity that you’d think, ‘Why don’t you chill out a bit? Why don’t you give somebody else a chance?’ ” recalls a female classmate. “I always felt Hillary thought she knew what was best, so that’s what everybody should do. It’s the same attitude with health care—Hillary knows what’s best for the country, and we should just go along.” Adds a male classmate, “She could be abrasive. She definitely could get on her high horse.”

One of her classmates was Penny Pullen, who went on to become a Republican state legislator with deeply conservative views. They were acquaintances, not friends, and Pullen says today, “She was always ambitious, but she’s certainly not Saint Hillary in adulthood.”

Even her friends remarked on her unwavering moral certainty. In an English class, “the question came up about a moral system, and whether you could live by an absolute code of right and wrong,” says Arthur W. Curtis, class valedictorian and now a doctor in Chicago. “Hillary said you could. It’s a very WASP characteristic, her strong sense of right and wrong.”

In January 1993, Rick Ricketts, along with ten of Hillary’s other childhood friends, went to the White House to celebrate Bill Clinton’s inauguration. At a dessert party in the Blue Room, he saw Dorothy Rodham, Hillary’s mother. “I said, ‘How in the world did Hillary get to be a Democrat?’ And Dorothy replied, ‘I was a Democrat,’ ” Ricketts recalls. “I said, ‘Oh, so was my mother, but we never talked about it.’ In Park Ridge in the 1960s, it wasn’t really accepted to be a Democrat. Everybody was a Republican.”

Through the election of 1964, Hillary held with the politics of Park Ridge and of her father, a devout Republican, who is said to have crossed party lines only to vote for Bill Clinton. She stayed Republican, even though the Presidential election that year brought the U.S. political scene into unusually sharp relief, with Republican Barry Goldwater trumpeting small government and Democrat Lyndon Johnson organizing his Great Society program of social reforms.

Betsy Johnson Ebeling says Goldwater‘s political manifesto, The Conscience of a Conservative, reinforced the Republican gospel preached in their homes. “[Hillary and I] both read the book and found it very striking—Goldwater’s championing of the individual,” she says. Wearing sashes that screamed GOLDWATER GIRL, Hillary and Betsy recruited classmates for Republican rallies, and, under the wing of local Republican leaders, went down to 26th and Wentworth to check voters’ registrations.

Ellen Press Murdoch, one of the few Johnson supporters at Maine South, says she took “an incredible amount of heat [from Hillary] for being a bleeding-heart liberal. By my early 20s, I became a Republican. Our senior year in high school was as liberal as I ever got and as conservative as Hillary ever got.”

After Goldwater’s defeat, Hillary and Betsy focused on college applications and spring vacations. In December 1964, they were deluged with invitations to teas held by local alumnae of prestigious East Coast schools. Sometimes, Hugh Rodham would drive the girls, dressed in their Sunday best. As Ebeling recalls, he usually traveled with a wad of tobacco in his cheek. “When we’d come to a stoplight,” she says, “Hugh would open the door and spit.” When they’d get to the hostess’s house—typically on the North Shore—Hugh would sit outside in his gold Cadillac, reading the Tribune, while the girls were inside, drinking tea.

In June, Hillary finished in the top five percent of her class, became a National Merit Scholar finalist, and won the social studies award at graduation. No one blinked when the faculty gave her the Daughters of the American Revolution Citizenship Award. Or when Maine South’s Class of 1965 voted Hillary the girl most likely to succeed.

That September, she headed to Wellesley College, outside Boston (and 1,000 miles away from Hugh Rodham’s influence)—embarking on a life of extraordinary success and controversy. By the time she graduated from college in 1969, Hillary had organized campus teach-ins on the Vietnam War, campaigned for antiwar Democrat Eugene McCarthy in the 1968 primaries, and worked for Senator Hubert Humphrey, the Democratic nominee, in the general election.

She never again lived full-time in Park Ridge, and in 1987, her mother and father sold the house on Wisner Avenue and moved to Little Rock, Arkansas, to be near Hillary and Governor Bill Clinton and their daughter, Chelsea. (Earlier this summer, following extensive renovations, the new owners resold the house for an amount reportedly near the asking price of $459,900.)

Over the years, Hillary has remained close to her childhood friends. These days, when she’s in Chicago—whether to address the American Medical Association, throw out the opening-day first pitch at Wrigley Field, or celebrate the start of the World Cup, she almost always manages to squeeze in some off-the-record fun with the old gang, a group whose number can climb to 50, depending on the event. (The 30th reunion for Maine South’s Class of ’65 may be held in Washington, D.C., next year, with a visit to the White House included among the scheduled events.) “She remembers her friendships, and she services them lovingly,” says Ebeling. “We’ve always kept in touch—family and friends are part of all of the events in [her] life.”

In July 1992, at the Democratic National Convention in New York City, Ebeling was standing next to Hillary in a box at Madison Square Garden as Bill Clinton strolled onto the stage to accept the presidential nomination. Suddenly, Hillary grabbed Ebeling’s hand. It was a surreal moment for these daughters of Park Ridge, who’d come so far since they bombed at the piano recital. Critics of the First Lady would have you believe that at that very moment, she was plotting to become co-President and leave her mark on American history. Ebeling knows otherwise. “I don’t know why this came into my head,” Ebeling says, “but all I could say was, ‘To think, all you wanted in the eighth grade was Don Wasley.’ ” As the applause thundered and the celebration began, Hillary Rodham Clinton was trying to stifle a laugh.

Comments are closed.