This story was originally published in the September 2020 issue, before Candyman’s theatrical release was rescheduled to 2021 due to the pandemic; the movie will open in theaters August 27.

In the Illinois exurb where I spent my childhood, my dad’s cousin owned a movie rental shop called Video Vision. If I made the two-mile round trip by bicycle, I had carte blanche to rent any title other than those shelved beyond the saloon-style doors that led to the adults-only section. By the time I’d entered fifth grade, in the early ’90s, I had fallen in love with Chicago by way of VHS tapes. The Blues Brothers, Risky Business, Ferris Bueller’s Day Off — those movies made the big city 100 miles east of my tiny hometown seem like a place of untold thrills and comic misadventures.

Candyman was altogether different, something heavier and more mysterious. British director Bernard Rose’s 1992 cult classic, which spawned two sequels and a durable urban legend, got its hooks — or rather, hook — into me early and has never let go. The film, about the ghost of a long-ago lynching victim terrorizing the Cabrini-Green housing project with a very sharp prosthetic, was at once a nightmarish portrait of urban life, an alluring puzzle of mistaken identity, and the rare slasher flick to examine race and inequality in America. The year of the movie’s release, Chicago’s violence reached a grisly apex: 943 homicides and the highest per capita murder rate in the city’s history. The Chicago Housing Authority’s dilapidated projects had become the ultimate symbol of the dysfunction of the American “inner city,” a source of unchecked fear and paranoia around the issues of crime and poverty. And Cabrini-Green was the poster child, its towers looming in Rose’s film like so many haunted houses just beyond the Gold Coast.

When I first heard that Jordan Peele, the horror auteur behind Get Out and Us, was resurrecting Candyman in the form of a “spiritual sequel,” my fascination was reawakened, and I was suddenly compelled to look deeper into the original movie’s curious origins.

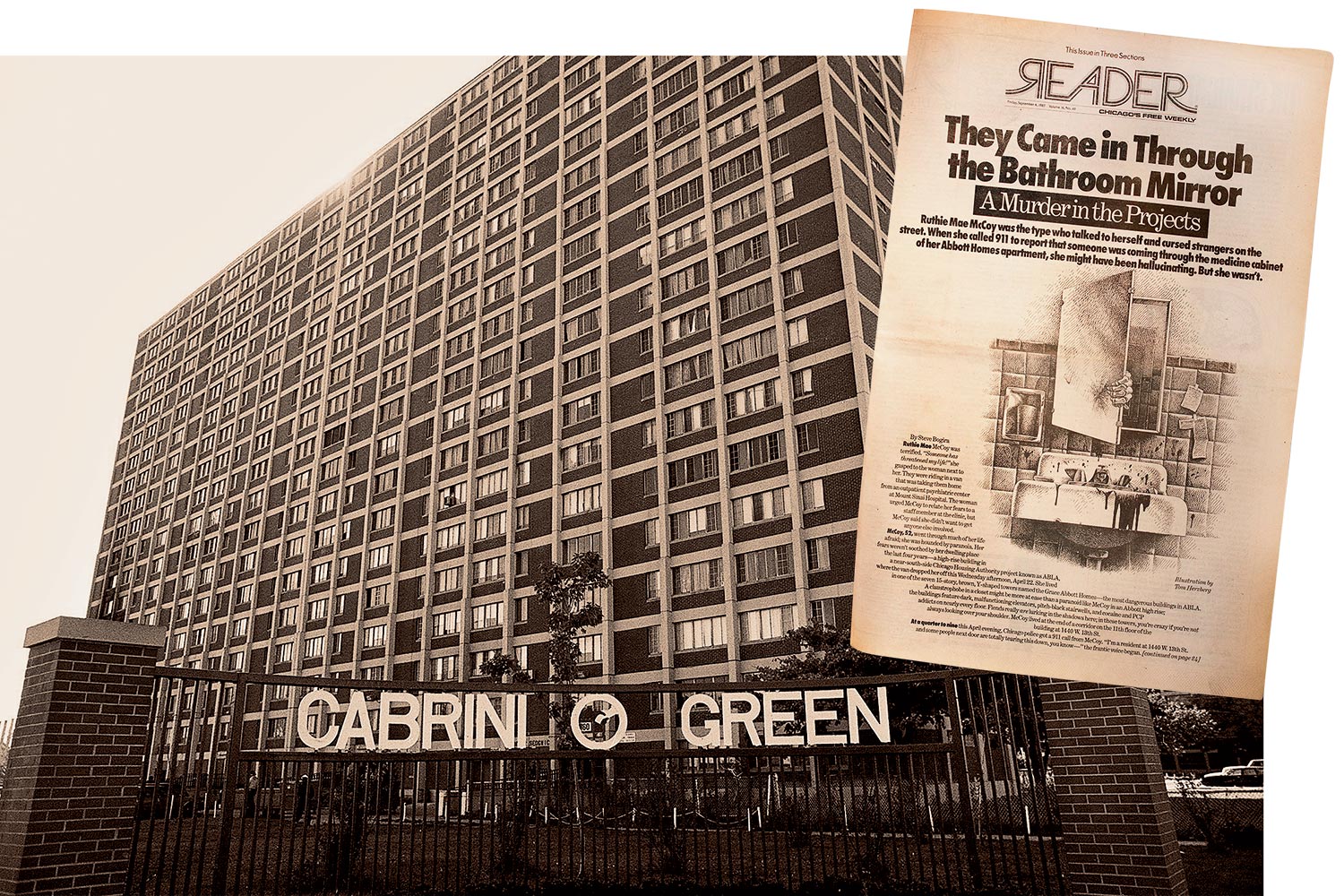

To get at the real horror behind Candyman, I knew I had to talk to Steve Bogira. Now 66, the veteran journalist covered race and poverty for the Chicago Reader from 1981 through 2016 (including during part of my tenure as the alternative weekly’s editor in chief). While Candyman’s credits say that Rose based his script on the Clive Barker short story “The Forbidden,” it was Bogira’s reporting on a chilling murder in one of the city’s housing projects that inspired what is perhaps the movie’s best-remembered detail: Candyman’s frequent mode of entry, a bathroom mirror.

The bizarre crime Bogira detailed occurred in April 1987, when a 52-year-old resident of the Grace Abbott Homes named Ruthie Mae McCoy was fatally shot by an intruder who entered her 11th-floor apartment through an opening behind the bathroom’s medicine cabinet. A police blotter item on the incident intrigued Bogira, and he began reporting on the case. He spoke to a janitor at McCoy’s building, who let him into the woman’s residence and introduced him to neighbors. What Bogira discovered was that for at least a year criminals in the Near West Side high-rise had been exploiting a flaw in the building’s architecture, breaking from one apartment into another through a narrow cavity between the medicine cabinets. “I was struck by the idea that not only was this a nightmarish, unreal crime that had happened to Ruthie Mae,” he says, “but these residents were living with this particular fear and nobody was doing anything about it.”

Compounding the dread was the fact that McCoy’s cry for help went basically unanswered. She dialed 911 and reported the break-in in progress. Two neighbors also independently called to report gunshots. It took officers almost a half hour to arrive. No one answered their knocks at McCoy’s locked door. A janitor tried a key that didn’t work. Eventually the officers left without entering. Nearly two days later, a CHA official found McCoy’s corpse decomposing on her bedroom floor.

Not long after Bogira’s 10,000-word feature, “They Came in Through the Bathroom Mirror,” was published in the Reader in September 1987, he got a call from John Malkovich. The actor had read the story while in town starring in Steppenwolf Theatre’s production of Lanford Wilson’s then-new play Burn This at the Royal-George Theatre. Malkovich thought the article had the makings of a movie. At a bar near the theater, Malkovich sat down with Bogira to make his pitch.

“He was genuinely interested in telling the story of the residents of the projects and how difficult their lives could be,” Bogira recalls. There was just one problem: In order to attract production financing, Malkovich told him, the film’s lead character would need to be a white reporter who would lead viewers into the world of the Chicago projects. “I let him know right away that I felt uncomfortable with that idea,” says Bogira, who is white. “You’re right,” Bogira recalls Malkovich replying. “Ideally the lead characters should be actors portraying Black project residents. But you’re not going to find someone to fund that kind of movie.” As the meeting wrapped up, Malkovich said he would gauge interest among Hollywood producers. The reporter never again heard from the actor. (My attempts to reach Malkovich to confirm Bogira’s account were not successful.)

In 1993, some months after Candyman’s release, an editor at the Reader mentioned to Bogira that he had observed some striking similarities between the film and Bogira’s reporting on the Ruthie Mae McCoy murder. In the movie, University of Illinois at Chicago grad student Helen Lyle (Virginia Madsen) hears from a university janitor that a Cabrini-Green resident named Ruthie Jean has been brutally killed by an assailant who came in through her medicine cabinet. Helen interviews a neighbor of the victim, Anne-Marie McCoy.

“It was surprising to me that they changed so little,” Bogira says of the movie. Yet he suffered no great disappointment seeing his contribution go uncredited. “It seemed like what Malkovich and I talked about had played out: A film got made and a white person was in the lead.”

Ever since then, Bogira has assumed that his meeting with Malkovich somehow injected the story of the Chicago medicine cabinet murder into Hollywood’s bloodstream. But Candyman creator Bernard Rose told me a different story.

In 1990, Rose sold the Candyman concept to Propaganda Films, the risk-taking production company that had funded David Lynch’s Twin Peaks and Wild at Heart. He wrote an initial draft of the screenplay, moving the action of Barker’s tale from a Liverpool council flat to the Chicago projects. “I had been to Chicago a few times, but it wasn’t like I knew the city particularly well,” he says. “I asked that before writing the next draft, I’d like to go there and do some proper research and really get to know the city.”

When he arrived in July 1990, Rose and reps from the Illinois Film Office, accompanied by a police escort, toured Cabrini-Green and the Robert Taylor Homes. “The level of fear and anxiety around these places from the film commission people and the cops I found quite shocking, really,” Rose recalls. Later in the trip, he returned unaccompanied to eat dinner with a CHA resident. “Once the door was closed, it was just an apartment,” he says, “and a quite well-located apartment.” The two encounters informed the film’s ideas about the gulf that can form between perception and reality, and how that disconnect can curdle into bigotry.

While in town, Rose picked up a copy of the July 12 edition of the Reader in which Bogira’s follow-up to his 1987 investigative piece happened to appear. Titled “Cause of Death,” the feature posed the question “What killed Ruthie Mae McCoy — a bullet in the chest, or life in the projects?”

“Wow, here’s some serendipity!” Rose said to himself after reading about McCoy’s murder. “I’ve got to put that in the movie.” Aptly enough, in Candyman, Helen pores over newspaper microfilm, coming upon a story in the fictional Chicago Dispatch headlined “Cause of Death, What Killed Ruthie Jean? Life in the Projects.”

Later, when Candyman was in preproduction, Bogira received a vague letter asking him to serve as a consultant on a movie that would be shooting in the Chicago projects. “They offered me pocket change and a screen credit,” he says. “I responded, ‘Send me the script. If it’s not exploitative, I’ll consider helping you out.’ ” He never heard back. (Rose says he had no knowledge of the correspondence.)

No horror buff himself, Bogira hasn’t much pondered Candyman over the years. “I didn’t think about urban legends, because the urban reality of Chicago was so horrible,” he says. “You didn’t need to make things up to tell a story about something that had a lot of horror in it. This was real life for people that were living in high-rise public housing.” When I talked to Ben Austen, the author of High-Risers, a 2018 history of Cabrini-Green, he pointed out that it was exactly such “muddling of real and imaginary” that elevated Candyman above the typical horror fare — the conflation of the actual dangers of the Chicago projects and the trumped-up terror in the public imagination.

On October 13, 1992, three days before Candyman premiered in theaters, a gunman perched in a Cabrini high-rise shot and killed Dantrell Davis as the 7-year-old and his mother walked the 30 yards from their project building to the elementary school he attended. The killing made headlines nationally, sparking widespread outrage and paving the way for the CHA’s Plan for Transformation, which laid out provisions for the systematic demolition of Chicago’s high-rise public housing. The last Cabrini-Green tower was razed in 2011. The neighborhood is now filled with market-rate condos and has an indoor skydiving center.

This is where the new Candyman sequel, written by Peele and director Nia DaCosta, picks up. The film’s protagonist is a Black millennial artist named Anthony McCoy (Yahya Abdul-Mateen II), who resides in one of those lofty condos. Through a chance meeting with a resident of the sparsely occupied Cabrini row houses — the last vestige of the project buildings — Anthony hears of Candyman and introduces the lore into his art practice, inadvertently breathing new life into the supernatural slayer, whose existence, like all urban legends, hinges on a kind of collective belief.

And so, while the Cabrini-Green towers may be gone, the legend they seeded has proved harder to kill.