In 2016, Christina Whitehouse, then a Northwestern University master’s student, was cycling in the Loop when a commercial truck turned right, veering into the bike lane and nearly running her over. The next year, after realizing how pervasive the problem of drivers not respecting dedicated lanes was, she launched the app Bike Lane Uprising. It allows cyclists to log the location and submit photos of vehicles parked in bike lanes, which is illegal in Chicago. The nationwide data is sortable, enabling users to spot trends. Whitehouse provides the information to city officals and companies employing drivers so they can identify problem areas and repeat offenders.

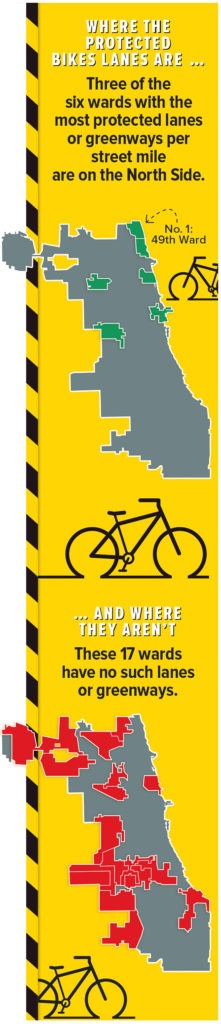

Still, it’s been an uphill climb to improve bike safety in Chicago. In the first seven months of this year, there were five cyclist fatalities here. That’s on top of 10 in 2021, according to local transit website Streetsblog. In June, 3-year-old Lily Grace Shambrook was killed by a semi while riding on the back of her mother’s bike in Uptown. A truck parked in a bike lane forced her mother to maneuver into traffic, where the semi struck the bike. That and other recent incidents led to renewed calls from cyclists for safer streets and more towing of vehicles blocking lanes. The Chicago Department of Transportation will install concrete barriers on all protected bike lanes by the end of 2023.

Bike Lane Uprising data is crowdsourced. Why go that route?

I come from the design world. And I come from the notion that the more you know about a problem, the more opportunities you have to solve it. How can we filter and sort and visualize the problem in a way that gives you a quick idea of what’s happening? By creating this aggregate, we can show more of a complete picture. We’re trying to identify tangible opportunities to make things safe.

How exactly is the data being used to make changes?

Out on the streets, it’s becoming a bit of a nudge psychology, that cyclists aren’t standing for it anymore. When I started this, a lot of cyclists said, “I didn’t even realize that it wasn’t OK to park in the bike lane.” It has been used for infrastructure, to identify locations that have problems. [The Chicago Department of Transportation] has the guerrilla traffic study we did on DuSable Lake Shore Drive after Gerardo Marciales was killed there [in February]. Within a week, there were bollards put up. Do I think that we were the only reason? Probably not, but it’s another voice saying yes to infrastructure. You can look at the photos [on the app] and see what the actual location looks like and how people are parking. We saw, with Lily’s death, that there was a driver of a ComEd vehicle parked illegally in a bike lane. [ComEd’s drivers] are repeat bike lane offenders. But there are other companies that, when they find out about it, they’re like, “We’re going to address this.” Some even attach performance metrics to it.

Unfortunately, it often takes a death to create change. How would you assess our progress in terms of improving the infrastructure for safe biking in Chicago?

It’s so incredibly slow, it’s stagnant. [Consider] the fact that our mayor is trying to bring in NASCAR and free gas cards, and nobody’s using public transit. Whenever you see a quote-unquote trendy neighborhood in any city, they always show cyclists. But for some reason, our mayor has taken a stance to just double down on showcasing car culture. It’s been reckless, and it’s been dangerous.

Are our problems here unique?

Parking in bike lanes seems to be pretty commonplace. The egregiousness, that’s where it starts to kind of separate, and the driving habits, the tone. I’ve traveled around the country quite a bit, and I am taken off guard when I go to some other places, because it’s just chill. The drivers seem happier, and they aren’t trying to hit me on purpose. The situation here recently, the drivers are so incredibly aggressive, so incredibly reckless. There’s a lot of people who say, “I’ve biked in Chicago for 10, 15, 20 years, and this is the worst it’s ever been.”

How do we fix this?

Political will. You have city officials that fear that they won’t get elected or reelected if they take away somebody’s street parking. Unfortunately, we set driving on this pedestal as if it’s a God-given right. There are areas of Chicago that do not have the same level of access to public transit as more affluent neighborhoods. Instead of giving away gas cards and parking spaces, we should be focusing on building our public transportation and bike lanes. Safe bike lanes are a way to provide access to opportunity at a low cost.

There seems to be more people demonstrating for safer streets for cyclists. You have even literally sat on the ground to block motorists parked in bike lanes.

You’re seeing this growing momentum — kind of an uprising, right? The cycling community is growing in numbers. We saw during the pandemic, biking exploded. With that, there are more people who have an invested interest in this. There are a lot of people who are no longer going to sit by and allow their lives to be put at risk. There are so many different niches within the biking world: fixie kids, cargo bike moms, the Rapha crew, commuters with the milk crates. Biking in general is very segregated. Chicago is very segregated. But what you’re seeing is, we’re kind of overlapping now. We’re creating this group dynamic. It’s growing our political will and moving the needle.

What’s the hope you have right now for the city to become better for cyclists?

We just want safe spaces to bike. Most of the time, cyclists are doing jujitsu figuring out how they’re going to get somewhere based on how safe it is. There’s always going to be people who try to drive on the lakefront path, and something needs to be done in that regard. But for 90 percent of the other problems, good, safe, solid infrastructure can fix it. And the safer we make biking, the more people are going to bike, and we’re going to have a culture shift.