If the unspoken ambition of every human being is to make the most money while doing the least amount of work, then try naming a profession that meets the criteria as well as voice-over acting. Where’s the “labor,” really? Someone hands you a piece of paper with some words on it, you step up to a microphone and read them with a little pizzazz, and presto! You’ve just made many thousands of dollars, potentially six figures. And your voice might be heard on commercials or audiobooks or TV for years, during which time you keep getting checks in the mail, all for showing up to read out loud for half an hour.

This perception of voice-over acting — or VO, as people in the biz refer to it — is partly due to the tall tales voice actors tell about their careers. Take Morgan Lavenstein, a local actress who makes her living primarily from VO. Lavenstein is in her mid-30s, has a raspy East Coast voice, and talks like Kirstie Alley if she were from Baltimore; she’s the kind of person you could imagine as a wiseass girl at a Jewish summer camp.

It was 2012, as Lavenstein recalls, and she had just moved to New York City after college to try to make it as an actress. To support herself, she bartended. “I had these regulars who worked right across the street that were commercial editors,” she says. “They’re like four dudes in their 50s. We got along like gangbusters. And they were like, ‘You have a great voice. We should use you on a scratch.’ And I was like, ‘What the hell’s that?’ And they said, ‘It’s like a demo, the first voice that the client hears.’ ”

Lavenstein recorded the scratch tape — an ad for Glade air fresheners — on her phone while she was on vacation, not thinking much of it. Even though Lavenstein recalls one of the editors describing the recording as “ratchet,” the client, SC Johnson, which makes Glade, loved her voice. After a formal, un-ratchet session at a recording studio, she booked it. “It was a huge, crazy rebranding, a new national campaign,” Lavenstein says. “And I went in all the time. There were several spots, some online, but there were at least four national television spots.”

The Glade campaign ran for two years. “I started getting the checks, and I’ll never forget, my roommate at the time was like, ‘Holy shit, we won the lottery!’ ” Lavenstein cackles. “He texts me a picture of our entire coffee table covered in checks, from $20 to $5,000.” In all, she estimates that she received $200,000.

Nine years later, Lavenstein semi-regularly performs onstage and on camera (like many local actors, she’s been on Chicago P.D. and Chicago Med), but she draws the closest thing to an annual salary from VO. She’s been the voice of Poise Impressa bladder support devices, the Dyson Lightcycle desk lamp, and Cleveland Clinic. You know that ad for Redd’s apple ale with the tagline “There’s wicked within”? That’s Lavenstein.

If VO were so easy, everyone would do it, of course. And not everyone can. But with every year, more and more people think they can. It’s the fastest-growing minor at Columbia College Chicago, says Deb Doetzer, who teaches in the school’s voice-over program, which is part of its communication department: “It’s skyrocketed.”

Doetzer, who wears azure cat-eye glasses and converses like a supercut of Nickelodeon shows, estimates that of all her students, just 20 to 30 percent go on to do significant work in voice-over. But that proportion doesn’t seem bad, right? Not everybody can look like Timothée Chalamet, move like Jim Carrey, or act like Cate Blanchett. Some people, though, might be able to sound like them. And even though work on video games and animation is centered in L.A. — where the boom in the industry has largely taken place — it’s possible to make a career of VO without leaving town. Chicago has long been a hub of the advertising industry, and the voicing of commercials remains a vibrant enterprise here, making a few people quite rich. Those who know how to work their larynx, that is.

You should know, my motives are selfish. While I’ve been told I resemble Tom Hardy (and maybe I could have had a career as his out-of-shape stunt double), it’s my gloriously resonant baritone that I’m more often informed is going to waste. “You know, you have a great voice,” people have said to me, out of nowhere, typically right after they point out how much I look like Tom Hardy. For years, I’ve done impressions of my friends, broken out in random dialects, imitated DMX’s rapping style, and concocted characters with funny voices (most famously, my 1940s Movie Studio Pitch Guy). Maybe I should have tried my hand at comedy, but at 40, it’s probably too late for that, so I might as well cash in on these pipes.

I asked actor friends of mine how to get started in VO, and they all told me to take a class at Acting Studio Chicago. So at the beginning of 2020, I pulled $450 out of my savings and enrolled in Beginning Voiceover. On the first day of class at ASC’s River North location, the instructor introduced himself by announcing, “Hi, I’m Dave Leffel. I’ve got a glass eye, one ball, and let me tell you how I made six figures in 45 minutes.”

Leffel, a goateed man in his 50s who looks a little like Sal Governale from The Howard Stern Show, proceeded to recount an anecdote he’d obviously recited dozens of times before: He walked into a recording studio, and the creative director and engineer asked him to read out loud “Anheuser-Busch, St. Louis, Missouri.” They requested he say it again with a slightly different inflection. “That’s great,” they said. “Now do it the same way, but for multiple other cities all across America: ‘Anheuser-Busch, Denver, Colorado’; ‘Anheuser-Busch, Atlanta, Georgia.’ ” The tag played on radio spots for more than a year, and Leffel received enough in residuals to redo the siding on his house.

The eye? Lost in a childhood accident. The ball? Testicular cancer. Both of which were, apparently, secondary to the Budweiser commercials.

Later in the class, Leffel played us his demo reel through a stereo amp. Ten seconds in, I laughed out loud from shock. His reel paralleled the feeling of flipping the FM dial while every station was on a commercial break, a virtual catalog of VO ad styles. There’s chipper and boyish (Temptations cat treats), butch and gristly (Banquet Mega Bowls frozen meals), evenhanded and conversational (Fiat), and a tender stage whisper (the tag goes “Life is a journey, there’s a starting point, and an ending point,” with Leffel pausing semi-dramatically after each comma).

The minute-long reel achieved its intended effect: Right away, you knew Leffel was a pro, versatile enough to tackle any kind of radio spot. One student asked Leffel about the reel’s final read, and Leffel called it the “talking to my baby” voice. He lifted his hand, looked at it as if it were a newborn, and spoke gently, in the same style as in the spot: “My baby. My sweet, tiny baby. I love you, my little baby.”

For the next session, Leffel asked us to take a print ad and read the copy as if for a VO spot. I ripped a page out of this very magazine, a Rolex ad from the February 2020 issue. With my incomparable baritone, I’d for sure nail the suave refinement of lines like “The world of Rolex is filled with stories of perpetual excellence.” I stepped up to a lectern and started reciting the text for the class. But halfway through, Leffel began to pelt me with criticisms, each time telling me to take it from the top. I was too loud. I was reading too slowly. I was putting on airs. I didn’t sound like a real person. OK, now I sounded like a real person, but I’d lost the flavor of the copy. Well, there go my chances of becoming a voice actor, I thought. I suck.

After class, I asked Leffel about my read, and he generously spoke with me about the intricacies of VO. The first instinct might not be the best one, he said, and a lot of VO is about approaching copy from multiple angles, rehearsing each one, and then finding out which rendition is going to stand out and fit best for the ad. He told me not to worry; I was just starting, and no one nails it right away. The next class would meet in a professional recording studio, and he’d email me the ads ahead of time so I could practice. The date of the next class: March 11, 2020.

When the COVID-19 pandemic shutdown began, ASC offered to continue our class over Zoom, but I opted to withdraw; for $450, I wanted to wait until I could learn VO in a studio. Later, I would realize I’d made a huge mistake. The pandemic accelerated a number of changes already underway in VO. And the biggest one, which defines the business today: Almost everybody is doing it from home.

So if you want to get into the industry, you also have to learn a little about how to be a DIY audio engineer. And you’ll have to make an initial investment. In VO, you can’t avoid having to spend money to make money, though these days you don’t have to spend quite as much as you did in the past.

“When I signed in the early ’90s, my agents were like, ‘OK, your demo’s fine, but we want you to do a commercial section, a narration section, a character section, and a promo and trailer section,” Doetzer recalls. “So to do four sections, there was only one person in town who was producing voice-over demos. Each one of those sections cost $2,500.”

You can construct a reasonably good home studio for less than the price of one of those sections. If you have a laptop or desktop computer, you’re already halfway there. Most people, even VO actors, will tell you a Blue Yeti microphone, which sells for $130 on Amazon and resembles what podcasters use, is perfectly fine if you’re just starting out. “At the end of the day, nobody knows if you’re on a Neumann U 87 or on a Blue Yeti,” says Doetzer. (New models of a Neumann U 87 Ai go for upward of $3,000.) But a Blue Yeti is a USB mic, and some sound engineers and casting directors can hear the difference between that and a proper condenser microphone.

Every step up inevitably improves the sound quality, and even a marginal upgrade can make a significant difference in your ability to land gigs. Lavenstein uses a Røde NT1, which retails for $269 and comes with a pop filter, a circular screen positioned a couple of inches in front of the microphone that helps to eliminate the sounds of spittle, tongue clicking, and lip smacking. The Stedman PS101 Proscreen is a widely recommended pop filter that runs about $45, but Doetzer says there are perfectly fine ones that can be found on Amazon for 10 bucks.

After that, you’ll need a closet or an enclosed room, though even the smallest spaces tend to insufficiently deaden sound enough for a proper recording. Worry not. For as little as $200, you can assemble a vocal booth using PVC piping, soundproofing blankets, and acoustic foam panels.

Jacki Hydock, who like many VO actors is coy about her age (“you can totally include an age range of 25 to 35”), started as a print model and on-camera actress and has since launched a steady career doing VO. She puts her initial investment in a home studio at around $300. “My podcast microphone was 200 bucks,” she says. “The sound panels — maybe 24 of them on Amazon for like $35. Then a carpet, depending on what your space is — let’s say a pantry — is like $60. And I already had some Beats headphones.” Hydock’s matter-of-fact, bouncily delivered rundown exudes a hustler’s mentality, undaunted by naysaying. “I didn’t go to med school. You can get your questions answered on YouTube.”

That said, Hydock believes that the more you invest, the bigger the payoff. When I interviewed Donna Jay Fulks, a longtime Chicago VO actress now based in Los Angeles, via a video call, she appeared onscreen in an in-home standalone recording booth covered in foam panels. “Now I’m an engineer,” she says. “I had a super-fun video game session: I’m doing all these different scenarios, and I’m turning down the gain on my mic so that I’m not peaking when I’m yelling while being stabbed to death. I’m doing all these adjustments myself that I wouldn’t have been trusted to do before the pandemic.”

Fulks ballparks her home setup at $20,000. She uses a Mac Mini (because it’s “real quiet,” she says), a Sennheiser shotgun microphone for commercials and announcing, and a separate Neumann for video games and animation.

Fulks talks the way Christine McVie sang, in a warm and gentle alto that feels like dusky sunshine on blond wood. Animation work is what lured her to L.A. after close to three decades as a successful commercial VO actress here. In Chicago, she spent many years as the voice of Oprah Winfrey’s network, OWN, and a decade doing campaigns for J.C. Penney.

But she had always wanted to work in animation, and that just wasn’t feasible in Chicago. “Within five miles of me, there are 50 recording studios,” Fulks, who is married to singer Robbie Fulks, says of her new home. She voiced Longclaw in the Sonic the Hedgehog movies. “I had to go to Paramount a lot and get in there and record. They’re not recording anybody from home for something like that.”

How do you become the voice of J.C. Penney and OWN? First, it’s important to know what advertisers are looking for. Ashley Geisheker, who’s the head of production at Leo Burnett, has been casting VO work for more than a decade. She’s cheerful and bubbly, like a precocious child, despite holding the fate of thousands of voice actors in her vintage-Rolex-spinning hands. Once her agency sells a client on a campaign, she says, “it’s our job to dial in what sort of character, age, voice performance, texture, and tone we want to build.”

Though creatives do their best to convey what they’re seeking, voice actors tend to snicker at the descriptions. “Scarlett Johansson type, female, warm, inviting, feels like a real person, not an announcer,” Lavenstein says, mocking the casting specs she sees. “Would love someone with a distinct and memorable texture to her voice — huskiness, but shouldn’t sound sick, nasally.” Having read a number of specs for VO spots, I can assure you this isn’t much of an exaggeration.

One reason the descriptions sound so oddly specific yet still loose is that casting directors want to allow for actors to bring something of their own to the spot. “We will sometimes layer in performance notes: ‘We want this to be incredibly energetic, or we’re looking for something a little bit more solemn,’ ” Geisheker says. “If we do it too broad, it doesn’t give the actors enough to go on, but we want to give them enough room to interpret it and give it their own persona when they audition.”

“People will just come into our office and ask, ‘How do I get into this?’ ” says NV Talent founder Debby Kotzen. “Do you walk into a doctor’s office and ask how to be a brain surgeon?

Sometimes, agencies might have a specific actor in mind, whether it’s someone local or a celebrity (she says Bryan Cranston, who provided VO on a Hillshire Farm ad, is a “wonderful, delightful person”). But for the most part, casting directors will send the specs to talent agents, who each return roughly 10 auditions back to them, totaling around 200 that Geisheker and her team will review. They will then select four to six, present those to the client, and collectively decide.

What qualities make for a winning audition? “It’s really a gut thing,” Geisheker says. “It’s hard to put into tangible terms what I’m looking for. If it evokes some sort of emotion from you, that’s usually what rises to the top.”

Geisheker estimates she books local actors on 40 percent of VO jobs. She prefers people with an improv background. “The way they can take the script and riff, play off the creatives and the studio engineer working with them — you need someone who’s really quick-witted and willing to play. That helps elevate the creativity and take it to a place nobody had thought of.”

Doetzer has a background in improv, and Fulks took classes at iO when she first started to consider roles in animation. Almost every performer I spoke to had acted onstage or onscreen before gravitating toward VO.

In Chicago, there’s a Big Four when it comes to VO agencies: Gray Talent Group, Grossman & Jack, NV, and Stewart. Of those, NV stands out for emphasizing VO in particular (the company used to be called Naked Voices). Its founder, Debby Kotzen, was once employed by this magazine as the director of classified advertising before becoming a talent agent and then striking out on her own by starting NV Talent in 2000.

“I always had a good ear for things,” she says. “One of the first people I took on for voice-over booked a major national campaign for Gatorade. Remember ‘Gatorade: Is it in you?’ After that, I’m like, I obviously have an aptitude for this.”

Kotzen runs NV with Mary Kay O’Connor, who joined in 2014. Ironically, neither has a voice particularly suited for the craft (Kotzen says hers sounds like the teacher in Peanuts cartoons, and she’s not entirely wrong). In the present market, they book around 10 to 15 percent of the jobs for which they are asked to provide auditions, which is impressive given that they’re competing against agencies from across the country.

NV represents more than 200 VO actors, but that’s a small roster when you consider the number of submissions the agency receives. In the first year of the pandemic, O’Connor estimates, she listened to 600 demos from aspiring VO performers. She and Kotzen dutifully catalog every demo in a binder, regardless of whether they take on the performer as a client. “Some women will call and say, ‘Hi, my husband has a good voice. I wanted to get him an agent for his birthday,’ ” Kotzen says, adding: “People will just come into our office and ask, ‘How do I get into this?’ Do you walk into a doctor’s office and ask how to be a brain surgeon?”

In potential signees, they look for an understanding of technique. “It’s 90 percent how you use your voice and 10 percent how your voice actually sounds,” says O’Connor. “It’s all about interpretation, how you can bring a script to life. It’s a very particular muscle that a lot of people have to learn.”

Kotzen and O’Connor don’t just sit back and field submissions, of course. They scout potential talent by going to see improv and theater shows. (They also represent on-camera work.) “We look for someone with an easy-to-understand voice — no mumbling or sibilant s — who has a good range,” says Kotzen.

Virtually everyone I spoke with rolled their eyes about people who think it’s easy to get into this line of work. Fulks waved her hands in the air, mimicking a ditz: “Everyone tells me I have a great voice!” Each time I heard a quip like that from a professional, a little part of me died. But I also understood their frustration with the notion that VO doesn’t require any real skill or effort.

“You really can’t teach someone to be talented,” Doetzer says. “But then there’s also the technical part of it: getting it to time, taking a beat after a certain word to let it land on the listener’s ear. There’s always people who just work really hard and get better, and they tend to make it.”

the photo of the Chicago voice-over actor to the classic advertising line you think they spoke. (Click the play button in the box to hear the line.) If you are correct, the photo will lock into place.

Congratulations! You have completed the quiz.

Photography: (Berman) Shani Hadjian; (Cerny) Antonio Perez/Chicago Tribune; (Fulks) Cathryn Farnsworth; (Henzel) Popio-Stumpf Photography; (Hogan, Ronge) Brian McConkey Photography; (Nagraj) Ian McLaren; (Stacker) Pete Stacker; (Whittington) NV Talent

In February 2022, I cashed in my ASC credit to take another shot at Beginning Voiceover. My instructor this time was Brad Grusnick, an actor who specializes in voicing video games and animation; he’s been the voice of Magnus Finke in Dragons: Rescue Riders and of more than 30 characters in The Elder Scrolls. He’s around 40, with a shaved head, a ginger beard, and the booming tenor of an excited theater kid (he has a bachelor’s in theater from Northwestern).

Five of our classes were virtual, but three took place at the Chicago Recording Company’s state-of-the-art facility in Streeterville, where voice actors typically read for huge ad campaigns. (It’s also where Chance the Rapper recorded Coloring Book.) One at a time, we’d enter the recording booth, remove our masks, and read the ads Grusnick gave us. An engineer was on hand to record, edit, and wipe down the mic and stands between reads.

From the start, Grusnick made it clear that classes at ASC probably wouldn’t suffice if we wanted to make a living doing VO; he implored us to sign up for an improv class. A common refrain: “The biggest thing that any professional voice actor will tell you is that it is acting. It is small-v, big-A acting. If you have no experience acting, take an acting class. Learn how to analyze texts, look at scripts, hit emotional moments with your fellow scene partner.”

Occasionally, if a student read flatly, Grusnick would barge into the booth to deliver his critiques. Nine times out of 10, his criticism concerned his most valuable instruction: Voice acting is physical. For example, the first tip he gave us was to always stay hydrated. The worst way to read ad copy is with cotton mouth. Other suggestions were technical, like how the distance between you and the mic should be measured from the tip of your thumb to the tip of your outstretched pinkie. He demonstrated how standing up and keeping your chest straight will promote the clearest and most sonorous voice, how sitting down can compress your diaphragm.

One of my classmates was Dominick, a bespectacled and goateed man in his early 30s. He had a buttery baritone, but his reads were almost always rushed and deflated. For the last spot — Golden Corral’s new “country-style” lunch — Grusnick directed Dominick to smile the entire time he was reading. This slight physical change had an astonishing effect: His performance was probably the best I’d heard in the entire eight weeks of the workshop.

Months after the class ended, when I was interviewing Grusnick for this story, I asked him what he remembered about my readings. “You had fantastic energy,” he told me. “You started off having a little bit of a commercial read to you, which happens a lot. And when I say ‘commercial,’ I mean we have this idea in our head of what a commercial is supposed to sound like. And as the weeks went on, you relaxed that attitude, because, really, all commercials are is you having a conversation with a friend, and you’re telling your friend, who happens to be on the other side of the screen, about this great thing that you just discovered.”

“The biggest thing that any professional voice actor will tell you is that it is acting,” says instructor Brad Grusnick. “It is small-v, big-A acting.”

My interest in VO stems to some degree from my adoration of Phil Hartman, who was an in-demand voice actor in commercials and animation even before he joined Saturday Night Live. His gliding, operatic tenor was the voice for the sleazy attorney Lionel Hutz and the arrogant movie star Troy McClure on The Simpsons and could be heard on almost every voice-over on SNL. But today, trying to mimic him or Charlton Heston or Katharine Hepburn is the worst possible strategy for breaking into VO. The first thing teachers will tell you is to “sound like a regular person.”

Casting directors want “someone that doesn’t sound like an announcer,” O’Connor says. “They want someone with the least amount of polish. Unpolished voice-over is what’s on trend right now. There was vocal fry; now people don’t want vocal fry. They just want human-sounding.”

Of course, this presents a paradox: If you’re supposed to sound like yourself but your voice isn’t actually what advertisers want, what then?

“I think it’s a matter of finding your own truth in the story and giving it your special sauce, not trying to be someone else or what you think you should sound like,” Doetzer says. “My students often go, ‘It all sounds kind of the same to me.’ Well, you’re going to do a Mamet play very differently than you’re going to do Shakespeare. When you listen to a commercial, think about how you would do it, but pay attention to the timing and the way the words are delivered and what pops and what doesn’t.”

On the last day of the ASC class, we met over Zoom, and Grusnick gave us tips on our home setups and provided agency contacts and reference sites. He asked us if we had any more questions. I had one: Was there a rock star of VO? Was there anyone in Chicago who was the king or queen of the biz? Grusnick thought for a bit and said that currently the playing field was pretty level, with no real standouts. “I mean, there isn’t a Harlan Hogan or anything like that.”

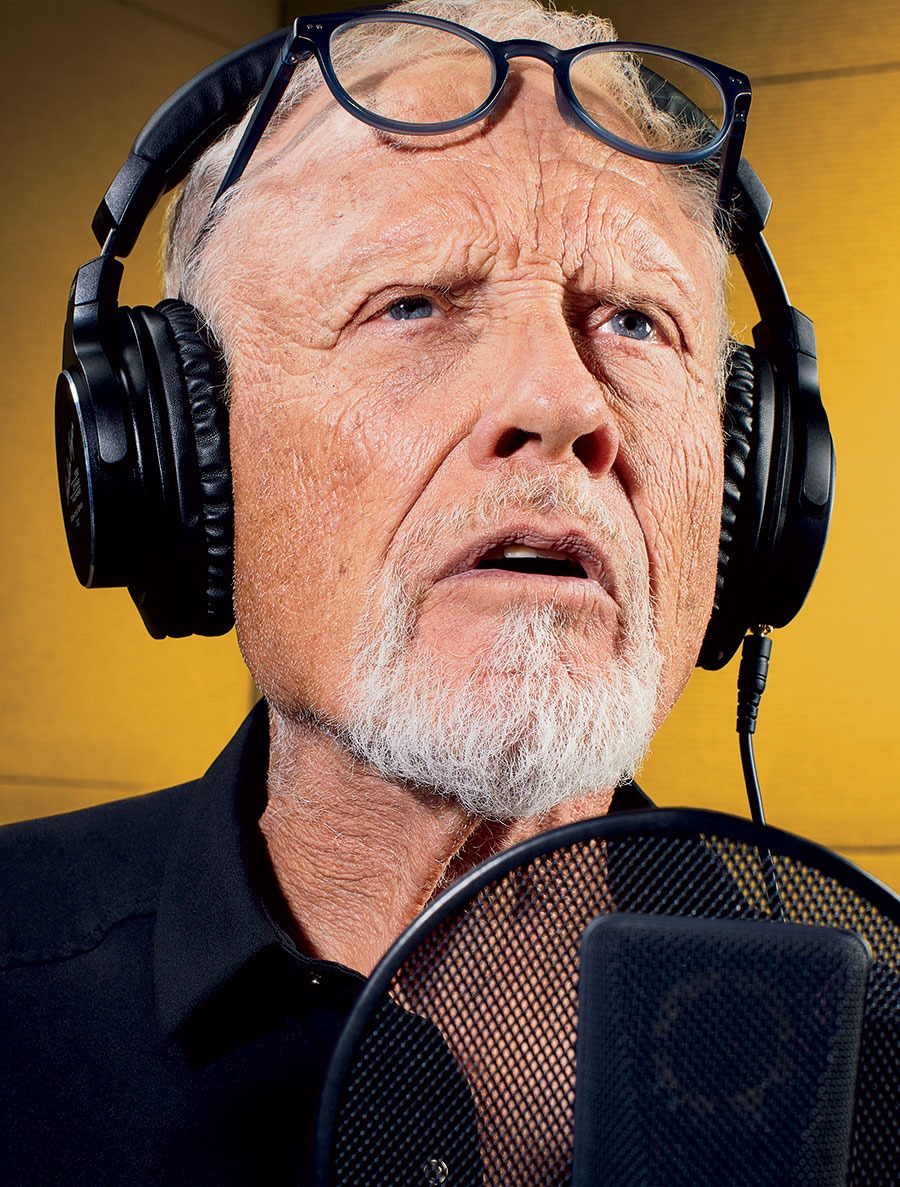

What’s the story about?” Harlan Hogan is speaking rhetorically, but he’s also telling me the most important question to ask yourself when you get a script. We’re standing a bit awkwardly in a WhisperRoom recording booth in his home office, almost as if I’m looming in the doorway of a high-tech port-a-potty. It’s roughly four by four by seven feet, and for the past quarter century, this closet-like compartment is where Hogan has worked.

Hogan, 76, has a shock of white hair, a closely cropped beard, and oceanic blue eyes. He’s lithe and agile for his age, padding around gracefully in wool slippers and zip-away hiking pants. His voice is the macho purr of commerce, a gently leonine growl that conveys ease and fatherly compassion. When he talks, you can hear shampoo, beer, cereal, health insurance, and super PACs. Hogan has read spots for all of them. One time, he voiced a dozen commercials in a single day. He’s unquestionably one of the most recognizable and successful Chicago voice actors in the medium’s history.

On this early July day, Hogan is reviewing voice-over narration he recorded for a short documentary honoring Milt Larsen, the recently deceased founder of the Magic Castle, a secretive and exclusive clubhouse for magicians in L.A. Hogan, obsessed with magic since childhood, has an elaborate showroom of thaumaturgical memorabilia in his basement, and his house is adorned by vintage magic posters. The short played during the Academy of Magical Arts’ annual awards show in Los Angeles. Hogan has been a member of the Magic Castle for 44 years, and producers comped his airfare and tickets to the black-tie event.

He brings up the job to demonstrate how he approaches his work. When he got the script, he started by invoking his first rule: Try to analyze the story. “I address these things as a play. So I read the first few things, and I said to the producer, ‘Yes, it’s a documentary with facts. But to me, it’s a love story.’ ” The producer enthusiastically agreed.

Hogan keeps three microphones in his booth, and for this narration he decided on a Sennheiser MKH 416 shotgun mic, which looks like a long black cigar. “They were originally designed for location recording,” he says. “If you’re a person who moves around, it’s not a good mic, but I use it a lot on things that are just a little edgier.” The 416 is particularly sensitive to noise, so Hogan demonstrates how he voiced the script gently, and with a slight gristle, exactly like someone reading a love letter out loud.

All this is happening in Hogan’s mansion in North Barrington, where he lives with his wife, Lesley, who used to be his agent. “My corny voice-over joke” — Hogan has many corny voice-over jokes — “I had to marry my agent because it’s the only way she’d return my calls.” The house is white clapboard, with a three-car garage and a long porch lined with pots of bright purple flowers. Hogan and his wife also own a sailboat and two horses, not to mention a motorcycle (he is a card-carrying member of the Iron Butt Association, signifying he once rode more than 1,000 miles in 24 hours).

Hogan’s home office is the size of a studio apartment, dotted with memorabilia like vintage microphones and a still-operational wire recorder from the 1940s. Next to his booth is a desktop computer, a mixing console, and speakers for him to hear playbacks of his recordings. After Hogan does his reads, he’ll do a light edit before sending it off to the engineer. He likes to do his takes in “trips,” offering three options.

As he plays me the version of the documentary voice-over that the producers selected, I notice a particular twist in one line. “The castle property is filled with skewed architectural pieces from all over the world,” Hogan intones, “including vintage stained glass, old wood paneling, and whatever Milt found interesting.” Hogan had added a pause between “whatever Milt” and “found interesting,” articulating a sly wink to Larsen’s eccentricities. I asked him how he came up with that, and he explained that sometimes you have to visualize what you’re saying and consider how to re-create that image in speech.

Harlan Hogan’s voice is the macho purr of commerce, a gently leonine growl that conveys ease and fatherly compassion. When he talks, you can hear shampoo, beer, cereal, health insurance, and super PACs.

A native of south suburban Lansing, Hogan studied theater at Illinois Wesleyan University, then headed straight to Chicago, where he bounced around, working in radio (“It’s pretty much the same thing: ‘Time and temperature, cooler near the lake, we’ll be right back with Sonny and Cher’ ”) and dinner theater (“Peaches Pancake House and Dinner Theater; think of buying pancakes with The Odd Couple”) and as a salesman for Honeywell (“Of course we all know that a BFA in theater is just the training you need to sell computers”).

The Honeywell job is what led to Hogan’s first big break. In the mid-1970s, his agent set him up with an audition for the accounting giant Arthur Andersen, as a narrator for corporate training videos. “They hand me a bunch of pages, and it’s all about computers,” Hogan says. “So I’m reading a book on how to take care of your systems analyst. And I rambled on and on, and they said, ‘We’re flabbergasted! We’ve seen like 20 people today, and nobody knew how to pronounce all this stuff. I can tell you right now, we have a lot of videos for you to do.’ ” Hogan performed in more than 100. “Pure dumb luck. I was bringing in more money than when I was in sales.”

Hogan knew the Arthur Andersen gig wouldn’t last forever, so he got a part-time job as a disc jockey at WCLR, which at the time was an easy-listening station. He used the radio station to produce his demos and soon began finding lucrative opportunities in VO work. “I could do numerous commercials versus maybe one on-camera every six months if you’re lucky, and we all know theater doesn’t pay squat. One person who had been in the business told me, ‘Oh, Harlan, I don’t think you should do that, they’ll typecast you.’ Well, there’s two words there: ‘Type’ I don’t care about, but ‘casting’ sounds real good.”

Up until the late 1970s, advertisers wanted cartoonish voice acting, and there were Chicago performers who happily obliged, like Larry Moran, a.k.a. the Funny Voice Man, who played Cap’n Crunch, Mr. Monopoly, and McDonald’s Grimace. Or they sought people with unique deliveries, like James C. Dolan, who cofounded Streeterville Studios here and boasted a deep baritone that was ubiquitous on the airwaves. But advertising was entering a transitional period where the traditional disc jockey sound was losing favor to a more conversational style.

Hogan singles out Joel Cory, a retired Chicago VO luminary now living in Florida, as every agency’s first choice, a “vocal chameleon” who long played Pop from the famous Rice Krispies trio. In the ’80s, Hogan and Cory were part of a crew of legendary local voice actors, many still performing today, like Tim Dadabo, Jeff Lupetin, and Pete Stacker. In my conversations with voice actors, Stacker’s name came up often. When you hear his rumbling, looping bass voice, you can quickly place it in everything from Comedy Central promos and big Budweiser campaigns to the video game Halo and the Hot Tub Time Machine trailer. He is so closely correlated with “the movie trailer voice” that Saturday Night Live used him for a movie trailer parody in 2015.

In the ’80s, Hogan and other voice actors would hang out at the Boul-Mich Lounge, a burger and dive bar at Michigan and Grand Avenues in the Near North Side, because it had a direct line to Marietta’s Answering Service, where performers would get calls from talent and ad agencies. “You always wanted the bartender to say, ‘Hey, Harlan, it’s Service.’ ”

This was during what Hogan refers to as the “golden age” of VO in Chicago. In those days, advertisers had limited outlets: newspapers, magazines, billboards, radio, and broadcast TV. That meant they would shell out top dollar for this precious real estate. Voice actors got paid not only for their performance of a spot, but in residuals every time that spot played. If you landed a gig for a network TV ad, you might ultimately wind up with a six-figure payday for less than a day’s work.

Back then, the agencies were consolidated in two places: New York City and Chicago. Madison Avenue had plenty of actors to choose from in New York, but the talent pool here didn’t run all that deep. If you were lucky enough to break into voice acting in Chicago, there was plenty of work. Hogan remembers reminding himself how good he had it. He’d think: “I recorded this line — ‘Raid. Kills bugs fast’ — three years ago and they’re still paying me.” When he was profiled in the Tribune in 1999, Hogan was still booking multiple sessions a day, commanding $350 to $425 an hour.

He pauses, turns his head to the side, and looks out the window of his office. “It was miraculous. And you knew it couldn’t last forever.”

Ilyssa Fradin has soft features and chipmunk eyes, but when she speaks, you hear plumes of elegant cigarette smoke that could have been exhaled by Barbara Stanwyck or Linda Fiorentino. Like Doetzer, Fulks, and Leffel, Fradin was part of a new wave of voice actors who entered the Chicago market in the early ’90s. “It was a great time,” she says. “There wasn’t the internet and you actually had human connection.”

Fradin came from Indiana University to do off-Loop theater and got a job at Starbucks. All her coworkers were actors as well. One of them asked her if she’d ever thought of doing voice-over. “I said, ‘OK, what is it?’ I auditioned for an agency by reading some copy, the agent was like, ‘I like your sound, and I’ll sign you.’ ” Fradin booked her first audition, a national campaign for Betty Crocker.

But there were already signs that the industry was changing. “As time’s gone on, you have way more platforms distributing content that comes with advertising,” Fradin says. “That all started when cable came along.” Companies discovered that by spreading their ads across several channels, they could create the same exposure as a network campaign while navigating around stringent and costly union guidelines.

That’s only increased with the ascendancy of the internet — YouTube, online radio, social media, and streaming. As Debby Kotzen explains, if an advertiser doesn’t sign a contract agreeing to use SAG-AFTRA voice actors, then it’s not required to pay union wages. “On a national TV spot, you can make anywhere, depending if it’s seasonal or situational, from $50,000 to $250,000 — if it’s a union job,” she says. “We see nonunion jobs for national products that pay $3,000.” And with those, there are no residuals.

Ultimately, though, the internet’s biggest disruption to voice acting has been by doing what it does best: spread information. “Voice acting used to be an anonymous thing, the secret magic part of acting where nobody knows I’m doing it and I make all this money,” Grusnick says. “But now, because of social media and everything else, people will aspire just to be voice actors. And because you can record stuff at home and you don’t need a crazy expensive microphone, the market has become flooded with people who aspire to do this.”

To book lucrative spots — the ones that require joining SAG-AFTRA — you almost always need representation. And only a fraction of aspiring voice actors are able to secure an agent. Services such as Voices.com and Voice123 have emerged in recent years to bypass that process, asking you to submit a membership fee in tiers between $200 and $600 annually to access direct listings from advertisers.

Most VO actors sneer at those pay-to-play services, and they have even worse things to say about Fiverr, an online marketplace similar to Upwork where freelancers bid on work (Hogan calls it “absolutely obscene on all counts”). But when Jacki Hydock was just getting started, Fiverr was the main place the voice actress could secure gigs. “I made a profile and my prices were dirt cheap, like $10 for every 50 words,” she says. “Someone once hired me to say a happy-birthday greeting like Katy Perry. Ultimately, it was just to get myself noticed. Then people leave me five-star reviews, and that started popping me up. All the while, I’m constantly improving my sound quality, my microphone, my reel, so then I can start charging more.” Hydock, who finally booked a union job last year, calculates she was making $100,000 a year through Fiverr.

As with anything these days, there’s also the issue of AI. Most voice actors responded with mild panic when asked how it might further erode the industry. Doetzer says one of her clients asked her if she would like to “continue in perpetuity” — meaning have her voiceprint used even after she dies. “ ‘Perpetuity’ is a word you never want to hear as a voice actor. My agent was like, ‘What do you think?’ I’m like, ‘This is forever! I’ll be six feet under and my voice is still out there.’ You don’t want to say, ‘I’m worth $80 million, bitch,’ but give me the money.” SAG-AFTRA has already enacted rules about the use of digital doubles in its last contract.

It’s extremely difficult to make a good living in voice acting here these days. I was stunned when Grusnick told me that he doesn’t book enough work — around $30,000 year — to do it full-time. “Once you take out taxes and business expenses and agency fees, it’s about half of that.” He also works part-time scheduling for a construction company and teaches VO to doofuses like me.

Diversifying helps. These days, Hogan’s bread and butter is political ads (he narrated spots for Kyrsten Sinema’s 2018 U.S. Senate campaign in Arizona and, more recently, for the Wisconsin Supreme Court race). During one three-month stretch of the 2008 presidential election season, he performed in 236 political commercials. And he isn’t exclusive to one party. “You don’t have to vote for these people,” he says. “Most actors will tell you the fun acting is playing the villain.”

Says Doetzer: “I tell my students, ‘You have to be versatile.’ I also teach a narration class, where we cover audiobook narration, corporate stuff, e-learning, training videos, and IVRS [interactive voice response system]. I’ve been the female voice of Emmi Solutions since 2005. I have a little income coming in every month, and I get to work from home. I don’t have to wear pants!”

ASC offers Intermediate Voiceover for people who’ve taken the beginners’ course, and I decided to enroll for spring 2022. In the class with Grusnick, I’d had about a dozen classmates. For intermediate, there were half that, and the talent was noticeably better. I was particularly in awe of Cara, a middle-aged copy editor from Wheaton whose crystalline voice could convince me to buy pharmaceuticals.

My instructor was Jeff Lupetin, who took a different tack than Grusnick. Lupetin encouraged me to experiment with different voices, but to harness them so they could be useful in ads. He especially enjoyed one of my guises, a leathery rasp that was my loose imitation of the actor Will Arnett. It sounded particularly fitting for a commercial exercise promoting a new roller coaster at Kings Dominion, an amusement park in Virginia.

For an additional $2,100, I took four private sessions with Lupetin and produced a demo at Bam Studios in River North, recorded by Leffel, who’s also an audio engineer. I hadn’t seen or spoken to Leffel since the pandemic, and he seemed surprised by how much I’d improved. Though we had scheduled an hour, we recorded eight spots in half that time. I asked Leffel if he’d be open to us recording a tag for a car commercial — the wrap-up, fine-print information you hear at the end of a spot. During my class with Lupetin, we discovered that if I spoke in a “golf announcer whisper,” it would be perfect for tags. So we added one: “Place your custom order and lock in 3.9 percent APR financing for 60 months on select Ford vehicles and you’re protected.”

Only 48 hours later, Leffel sent me back my minute-long demo. It sounded great, better than I’d expected, and I sent it around to a few people, including Lavenstein. Impressed by my demo, she arranged an audition for me with Stewart Talent. In April, I went to their offices in the Wrigley Building on Michigan Avenue to see if they’d represent me.

A woman greeted me and accompanied me to a recording booth, where she presented me with copy for three ads. She gave me 10 minutes to review it, then returned and told me to read the copy as straightforwardly as possible, informing me that the two women who head the VO department would be listening in. After each of the three reads, she told me that I had done well and didn’t need another take. As we exited the room, I was on cloud nine — I was about to be represented by one of the top agencies in town. Someday, I thought, I would look back at this moment as the beginning of my new career. The woman said she only needed to discuss the audition with the VO heads and would be right back.

I sat and waited for roughly one minute before she returned with a downcast look. They thought I needed to take more classes. Well, I said, I’d already taken quite a few, and they’d heard my demo. Was there anything I could have done differently? Ultimately, she said, they already had too many actors who sounded like me. Maybe, she added, I should try somewhere else, for people just starting out.

When I returned home, I told my wife what happened, and how weird it was to be complimented and think I’d done a good job, only to be rejected. My wife, who majored in theater in college, widened her eyes, spread her arms, and said, “Welcome to acting!”