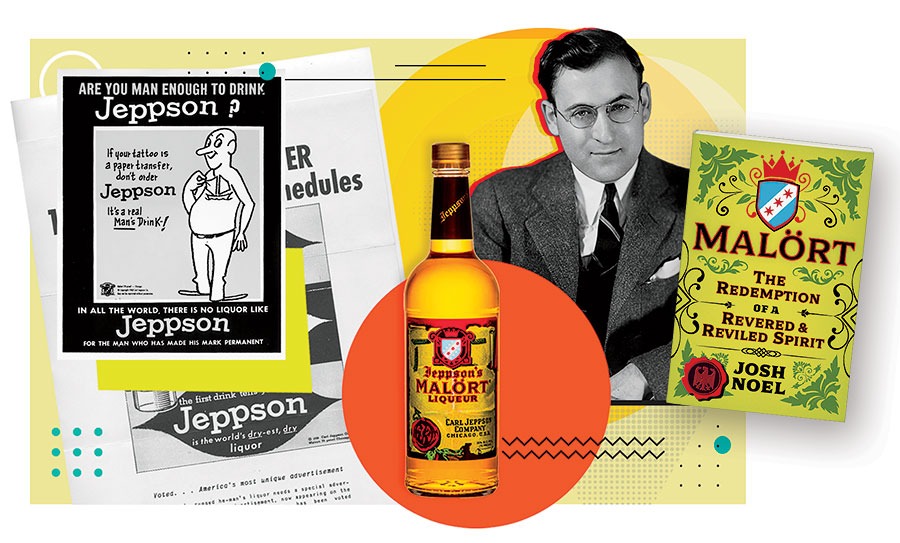

1 Malört’s original owner was a draft-dodging ex-convict.

George Brode (pictured above) had a past as interesting as the taste of the spirit he promoted, according to Noel’s Malört: The Redemption of a Revered & Reviled Spirit. A lawyer, Brode owned stakes in a series of distilleries in the years leading up to World War II. He purchased the spirit’s formula from Carl Jeppson, a Swedish door-to-door salesman, in 1934. But after the war, Brode was convicted of misrepresenting his role in his businesses to avoid military service.

2 For many years, Malört was a virtually one-person operation.

After prison, Brode sold his distillery interests — but kept Malört, selling it one case at a time for more than 30 years. After his death in 1999, his secretary and longtime partner, Pat Gabelick, ran the operation. By the late ’90s, Malört was on the verge of going out of business due to lack of demand.

3 Malört was sold as a manly drink.

The early marketing was steeped in masculine stereotypes. Brode advertised it as a liquor a “panty-waist” couldn’t drink and a “he-man’s prerogative,” asking, “Do you wear a beret because it becomes you?” If so, Malört was not your drink.

4 For a large portion of its life, Malört wasn’t made in Chicago.

In 1989, when the local distiller that crafted Malört was sold, Brode moved production to Florida. Though much of the initial boom in Malört’s popularity in the early 2000s was driven by its identity as Chicago’s hometown spirit, production didn’t shift back until 2018, when Pilsen’s CH Distillery bought the brand from Gabelick.

5 Social media and dedicated bartenders kept Malört alive.

Malört sales were minuscule until Twitter and TikTok and the like (remember the photos and videos of “Malört face”?) thrust it into the trendy spotlight. Malört’s rise is also the story of the rise of craft cocktails in Chicago, as some famous local bartenders, including the Whistler’s Paul McGee and Bar DeVille’s Brad Bolt, introduced it to new audiences with cocktails that incorporated the liquor but smoothed out its rough edges with other ingredients.