Plenty of people start life coloring outside the lines. But sooner or later, the pressures of convention reel them in. It takes an unwavering self-assurance — or blind madness — to stick to one’s vision. Edgar Miller was neither a renegade nor an iconoclast, but this multitalented creative refused to be sidetracked by the expectations of others.

A jack-of-all-trades and master of many, he was an accomplished architect, painter, graphic designer, and muralist. He sculpted in stone and plaster, carved wood, and worked in stained glass. Miller, who died in 1993, has never been forgotten in Chicago, but as with anyone who never fit neatly in a box, it doesn’t hurt to shine a light his way from time to time, as the DePaul Art Museum is with the exhibition Edgar Miller: Anti-Modern, 1917–1967, on view September 12 to February 23.

“Once you know about Miller and where to look, you realize that his hand remains visible all around Chicago.”

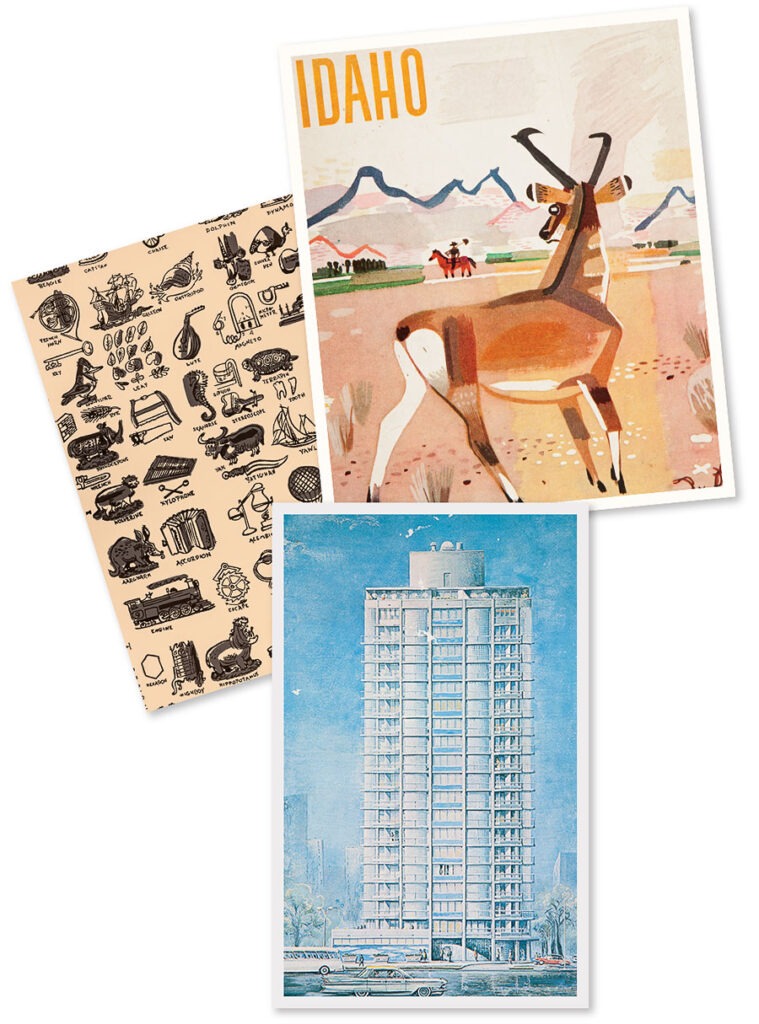

Born in Idaho in 1899, Miller arrived in Chicago to attend the School of the Art Institute. Though he dropped out, he stayed in town for most of his professional life. Deploying an aesthetic that embraced a range of styles, from neo-Gothic to art deco, he operated in a kind of William Morris mode, celebrating craftsmanship and reveling in the ability to fashion nearly every aspect of a built environment.

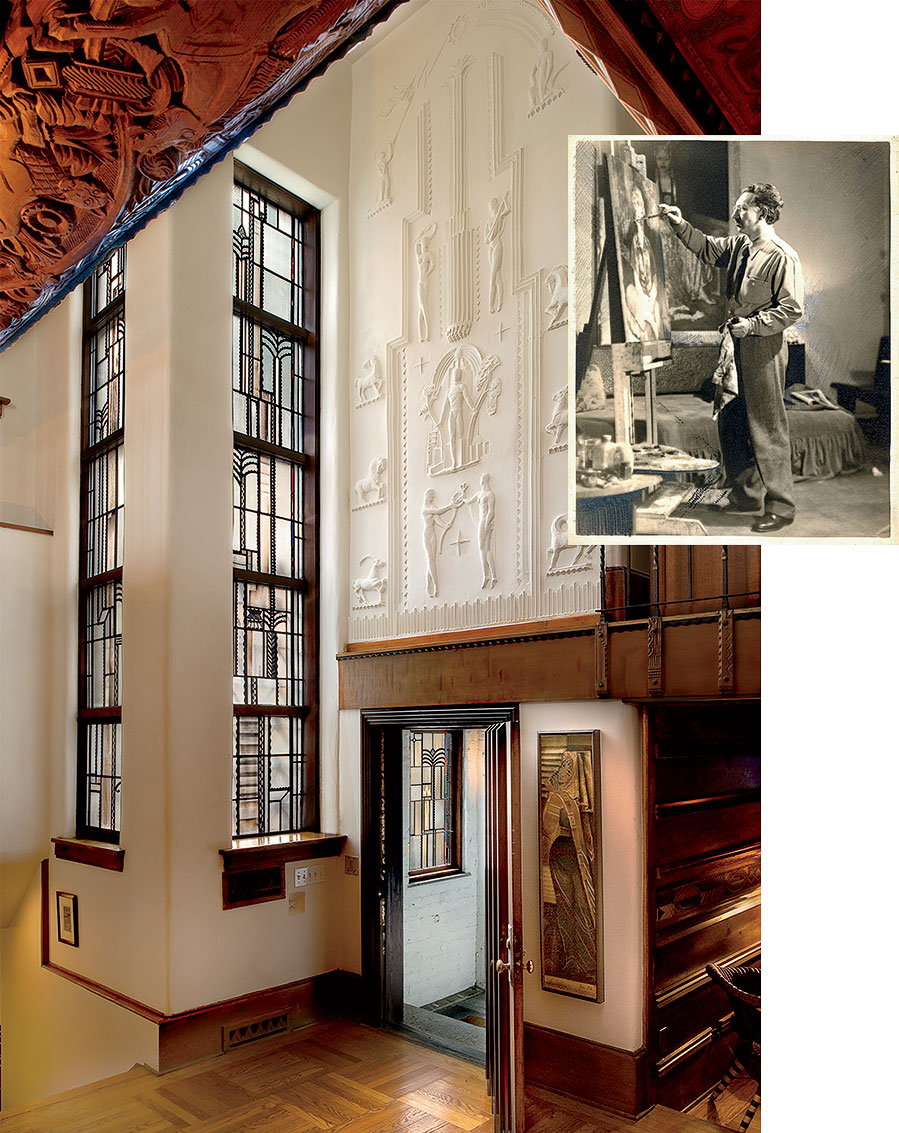

Arguably the most notable of these are the live-work spaces he created in Old Town: the Carl Street Studios, at 155 West Burton Place, and the Kogen-Miller Studios at 1734 North Wells Street. Miller was a great recycler, and salvaged steel, glass, wood, and stone found their way into these near-maximalist compositions. Compared with the clean-cut philosophy of modernism in the 1920s and ’30s, Miller’s style was downright bohemian.

A 1932 Architecture magazine profile described him as a “modest” artist who “labors hard and incessantly with an inner satisfaction.” But Miller was no Henry Darger of the design world. He was a regular at both the Dill Pickle Club, a progressive spot that hosted the likes of Margaret Sanger and Clarence Darrow, and the Tavern Club, which counted William Wrigley Jr. among its members. He did commercial work for Marshall Field & Company and the Container Corporation of America and designed wallpapers for Bassett & Vollum, several of which are still available today. The DePaul exhibition features a range of Miller’s work — sketches and drawings, advertising graphics, tableware, stained glass, and furniture, including a carved wooden bench from the Normandy House, a restaurant on the Magnificent Mile.

“Once you know about Miller and where to look, you realize that his hand remains visible all around Chicago and the Chicagoland area,” says the exhibition’s curator, Marin R. Sullivan. “Some of these projects are now destroyed or have been relocated to museum or private collections, but a large number are still in situ and in public or semipublic spaces.” Publicly accessible favorites include bas-reliefs Miller did for Northwestern’s Technological Institute, his various contributions to the Madonna della Strada Chapel at Loyola, and the cut-lead panels for the entryway of what’s now Century Tower.

After moving to Florida in the late 1960s and then, following his wife’s death, to San Francisco, where his children lived, he returned to Chicago in 1986 and remained here until his death at the age of 93. “He never stopped working,” says Sullivan. “While not undertaking many high-profile commissions upon his return, he continued to work on the Kogen-Miller and Carl Street Studios complexes, making new architectural elements, including stained glass windows.”

Though widely feted during his time, Miller never established a school or wrote much about his work. But as he told the Chicago Tribune’s Alan Artner in 1978, “My great desire was to communicate with others in a common language. The human being who relates to human beings is the one who achieves something.”