As long as I can remember, Chicago has been besotted by the size of its monuments. Biggest. Tallest. Busiest. This makes the Morrison Hotel — the tallest iteration of which, if it still stood, would have turned 100 next year — twice blessed. At one point, it was the tallest hotel in the world. At another, it was the tallest building ever torn down in America.

As always in Chicago, it starts with real estate. This is less the story of a tower than a marsh, a parcel of riverfront acreage that became a bustling street corner. In it, you have the history of the city condensed to concentrate. In the 1770s, when Chicago’s first and only resident, the free Black trader Jean Baptiste Point DuSable, was living in the house he built on the lake at what is now the Magnificent Mile, the future site of the Morrison was an undistinguished piece of the woodland near the spot where the river originally met the lake. The ground was dead leaves, fallen branches, wild raspberries. In the spring, when the ice melted and the sound of water was like blood returning to the veins, the gullies bloomed with the wild onion that gave the city its name. “Chicago” derives from the Algonquin word “shikaakwa,” which means something like “the place with all the ramps,” or “the place with the smell.”

The Morrison lot had probably been cleared by 1803 — the intersection of river and lake had been a trading post for Native Americans and French trappers — when the federal government built Fort Dearborn nearby, establishing an outpost in a wilderness that ran nearly unbroken to the Pacific. Potawatomi warriors burned down the fort on August 15, 1812. On the same day, a hundred years later, the Cubs beat the Braves 10—7. Fort Dearborn was rebuilt, then destroyed again, this time by savages: the real estate men and city fathers who mapped Chicago’s first streets.

By 1840, the Morrison lot had been turned into a crossroads: Madison and Clark. In the early 1900s, when Chicago was experiencing its second boom, Madison, considered one of the world’s busiest streets, was crowded with trolley cars, carriages, men in suits and fedoras, and women who dressed as if every day were Sunday. The meeting of these great urban arteries might as well have been the navel of the world.

The city’s first police chief and first coroner — Orsemus Morrison, a name as antique as a kerosene streetlamp — purchased the lot on the southeast corner of Clark and Madison in 1838, before the city had 5,000 inhabitants. He held the land for 20 years, then, with the population nearing 100,000, he began to build. The earliest iteration of the Morrison Hotel was a three-story structure with 21 rooms. It looked like something out of the Old West, a raw dive in a frontier town. The saloon was spittoons, fistfights, and men playing faro.

On October 7, 1871, the lobby was filled with speculators, politicos, gamblers. Potter Palmer was running his big new joint on State Street. The team that would become the Cubs — they played in the Union Base-Ball Grounds at Randolph and Michigan, current site of Millennium Park — was in the last weeks of their second season, which ended with them in second place, two games behind the Philadelphia Athletics.

On October 9, 1871 — that is, two days later — the Morrison was gone, destroyed in the great fire that reduced some four miles of that ur-downtown to ash, burning everything from the gloves and bats of the baseball team to the hotels, dry goods stores, feed shops, oyster houses, and saloons that had characterized the city. That first Chicago, which was as different from the modern city as the past is from the present, lingers in the collective subconscious. It’s the foundation on which the metropolis is built. In its center, glowing like a dream of raw youth, is the Morrison Hotel.

It was the Hancock of its time, the Sears Tower. It was the exclamation point that punctuated everything. Then it wasn’t.

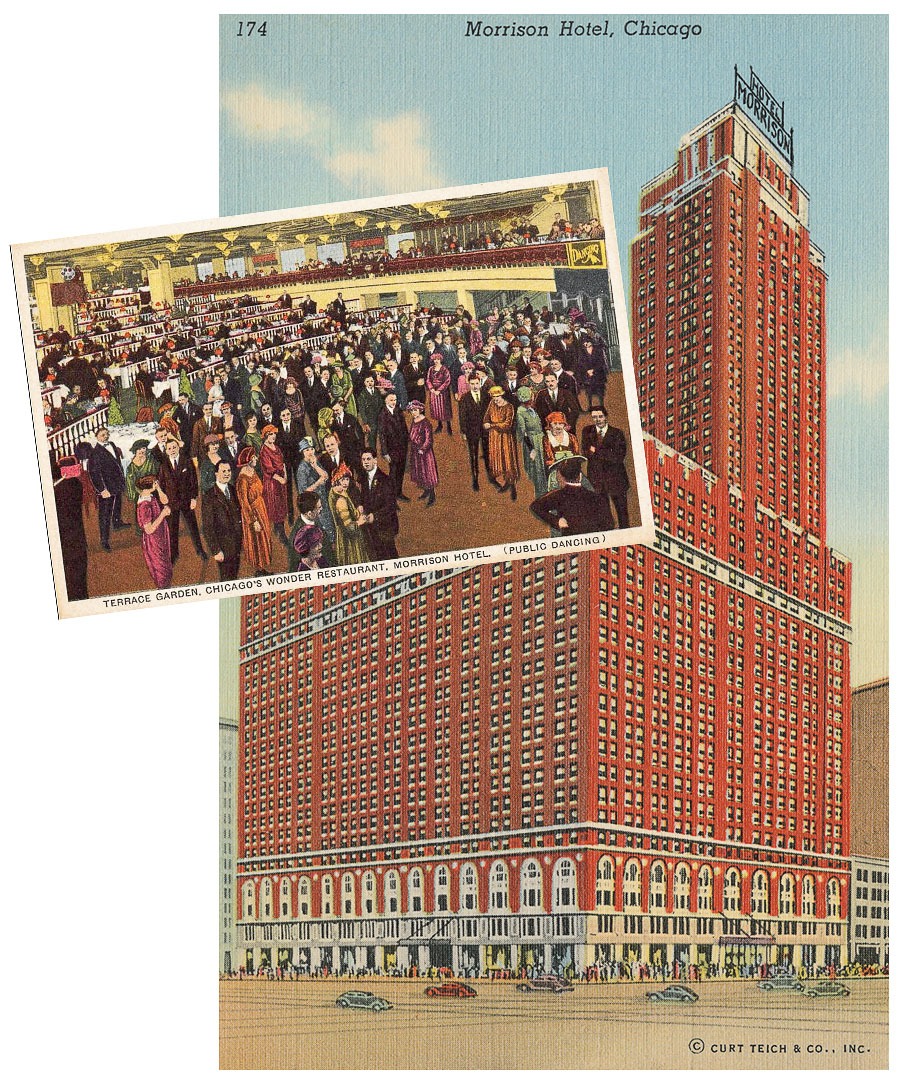

Orsemus Morrison rebuilt the hotel, then deeded it to his nephew, who sold it to an Indian-born businessman named Harry Moir, who, as was the spirit of the age, renovated, renovated, and renovated again. By 1918, the Morrison was 21 stories of luxury: 650 rooms, each with a valet-summoning bell, an en suite bath, and views of the city, the lake out this window, the slaughter yards out that. Smoke rose above the U.S. Steel yard in Gary, the stacks belching out flame. The trains arrived all through the night.

Moir added the hotel’s 46-story tower in 1925. With more than 2,000 rooms by 1935, the Morrison had become a nexus of Chicago’s social and psychic life, one of the first things travelers saw as they approached from the east, a brick tower rising like Vesuvius from the bottom of the sea. It’s where the great University of Illinois running back Red Grange, the Galloping Ghost, hid from reporters before signing football’s first megacontract with the Bears in the lobby. The newspaper photo of Grange, the Wheaton Iceman — he had the hands of an artist and the face of a miner — grinning beside the young, flinty, lantern-jawed George Halas is Chicago in a phosphorescent flash.

The Morrison was one of those hotels you never had to leave, where you could shop and dine, get drunk and be entertained, without ever stepping outside. It was like Opryland in Nashville or the Bellagio in Vegas. Its life was a premonition of the postapocalypse, when, as in the movie Logan’s Run — seen by me at the Edens Theater in Northbrook in the summer of ’76 — war, environmental catastrophe, or alien invasion would drive us beneath a dome.

The Morrison’s Terrace Casino opened in 1936, with Sophie Tucker singing “How Ya Gonna Keep ’Em Down on the Farm?” Louis Armstrong performed there, too, as did Benny Goodman, Duke Ellington, Count Basie, and Nat King Cole. Then there was the Carousel in the Sky, which billed itself “the tallest nightclub in the world.” Wrestler Gorgeous George had his hair styled and nails polished in the Morrison’s beauty salon nearly every day. Eisenhower, Truman, John F. Kennedy — they all stayed at the Morrison while begging Middle American votes. Vice President Nixon sat brooding in a room upstairs, drinking Scotch and pitying himself in third person.

The Morrison, which, at some point, changed its name to the Chicagoan, was the Hancock of its time, the Sears Tower. It was the exclamation point that punctuated everything. Then it wasn’t. The rooms, which had been the most modern, the ballrooms, which had been the biggest, the nightclub, which had been the highest, were suddenly passé, superannuated. As the 1940s turned into the 1950s, then into the 1960s — it never goes the other way — the hotel, which had been a gem, vanished beneath a forest of even taller towers, just as the ground of the lot had once been overshadowed by oak trees. Rooms that had been state of the art suddenly seemed frowzy. By 1963, when my mother stayed at the Morrison on her first visit to Chicago — its lobby was her personal Ellis Island, the gateway to a new life — it had become a disappointment. (“What can I tell you, Richard. The place was a dump.”) The Carousel, which had been the haunt of top-tier gangsters, the Nittis and Capones, had dilapidated to the bookie and number-runner level, Bellowian characters chewing toothpicks in the shadows of the once grand lobby.

It had been the headquarters of the Democratic machine since the 1930s. The original Mayor Daley remained a presence in 1965, making deals and pulling strings, when the new owners announced their decision to raze the joint and replace it with the 60-story black monolith that still occupies the site. It was a bank office and remains a bank office: the Chase Tower. I never pass the southeast corner of Clark and Madison without picturing the Morrison Hotel, the antediluvian inn and the skyline-defining tower it became, a steeple rising above the city to point the way up. Because of what it meant. Because of what it survived. Because of what had happened there. Because of Red Grange and Sophie Tucker and Capone’s torpedo leaning close enough for you to see the pistol beneath the houndstooth blazer. Because of Gorgeous George, eyes closed for his manicure. Because of Ike smiling as he walks through the front doors. Because of red-faced Mayor Daley cannonballing down the carpeted hallway as he shouts to a flunky: “Get that sonofabitch judge on the phone.”

When the Morrison first went up, Chicago was a city with no past and no history. It was nothing but tomorrow and the day after that. When the hotel came down, the city’s past was so rich that it threatened to overwhelm the present.