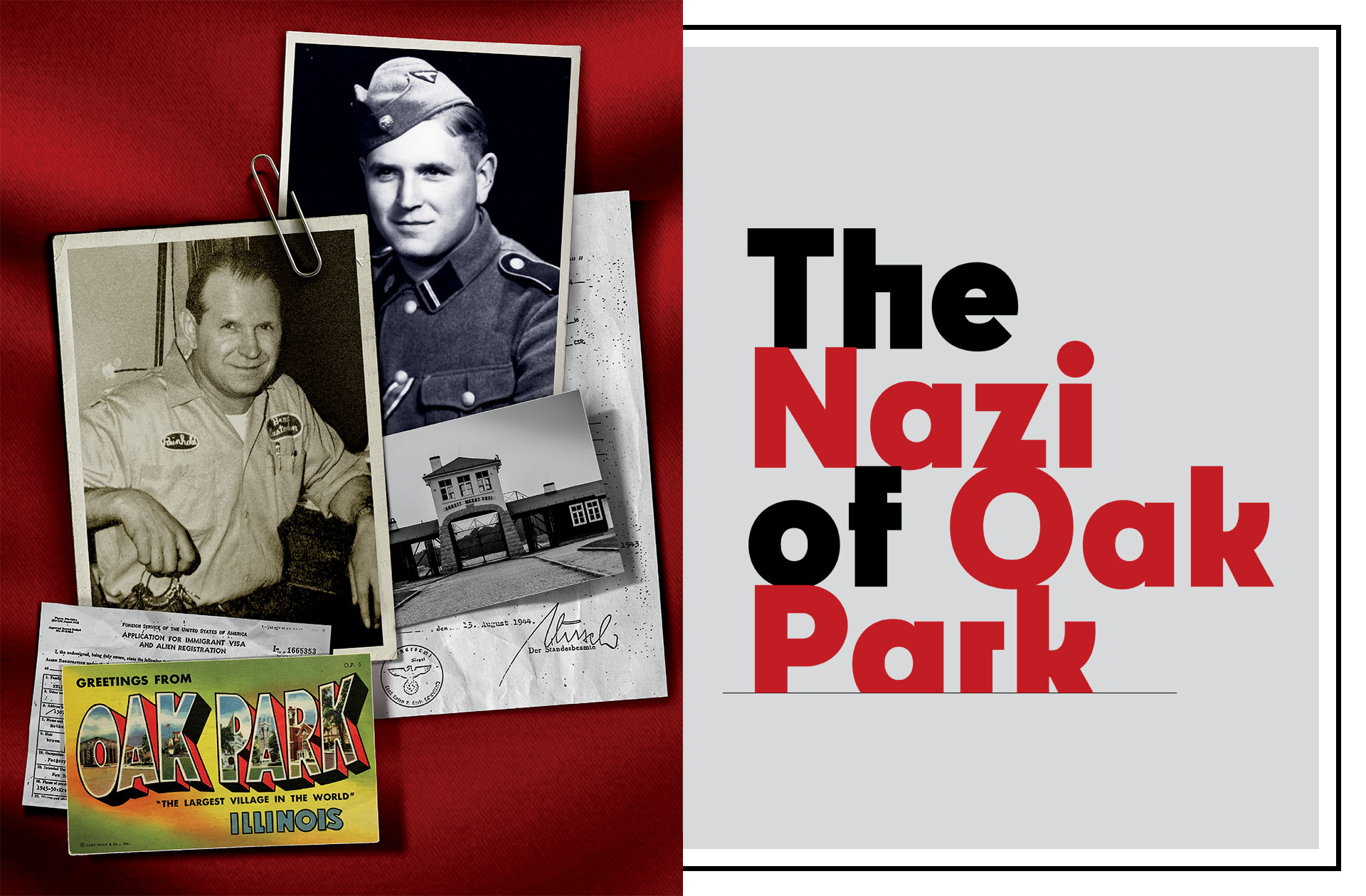

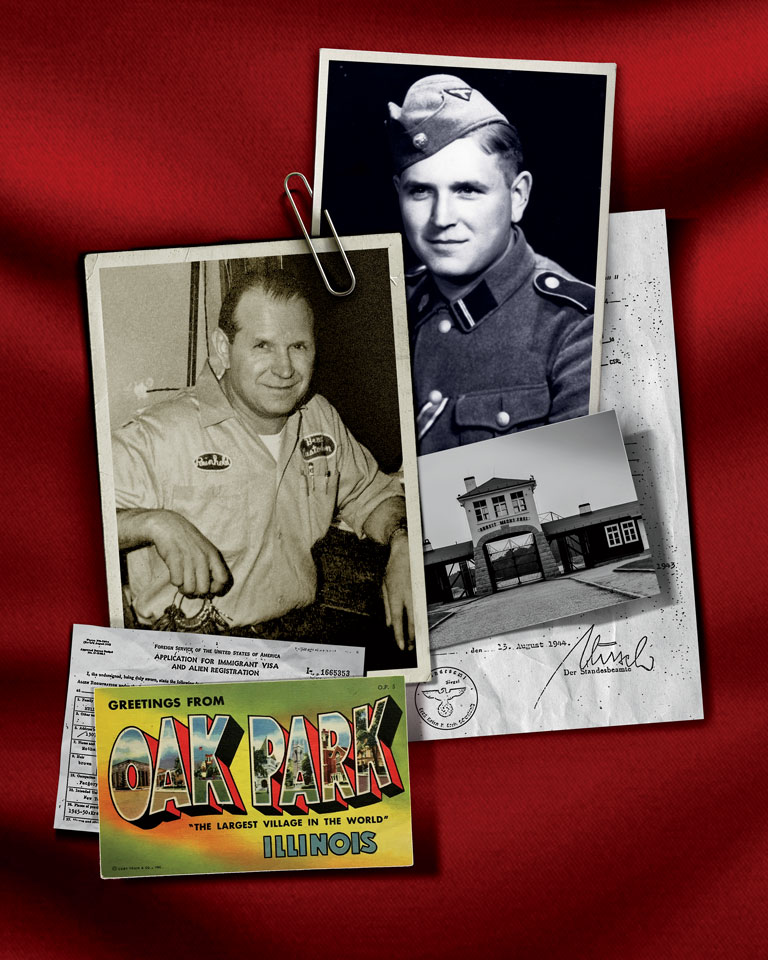

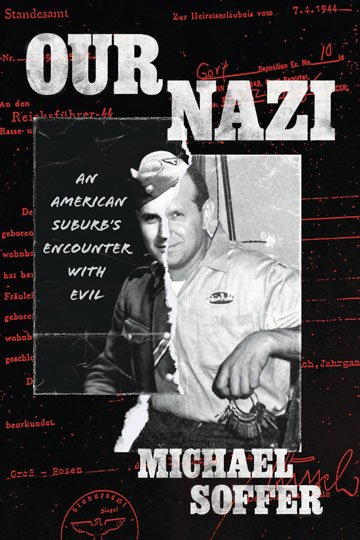

Adapted from Our Nazi: An American Suburb’s Encounter With Evil by Michael Soffer, with permission from the University of Chicago Press. © 2024 by the University of Chicago. All rights reserved.

Jack Swanson walked into his second-floor office at Oak Park and River Forest High School. It was December 4, 1982, and this three-room suite next to the boardroom had been his for the last eight years, after he had beaten out 60 other administrators vying to run the storied west suburban school. The normally bustling building was quiet, the 3,400 students enjoying the unseasonably warm Saturday at home.

Swanson exuded calm and professionalism. Deeply religious, he was in some ways a throwback to Oak Park’s more genteel past, when the village was informally known as Saints’ Rest. When he first took the reins at the school, Swanson had streamlined its administrative structure, and had told the local papers that he wanted to ensure that Oak Park was a “viable community” for people from diverse backgrounds.

Oak Parkers had always felt there was something special about their town. It had raised Ernest Hemingway and was home to a dozen of Frank Lloyd Wright’s iconic Prairie-style structures. Oak Parkers’ pride was reflected even in the high school’s motto: “Those Things That Are Best.” The village no longer resembled the conservative community that Hemingway once quipped had “wide lawns and narrow minds.” Oak Park had become a national model for integration, recognized by the National Civic League as an All-America City at the end of Swanson’s first year.

Trim and dignified, the 54-year-old superintendent readied for a quiet morning of paperwork. Outside his window, large Victorian homes sat across sleepy Scoville Avenue. Swanson settled into his chair and opened the Chicago Sun-Times.

A headline on the bottom right-hand corner of page 7 caught his eye: “Deportation Bid on Suburb Man.”

He scanned the article, and a wave of shock rushed over him. It had to be a misprint, some kind of misunderstanding. Maybe it was a different man with the same name? No, the Sun-Times left no room for doubt.

Swanson fumbled for his phone and dialed school board president Paul Gignilliat, unsure of what exactly he would say.

Gignilliat was relaxing at his home two blocks away when his phone pierced the morning quiet.

“Have you noticed?” Swanson bellowed. The next few seconds were a blur, the words almost impossible to believe. But Swanson wanted Gignilliat to hear the news from him directly: Reinhold Kulle, the high school’s chief custodian, had been a Nazi.

It was 1957, and the U.S. Consulate in Frankfurt, Germany, was abuzz with activity. Katherine Geoghegan, one of the consulate’s veteran officers, ushered a new visa applicant and his family into her office. A physician had just examined them, drawing their blood and listening to their hearts.

This interview was the final step in the monthslong process. It was exciting and nerve-racking for the applicants, but routine by now for Geoghegan. She placed the applicants under oath and offered them a seat.

Geoghegan looked at the soon-to-be-American family in front of her. Reinhold and Gertrud Kulle made a handsome couple. He had kind eyes and a warm smile and answered her questions patiently. Their daughter, Ulricke, was 12; their 8-year-old son, Rainer, was the spitting image of his father.

Kulle had first contacted the consulate a few months earlier. It had sent him a detailed preliminary questionnaire to fill out, along with an information sheet, translated into German, that explained the application process and listed the classes of individuals who were ineligible for American visas.

Geoghegan looked over the paperwork and asked the family a series of questions through an interpreter.

Kulle had served in the German army, which was not surprising; nearly every German man had been conscripted by the end of the war. But on the preliminary questionnaire, he indicated that he had not been in any organizations that would have barred him from entry, and no derogatory information had come back from the consulate’s background check. He had a job waiting for him with a rivet company in Chicago, and a place to stay, with one of his wife’s relatives.

It was hard to imagine a better candidate. Geoghegan had just a few last questions that her bosses stressed she and other officials ask each candidate.

“Are you a member of the Communist Party?”

“Were you a member of the Nazi Party?”

“Were you a member of the Waffen-SS?”

Reinhold Kulle’s warm smile covered the dark secret he had closely guarded for over a decade. He had kept it in Krempe, the northern German town where the Kulles had fled after the war, and in Lahr, where they had moved after Rainer’s birth, and on the forms Reinhold had sent to the U.S. Consulate.

If Geoghegan somehow found out that he had been in the SS, a member of its elite Totenkopf (Death’s Head) division, and had served as a guard at Gross-Rosen, a forced-labor concentration camp in Silesia, now part of Poland, everything would be over.

But she didn’t.

Geoghegan signed visa application No. 6037. Reinhold Kulle was officially welcome in America.

With its patchwork of ethnic neighborhoods, Chicago became one of the most common landing spots for former Nazis in the years after the war. Liudas Kairys, a guard at the Treblinka killing center in occupied Poland, was among the throngs of Lithuanian immigrants who settled on the Southwest Side. He arrived in 1949, claiming to be a displaced person, and took a job packaging candied popcorn at the Cracker Jack plant near Midway Airport. A few miles south, Hans Lipschis was often up early to work on his house. A Lithuanian member of the SS at Auschwitz, Lipschis came to Chicago in 1956 and found work at a factory making guitars. A year later, Conrad Schellong, a former concentration camp guard, moved to Lake View with his wife and three kids, living in several apartments within a few blocks of Wrigley Field. He worked as a welder and as a janitor for the Chicago Tribune. There were others, too — Michael Schmidt in suburban Lincolnwood, Joseph Grabauskas on the Southwest Side, Bronislaw Hajda in Schiller Park, and Juozas Naujalis in Cicero — so many that investigators would later joke that America’s Nazi-hunting organizations could have moved to Chicago and ignored the rest of the country.

Chicago became one of the most common landing spots for former Nazis after the war. Investigators would later joke that Nazi-hunting organizations could have just moved to Chicago.

The Kulles first stayed in suburban Forest Park, with Gertrud’s relative. Much of the land that became Forest Park had been purchased shortly before the Civil War by Ferdinand Haase, a German immigrant, and the village’s first major businesses were the German Waldheim Cemetery, the Deutsche Altenheim (German Old People’s Home), and Karl Lau’s sausage factory. Though it was becoming more ethnically diverse when the Kulles arrived, Forest Park still retained a large German cohort.

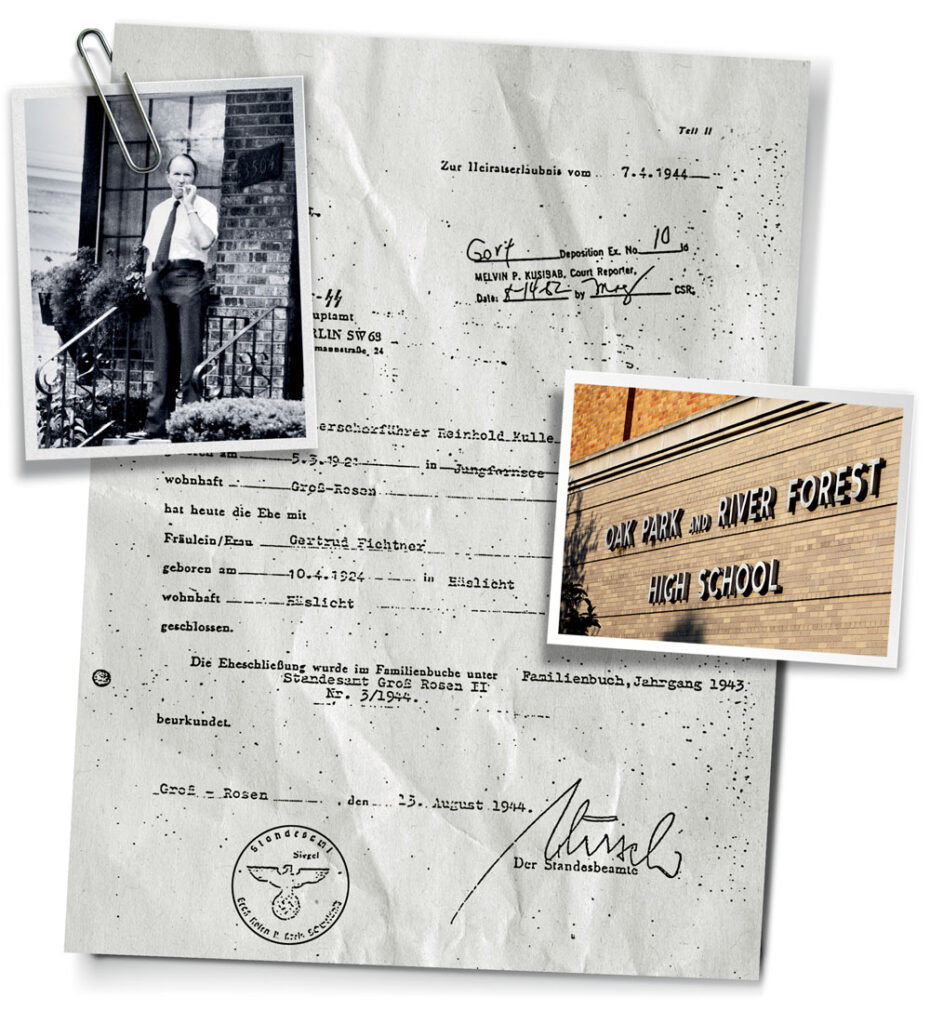

In 1959 there was an opening on the custodial staff at Oak Park and River Forest High School, and Kulle applied. He was quickly hired. Before he could officially start, he had to fill out paperwork. He did so in English, though he was still learning the language. In block letters, all capitalized, he wrote that he enjoyed gardening. During his physical, the medical examiner noted an “operational scar” on Kulle’s abdomen and “two wound scars” on his skin. Among the other papers in his personnel file was his marriage certificate, listing him as “SS-Unterscharführer Reinhold Kulle” and the registry office as “Groß-Rosen II.” Stamped on the bottom of the page, the Reichsadler eagle looked off into the distance, a swastika below its perch. If anyone at the high school was concerned, they kept it to themselves.

Kulle soon proved hard-working and indispensable. OPRF’s leadership took notice, and when the head night custodian fell ill in 1963, administrators asked Kulle to fill in. His English was still a work in progress, but he handled the added responsibilities well. When the ailing head custodian retired a few months later, Kulle was officially appointed his replacement.

Kulle’s steady work meant that his family could afford to move into a house of their own. Their first was a few blocks north of the Eisenhower Expressway on Harlem Avenue, the line separating Forest Park from Oak Park. It was just around the corner from Otto’s Restaurant, to which the Kulles could walk for schnitzel, Thuringer, calf’s liver, sauerbraten, and herring, and the kids could enjoy strudel or German chocolate cake for dessert.

Like Kairys, Lipschis, and Schellong, Kulle lived simply and quietly. He paid his bills, doted on Ulricke, and cheered for Rainer at wrestling matches. He avoided politics and stayed out of trouble. In his spare time, he gardened. He slipped into obscurity, just another blue-collar worker in Middle America with a thick accent and an untold past.

After a dozen years at OPRF, Kulle had become every faculty member’s go-to. He knew where everything was, an impressive feat in a four-story behemoth of a building occupying an entire city block. Science teachers could count on him to escort students down to the school’s drafty basement to grab beakers, acids, and other materials for experiments. One day, he saw a colleague frantically setting up a college fair. When the man anxiously explained that he was running behind, Kulle immediately reassigned his crew to take over the setup.

His staff was among the best in the building, and the school was renowned for its cleanliness. Kulle rarely missed a day of work. He worked through injuries, like the time his hand had slipped through a glass window when he was cleaning it, or the time a few months later when he had stepped on a wooden board and nails had punctured his shoe, lacerating his foot.

Even as a supervisor, overseeing 30 custodians, Kulle continued washing hallway floors with the power scrubber and cleaning the library carpet on his hands and knees. A staff member once complained that Kulle’s hard work diminished opportunities for overtime, but Kulle took pride in keeping the building immaculate, and the faculty, administration, and staff respected him for it.

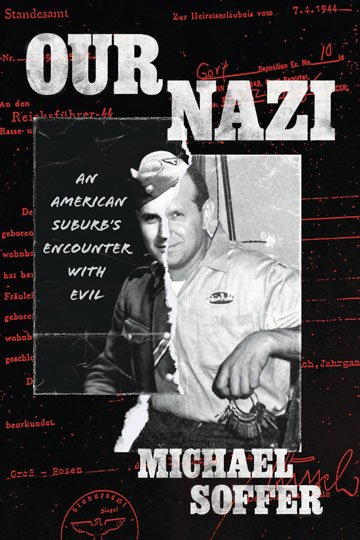

“At night,” a local newspaper explained, “he’s boss at [the] high school.” Tucked in the back pages of the Oak Leaves, the simple profile of the OPRF janitor described him warmly as a “refugee from East Germany” who kept the floors clean, the kids in line, and the school running on time. “There’s something in Reinhold Kulle’s voice that tells you he means it,” it began. The article was accompanied by a posed picture of Kulle: shoulders slightly hunched, a faint smile, and a short-sleeved work shirt tucked into his dark pants. His name was stitched in cursive above the pen in one breast pocket, and he had a small notebook in his other. Though he had gained a few pounds, he was still fit: his shoulders broad, his body solid. The huge ring of keys he typically carried for access to every room in the building was just out of sight.

At high school dances, explained Kulle in the article, he walked around to make sure students were not drinking. It was important to set a strict tone at the outset: “When you stop it the first night, then that’s all you have to do.” Although Kulle was often in contact with students, he did not get to know them well. He had learned somewhere in his past “not to get too close to [them] because those relationships might interfere with his enforcement of the school’s rules.” The high school was Kulle’s domain. “Whether it’s an evening class or a little theater event, Kulle is usually there, standing guard,” the paper noted.

Kulle had become something of an institution at OPRF. He adored the school, and the feeling was mutual. OPRF compensated him well — he earned more than many of the teachers. As his English improved, Kulle formed strong friendships with his colleagues, inviting them out to Oktoberfest celebrations and giving recommendations and reviews of Chicago’s German restaurants. Students in OPRF teacher Herr Schoepko’s German classes occasionally tried to practice with Kulle in the hallways. He would engage politely and briefly before returning to his work. A more awkward encounter came when the theater department asked whether the set for their production of The Sound of Music looked authentic. He shrugged; it was not worth explaining that he was a German citizen from a town that was now in Poland while the play’s story took place in Austria.

It wasn’t just any letter. It was from the Department of Justice, which had questions about the war and wanted to talk.

The summer usually brought calm. Just weeks earlier, the senior class had bidden OPRF a final farewell. Kulle was one year closer to retirement — to being at home with Gertrud in Brookfield, where they had moved after their children had left the house and married, to spending his days in the garden, to having more time with the grandkids. After the graduation ceremony, the custodial staff broke down the chairs and cleaned up from the event. Soon the building would be quiet again.

But at the end of July 1982, the Kulles received formal correspondence from the deputy director of the Justice Department’s Office of Special Investigations, created to track down Nazis and their collaborators now living in the United States. OSI had scheduled a meeting with Kulle, and because he was not a U.S. citizen, he had no choice but to go. Gertrud told OSI attorney Bruce Einhorn that Reinhold would take OSI up on its offer to provide an interpreter.

On Saturday morning, August 14, Einhorn waited for Kulle at the Midland Hotel in downtown Chicago. He placed an American flag on OSI’s side of the table. Kulle might not have noticed, but the symbolism was important to the 29-year-old curly-haired prosecutor. Einhorn, a Jewish kid from Brooklyn and the descendant of a prominent American rabbi, would be standing over a Nazi.

Einhorn had a file of documents gathered over the past year from the Berlin Document Center and the Immigration and Naturalization Service. They were more than OSI could have hoped for. The documents included not only Kulle’s SS personnel file but the marriage application Kulle had filed with the Reich Security Main Office. They had Kulle, in his own handwriting, detailing his Nazi history, proudly recalling his time in the Hitler Youth and Waffen-SS, and assuring Reichsführer Heinrich Himmler that there were no Jews in Kulle’s bloodline. They even had photos of him in his SS uniform.

When Kulle arrived, Einhorn was almost relieved by his appearance. Now 61, Kulle still had a powerful frame, though his hair was thinning on top. Most important, he looked exactly like he did in the photos OSI had of him in uniform. Kulle had come without an attorney, and the interview began just before 11 a.m.

Einhorn walked through Kulle’s childhood in Silesia. “Have you always gone by that name?” “Where and when were you born?” “What was your father’s name?” More questions, straight from Kulle’s SS files, followed. “Have you ever had the measles?” “Did you ever have scarlet fever?” “You are approximately 170 centimeters tall?” The questions seemed innocuous enough. They were confirming, though, that the Reinhold Kulle of Gross-Rosen, Silesia, was the Reinhold Kulle of Brookfield, Illinois.

Kulle freely acknowledged having volunteered for the SS and joining the Death’s Head division. He described his service in occupied France and the wounds he had suffered on the eastern front. He answered before the questions could be translated into German. Einhorn repeatedly reminded him to wait for the translation, but it was clear that Kulle’s English was now quite fluent.

Einhorn asked whether he had received any decorations for his service. Yes, Kulle said, but they had been lost when the family fled Silesia. He did have a picture to show Einhorn: one of him in his uniform, with the Death’s Head insignia, and with patches and stripes that denoted the medals he had received. The photograph was one of the only items Kulle still had from the war, a remnant he had managed to keep and protect for nearly 40 years. Einhorn looked at the photo and then up at Kulle.

“I take it this photograph means a great deal to you,” he said.

Kulle dismissed the remark. “It doesn’t mean anything today.”

Though he freely acknowledged his military service, Kulle was coy about anything connected to Nazi persecution. He tried to portray his time at Gross-Rosen as strictly military duty, saying he had nothing to do with the prisoners and was only at the camp to train recruits. He clearly understood that admitting to more could spell trouble, but once he had acknowledged that he was the same Reinhold Kulle who had been born on March 5, 1921, in Breslau, in the then-German province of Silesia, his protestations were of little value.

Once back in Washington, D.C., Einhorn and his colleagues prepared to begin formal deportation proceedings.

For two days that December of 1982, OPRF superintendent Jack Swanson walked through the Oak Park community, almost singularly carrying a bombshell. So far, the school had been spared any publicity. The Sun-Times article had not mentioned OPRF, and the Chicago Tribune had misidentified Kulle as a custodian at an elementary school in Brookfield.

But it was only a matter of time. Eric Linden, the lead reporter for Oak Park’s Wednesday Journal, had already asked for a comment. Swanson exuded his typical patience and calm, responding that Kulle was “an exemplary employee who will continue to work here at least until some kind of a court decision is made.” It was premature to do anything else, he explained. Everyone just needed to let the legal process play out.

That Monday afternoon, Swanson asked Kulle to come to his office before his shift began. Everyone knew that Kulle had been in the German army. He used to joke with the American veterans on his staff about the possibility they had shot at each other back in Europe. But a concentration camp guard? Reinhold? There was no way.

Swanson could not change the past, but he certainly wished the revelations had not been unearthed. He could never know exactly what had happened a lifetime ago and a world away. But he knew Reinhold, the kind of man he was now. They had become friends. He dreaded having to ask him about the allegations. His focus needed to be on the future, on students, on the budget. It was his job to do what was best for the school, and Kulle was an irreplaceable asset.

Kulle walked in, his collared short-sleeved work shirt covering the slight paunch of middle age. Swanson looked him in the eye and asked if the allegations were true. Had he really been a guard at a Nazi concentration camp?

Yes, Kulle told Swanson, he had worked at Gross-Rosen, but he had never even fired his rifle. It was just a prison, he added.

And he hadn’t said this on his visa application?

No, Kulle admitted. He had not.

And he had been in the Hitler Youth?

Yes, Kulle answered. He had joined the Nazi youth movement as a teenager, but he had never been an active participant.

Swanson peered through the large, thin-framed glasses that crossed his angular face. Kulle looked uneasy, as if he knew he was in trouble. Swanson was not finding his answers convincing. But after 23 years, Kulle had earned some compassion, some grace.

Swanson had to determine how to navigate OPRF through the ordeal to come. He hoped it would all just go away. Kulle had been a young man in the war, doing what everybody else at the time was doing there. And so many years had passed. The man at Gross-Rosen, Swanson told himself, had been a different Reinhold Kulle.

Early one August morning in 1983, RaeLynne Toperoff was reading the Chicago Tribune at home in Oak Park, enjoying a day off from the summer program she was teaching. The veteran Chicago Public Schools educator flipped through a dozen pages full of advertisements for back-to-school sales.

Then, above a large ad for a new Apple computer, the word “Nazi” caught her eye. Another of Hitler’s men had been caught. Good, she thought, scanning the short article about a deportation hearing.

Then she saw it.

“The Oak Park school maintenance man…” She read the line over and over, thinking her eyes were playing tricks on her. How had she not heard about this before? She thought about her school-age kids. At which school was this Reinhold Kulle working?

Toperoff grabbed her phone and called Rima Lunin Schultz, a close friend from her synagogue. Toperoff began to explain what she had read but soon gave up and instead scurried the four blocks to Lunin Schultz’s house to tell her in person.

There was one question that RaeLynne Toperoff could not get out of her head: Why, if it was already determined that Reinhold Kulle was a known member of the SS, was he still employed at the high school?

They tried to figure out where the hearing was being held. Something they could not yet articulate was compelling them to go, to witness the proceedings. From Lunin Schultz’s kitchen, they called local leaders, Jewish organizations, anyone they could think of. “Where is this happening?” they kept asking, but nobody seemed willing or able to tell them. Exasperated, Lunin Schultz called the Justice Department itself.

“I’d like to speak to whomever is involved with the matter of Reinhold Kulle,” she said. She was put through to Einhorn’s hotel room, and the attorney told her how to get to the courtroom at the Dirksen Federal Building in downtown Chicago.

Toperoff and Lunin Schultz raced the two blocks south to the L stop and boarded the Green Line train. By the time they entered the courtroom 45 minutes later, the hearing was well underway. Toperoff looked over to the defense table. There he was, this Nazi, this Kulle, sitting in an American courtroom, getting due process and a prominent lawyer.

On the other side of the courtroom, by the OSI table, several elderly women sat together. Lunin Schultz and Toperoff knew instantly that they were survivors. Without saying a word, they walked over to sit with the women. They looked around the courtroom to see whether anyone else they knew from Oak Park had come. Sure enough, a contingent sat on Kulle’s side of the room, near a cadre of neo-Nazis. Toperoff and Lunin Schultz stared in disbelief. Their neighbors had walked into the same contrast they had seen — Holocaust survivors on one side, a former Nazi on the other — and had chosen their seats differently.

At the end of the long and emotionally exhausting day of testimony, there was one question that Toperoff could not get out of her head: Why, if it was already determined that Kulle was a known member of the SS, was he still employed at the high school?

As the first phase of the hearing came to a close, 20 members of the high school’s maintenance staff wrote a public letter chastising the Oak Leaves for reporting on the proceedings in a “sensational manner” and for not including “even one item in support of Mr. Kulle.” Had the paper sent reporters to OPRF, Kulle’s colleagues wrote, it would have learned that Kulle was “held in high esteem at the high school” and that the “school and community are just a little better because Mr. Kulle has been here.”

RaeLynne Toperoff put down the paper in a fit of disgust. “The same cannot be said of his Gross-Rosen victims,” she thought. The next week, as if in response to the custodial staff’s letter to the Oak Leaves, the Wednesday Journal sent Eric Linden to the high school. Kulle’s boss, the assistant director of buildings and grounds, told the reporter that Kulle remained “respected” and “popular” and that the charges had “not changed that impression.”

Rima Lunin Schultz was following OSI’s other cases, and she knew that those situations were difficult. There was little precedent for how a community or an employer should handle such allegations. But Oak Park was supposed to be different. It was, she explained to anyone who would listen, “better equipped to deal with these kinds of issues than other communities.”

Each Wednesday, Lunin Schultz opened the weekly papers with trepidation, anxiety, and a pair of scissors, collecting each article and letter about Kulle and placing them in a box. She and Toperoff bristled at Linden’s gentle portrayals of Kulle and at the absence of historical context about the slave labor at Gross-Rosen. They were relieved to see, in the middle of September, that they were not entirely alone. Three men sent a letter to the Wednesday Journal expressing outrage at the “good guy image” in Linden’s recent piece.

Still, the women knew they were in the minority. Linden said as much when Toperoff called him. Kulle’s colleagues still supported him, the school continued to employ him, and even the local press was sympathetic. Kulle seemed to have the support of Oak Park’s most powerful institutions.

Searching for allies, Lunin Schultz, Toperoff, and their husbands attended a meeting of a small new group organized by Bruce and Julie Samuels, who were active in progressive politics and environmental issues in town. Bruce Samuels thought the Kulle situation was a symptom of an ignorance of history, especially Holocaust history, and he hoped to push the high school to improve its curriculum. His goals were expressed in the lofty name of the group: Coalition for an Informed and Responsible Citizenry.

That October, the school board received an anonymous letter, seemingly from faculty members, requesting that Kulle not be removed. Riddled with antisemitic tropes, the letter had harsh words for Lunin Schultz and Toperoff: “We are concerned that a small minority are acting immorally, ungodly, and unAmerican, trying to force their selfish, narrow pointed opinions on the rest of the community.” The writers contended that Kulle was being unfairly condemned “because he joined an organization over 45 years ago when he was 18 or 19 years of age.”

With a legal case ongoing, the letter said, there was “no justification for a small group to take the law into their own hands.” The letter characterized anti-Kulle sentiments as an “undemocratic … attitude of guilt by association” and asked the school board to judge the case “on the facts presented to the Federal government” and not “on the emotions of a small minority of citizens in Oak Park.” Though it argued that Kulle should be considered “innocent until proven guilty,” it also criticized the Coalition for an Informed and Responsible Citizenry for being “completely unforgiving.”

One of the first Oak Parkers to speak out publicly in Kulle’s defense was a student at the high school, who declared the head custodian “one reason to be proud of [the] school.” Toperoff was crushed when she saw the girl’s name in the Oak Leaves. Their families were friendly, and her son and the girl were close. The student argued that Kulle did not deserve “the mistreatment and verbal abuse that gets printed in the paper. … Mr. Kulle is a very kind and friendly man at school and I am sure that he is not proud of his Nazi background.”

Lunin Schultz had expected Kulle’s family, and even some friends and colleagues, to support him. But now the community’s children were standing up for a former concentration camp guard. Lunin Schultz was left deeply unsettled. What was happening at the high school?

She had barely calmed down the next day when she received a letter from John Lukehart, the idealistic chair of Oak Park’s Community Relations Commission. He thanked her and Toperoff for bringing the Kulle matter to the commission’s attention and attached a letter he had sent to the school board. “Mr. Kulle is a public employee, paid with public funds,” Lukehart wrote. “He is visible to the community in his present job. Given the above observations, it is the commission’s judgment that the Board of Education should put Mr. Kulle on a leave of absence immediately.”

Then Lukehart went a step further, beyond even what Lunin Schultz and Toperoff had called for: “The Community Relations Commission further believes that, should Mr. Kulle’s involvement as a member of the Nazi SS be substantiated, regardless of the outcome of the present judicial proceedings, the School Board should terminate his employment immediately.”

By now, Kulle was a constant topic of debate in the local papers, and both the Tribune and the Sun-Times had been covering the hearing. One of Kulle’s friends called Rich Deptuch, the beloved head of the school’s math department, to ask what the staff could do to help Kulle, and Deptuch agreed that it was time to make sure the school board knew how the faculty felt. Other teachers had approached Deptuch as well, hoping to help a friend. On at least one occasion a colleague expressed explicit antisemitism, and Deptuch immediately shut the conversation down. He would not tolerate bigotry. Nor was it his place to decide Kulle’s guilt.

In early November, Deptuch drafted a petition to the board stressing the “positive influence” Kulle had and arguing that “accusations of Reinhold’s alleged criminal misconduct as a member of the German SS nearly 40 years ago should have no bearing on his opportunity to continue to provide such valuable services to the school.” The final paragraph urged the school board to wait until a court ruling before making a decision regarding Kulle’s employment. Deptuch made several hundred copies of the petition at a local printer and distributed them in faculty mailboxes the next day.

One math teacher drafted a petition arguing that Kulle’s actions “nearly 40 years ago should have no bearing on his opportunity to continue to provide such valuable services to the school.”

Though the majority of the staff members were solidly in Kulle’s corner, there were exceptions. At a faculty meeting that fall, history teacher Michael Averbach had given an impassioned speech. It was not simply a legal case, he had said, or even a moral one; the school had a pedagogical responsibility to fire Kulle. “How can we tell kids that what they do at 16 or 17 matters,” he had pleaded, “if we say that what Reinhold did at 20 or 21 doesn’t?” Keeping Kulle employed, Averbach argued, would undermine everything the school claimed to be.

The school board had hoped that the legal system would take the decision out of its hand, but even now, after the hearing had ended and Kulle awaited a ruling, a fundraising note addressed to the “Friends of Reinhold Kulle” and asking for contributions to his defense made it clear that Kulle had no interest in a quick resolution. The case, it said, would “probably require appeal.”

That December, shortly before a school board meeting, Lunin Schultz, Toperoff, and a few others gathered to strategize. They needed to find a way to force the board to discuss Kulle in open session; the board had declared the matter a “personnel issue,” one that could be discussed only behind closed doors.

Back in October, Bruce Samuels had asked, almost sarcastically, whether the school had a policy about employees’ memberships in questionable organizations. What if, Lunin Schultz suggested, they asked the board to adopt a policy against employing former Nazis? There was something elegant about the idea. They would not mention Kulle by name. The discussion would remain theoretical, and the board would not be able to hide behind the “personnel issue” buffer.

The group had little interest in an actual policy — it seemed entirely unlikely that OPRF would be in this position again — but the proposal would box the school board into a corner. Driving home that evening, Lunin Schultz felt a weight coming off her chest.

There were few empty chairs at the next school board meeting. Lunin Schultz recognized many of the visitors, but the Kulle issue seemed to cast a wide net. Neo-Nazis were an increasing presence in front of the school, passing out booklets denying the Holocaust. Some of them even tried to speak on Kulle’s behalf at school board meetings, but lacking Oak Park addresses, they were denied.

The board and the administration took their seats just after 7:30 p.m. and proceeded with typical housekeeping. After agreeing to draft a letter of appreciation to a retiring engineer, the board ceded the floor to the superintendent. But the large crowd certainly had not come to hear him discuss the new geometry textbooks. The meeting continued with a long list of items — everything but Kulle.

Finally, it was time for public comments. Gignilliat, the school board president, issued a reminder that the board would hear discussion of policy but that personnel issues would be reserved for executive session. Toperoff tried to cover a wry smile as Michael Fleisher, a member of the Coalition for an Informed and Responsible Citizenry, rose to address the board.

The board’s refusal to take action, he asserted, jeopardized “the first obligation of the high school” — to train its students to make informed and moral decisions. After pushing for more specifics on a statement the board had made earlier about the school reviewing its Holocaust curriculum, Fleisher shifted to his group’s ultimate demand. “We urge action based on a moral principle,” he said. A recent statement by Gignilliat had said that the board would not act on the Kulle matter until it had all of the “relevant information.” “If you are awaiting a legal decision by a hearing officer and/or continue to see this as a narrow personnel matter, you have misunderstood the issue,” Fleisher said. “We request an answer: Should a person who has voluntarily served in the SS be considered a suitable employee of District 200?”

Fleisher handed the board members copies of his statement, which had 40 signatures at the bottom, and returned to his seat. A few other speakers followed him, but even as they talked, his words kept a firm hold on the room.

Some of the board members grew defensive, and the discussion began to unravel. William “Jay Jay” Turner, the only Black member of the school board, tried to reestablish order. Thanking Fleisher for his statement, he pointed out that the members of the Coalition for an Informed and Responsible Citizenry had taken time to formulate their ideas together, and the school board needed to do the same.

At 10:15 p.m., Turner moved for the board to go into closed session in Swanson’s office. Almost exactly a year earlier in this very room, Swanson had first learned of Kulle’s Nazi past from the Sun-Times article. Swanson, who had unsuccessfully urged Kulle to take an early retirement, could tell he was losing the board members’ support. Kulle was just “a simple sergeant,” he argued. “Why was he getting blamed for everything the Nazis did?”

It was now past midnight, nearly five hours after the meeting had begun. The board members were all haggard, emotional, and drained. Deptuch’s petition, Fleisher’s speech, and the continued increase in attendance at school board meetings made it clear to everyone in the room: A decision regarding Kulle’s employment had to be made, separate from the outcome of the legal case.

Deliberations resumed in the high school’s boardroom on the morning of January 14, 1984. Kulle was asked to attend, but before he arrived, one board member recounted a harrowing conversation he’d had with a former Gross-Rosen prisoner. Gignilliat was struck by the fact that the number of reported deaths at the camp was almost the same as the entire population of Oak Park.

At 9:20 a.m., Kulle joined the meeting with his attorney, who gave prepared remarks. The board members then took turns interviewing him.

“Tell us exactly how you feel,” one school board member asked Kulle, hoping for clarity. “I feel bad, very bad,” Kulle said. “I just wished we had won the war.”

Turner had been reading everything he could about Gross-Rosen and had grown convinced that Kulle was responsible for a lot of dastardly things. When his turn to interview Kulle came, he stared across the table and asked him whether he had seen prisoners. No, Kulle responded, he had been on the outskirts of the camp. Turner abruptly changed the subject: He asked how Kulle’s promotions at Gross-Rosen had affected his relationship with Gertrud’s father. Then he switched back, asking Kulle whether he had ever done anything kind for the prisoners. Kulle told Turner the same stories he had told in court: He had brought chickens to a prisoner once, given water to another.

Which was it? Turner thought. Had Kulle been away from the prisoners, or had he brought them gifts? It was all Turner needed to hear. Kulle was lying.

Other questions followed from other board members, but Kulle claimed to recall very little from Gross-Rosen.

Had he ever shot anyone?

“I don’t remember.”

Had he ever abused or tortured a prisoner?

“I don’t remember.”

Had he ever killed anyone?

“I don’t remember.”

Gignilliat found the answers eminently frustrating. Kulle was certainly not helping his cause. Killing someone seemed like a thing a man would remember.

Finally, board member Carl Dudley, a minister and professor at a nearby theological seminary, tried to break through. It had been a tense day, and the stress of the entire situation was wearing on everyone. “Reinhold, how do you feel? Do you feel guilty? Do you feel that the things you did were wrong?”

“Yah, yah, I feel bad. I feel bad about the whole situation,” he responded.

“Tell us exactly how you feel,” Dudley implored, hoping for some kind of clarity.

“I feel bad, very bad,” Kulle said. “I just wished we had won the war.”

An envelope addressed to Reinhold Kulle arrived at OPRF that January. Inside were two pension estimates from the Illinois Municipal Retirement Fund. They would prove instructive.

The policy proposal against employing Nazis had indeed boxed the school board into a corner, and Kulle’s answers to Dudley’s questions had done him no favors. One by one, school officials were coming to terms with the gravity of the situation. Gignilliat, who had long held out hope that they could weather the storm, now recognized that it would be impossible to retain Kulle.

Back in December the board had promised a response to Fleisher by its January 24 meeting, but as the meeting neared, no statement had been released. Growing impatient, Lunin Schultz and Toperoff distributed a note urging friends to attend the upcoming meeting, hoping their presence would help “bring about a sound policy on this issue.” Attached to the note was a petition from Fleisher requesting substantive responses to the questions he had raised at the previous meeting. He planned to speak again.

Finally, on January 18, the school board released a statement. In large part a response to Fleisher, it pushed back on the suggestion that the board adopt a resolution condemning racism and genocide, which “would imply that the board has not previously condemned those heinous ideas and acts.” Quoting board policies, the letter stressed the district’s commitment to both moral concerns and diversity and reiterated that an ongoing curriculum review was underway.

At the end of the statement, Gignilliat addressed the board’s decision process. These were complicated issues, he explained, and it was precisely because “the board is well aware of the impact this matter has had on our community” that it would “continue to seek counsel as needed, act with prudent deliberation, and resist attempts to precipitate a premature decision.” It would announce a final decision when members had all the necessary and relevant information and when they were sure they could do so without abridging Kulle’s rights.

Lunin Schultz could not understand what “necessary and relevant information” the board still needed. What new information could possibly come out?

But Gignilliat felt that a decision of this magnitude would have to be unanimous, and the board would need the administration’s support. It could not just summarily fire Kulle and move on — not after a quarter century of service. As important as it was to end what had become a public relations nightmare for the school, the board hoped to somehow avoid hurting Kulle financially. The two IMRF simulations provided some clarity. The first estimated Kulle’s pension if he retired at the end of the school year; the second if he waited two more years and retired in July 1986.

Over the next few days, Gignilliat, the school board, and the administration weighed their options. Quietly, slowly, carefully, they crafted a way out — one they would shroud in secrecy for decades.

On the evening of January 24, 1984, Toperoff waited nervously for the school board meeting to begin. Word had gotten out that the board planned to make an announcement about Kulle. To accommodate the large crowd that was expected, the board moved the meeting to one of the school’s auditoriums. Toperoff’s husband, Gil, sat on one side of her; Lunin Schultz and her husband, Richard, on the other. Friends were clustered in nearby rows. Herr Schoepko, the school’s German teacher and Kulle’s friend, settled into a seat behind them.

The room grew quiet. Oak Parkers were still filtering into the few remaining seats. After some formalities, Gignilliat announced that he was going to read a statement and that visitors would not be allowed to comment until later in the meeting.

Toperoff took a deep breath.

“In recent months,” Gignilliat began, “this board has devoted considerable time and attention to Reinhold Kulle’s employment in the district.”

The room was eerily quiet. Gignilliat read slowly and deliberately: “The board understands that under present law, no guard at a Nazi concentration camp would be permitted to immigrate to the United States.”

Toperoff looked to her husband, and to Lunin Schultz.

“As a member of the noncertified supervisory staff, Mr. Kulle does not have a written employment contract.”

The crowd was now becoming animated, whispers growing louder.

“The law does not compel the board either to reemploy or to terminate Mr. Kulle. The paramount considerations are and have been moral issues, including fairness to Mr. Kulle. Fairness to Mr. Kulle suggested to the board that it do nothing to interfere with his defense during the deportation hearing. The hearing has concluded. The board has obtained all the necessary relevant information, has been deliberate in its consideration, and is now prepared to act.”

Lunin Schultz tried to quell her frustration at the revisionist history of the last 13 months.

“The board is unwilling to show less than utter revulsion for the Nazi horrors. In making a decision, the board rejects any suggestion that to terminate Mr. Kulle’s employment involves notions of ‘guilt by association.’ It is not the board’s charge to decide whether Mr. Kulle is ‘guilty’ in that sense; nor does the board wish to prejudice his employment in the private sector. It is simply that no former guard at a Nazi concentration camp will be employed by this district. In a public school supported by public funds for educational purposes, the goal is to teach that each individual must accept responsibility for personal behavior and its implications for society.”

It was strong rhetoric, and the crowd was responding strongly as well. Around Toperoff there were smiles and tears of exhaustion; behind her, groans of frustration and murmurs of discontent.

“Accordingly,” Gignilliat continued, “Mr. Kulle will not be reemployed as of July 1, 1984, and is placed on terminal leave of absence effective January 25, 1984. Because the performance of his duties has given no legal cause to end his employment status or to cease compensating him, he will continue to receive his salary until June 30, 1984.”

Gignilliat moved back from the microphone. Toperoff stood up, applauding. So did Lunin Schultz and dozens of others.

It was over. Kulle was gone.

A group of Kulle’s friends a couple of rows away heckled loudly. “Where do these Jews come from? They rise from the ashes!”

Jeffrey Greenwald, a sophomore, stood with his parents and heard a scolding voice a few rows behind him: “Wir bleiben setzen.”

He turned around to see Herr Schoepko, the German teacher, and leaned over to his father, confused. “We stay seated,” his father translated.

Chills went down the boy’s spine.

The announcement had done exactly what the board had hoped. Kulle’s opponents were happy, and the board would soon be able to move on from the turmoil and return to its work running the school. Though Kulle’s colleagues would be upset, Swanson would be able to handle the faculty.

But Reinhold Kulle had not been fired. He would be allowed an early retirement, and the board would give him a severance package. School officials would work with the retirement fund and Kulle’s lawyers to find the best possible solution for his family. They would do their best to take care of him. It was a compromise between the board and the administration, a way of satisfying those who wanted Kulle gone and those who thought the school still owed him loyalty.

And it would all be kept quiet. There would be no additional public announcements. The board would be careful to discuss the topic only in closed session, and the notes from those meetings would be kept sealed for nearly 40 years — one of the high school’s best-kept secrets.

In November 1984, the judge in the deportation hearing finally issued her ruling. The evidence was “clear, convincing, and unequivocal,” she wrote, that Reinhold Kulle had participated in persecution under the direction of the Nazi Reich.

After a series of failed appeals, Kulle was taken into custody at his Brookfield home on a Friday night in October 1987. The following Monday, he was put on a plane to Germany. Once there, he headed to a relative’s home in Lahr, the city he had left 30 years earlier. West Germany’s chief Nazi crimes prosecutor announced that Kulle would not face charges; a preliminary investigation had turned up “no indications of a crime that can still be prosecuted.”

After a few years, Kulle lost touch with most of his friends from Oak Park, though a reminder of his time at OPRF came in the mail each month in the form of a pension check from the Illinois Municipal Retirement Fund. Those payments stopped in 2006, when Reinhold Kulle died in Germany, at the age of 85, still a free man.

Adapted from Our Nazi: An American Suburb’s Encounter With Evil by Michael Soffer, with permission from the University of Chicago Press. © 2024 by the University of Chicago. All rights reserved.

Related Content