The Cubs set a lot of pieces in motion over the past few years—some of which can be credited to Theo Epstein's predecessor, Jim Hendry—that virtually all clicked last year, some as expected, some far better. One exception was one of the biggest and most expensive: Jason Heyward, who hit a ghastly .230/.306/.325 after signing an eight-year, $184 million contract.

He was still arguably a decent player thanks to his superlative defense—Fangraphs has him at 1.6 wins above replacement, though Baseball Prospectus has him at exactly replacement-level—and his unquantifiable Game 7 rain-delay speech, but he was far from what the Cubs paid for. Even a two-win player at $23 million per year would be a big overpay, as WAR per year, as of 2015, was going at about $8 million.

But Heyward's line as of yesterday is a vastly improved .296/.367/.370. It's a good average and a great on-base percentage, though without much power yet (eight hits, just one for extra bases, a triple). It's a small sample size, and there are some issues within it, but it has people paying attention to his new swing.

I first noticed it thanks to Fangraphs' excellent new hire Travis Sawchik, a former Pirates beat reporter and author of a book about the team's reinvention, Big Data Baseball. He pointed to a piece by Fox's well-connected Ken Rosenthal about how the Cubs have revamped it, while grabbing some video captures and looking at the results in terms of exit velocity. Heyward's made a big change, and the early results are encouraging.

Here's a screengrab of Heyward as a Cardinal from April 17, 2015:

And as a Cub from July 16 of last year:

And from last night:

He's dropped his hands way down. By contrast, here's Heyward in 2013, as a Brave:

This decision lines up with something Fangraphs' Jeff Sullivan found in a wonderfully thorough piece last year: Heyward used to be a good low-ball hitter, and in 2016 he switched to swinging at pitches up in the zone. "Put another way: he’s swung more often in areas where he’s been historically weak, and he’s swung less often in areas where he’s been historically strong," Sullivan wrote. "These are the weird decisions."

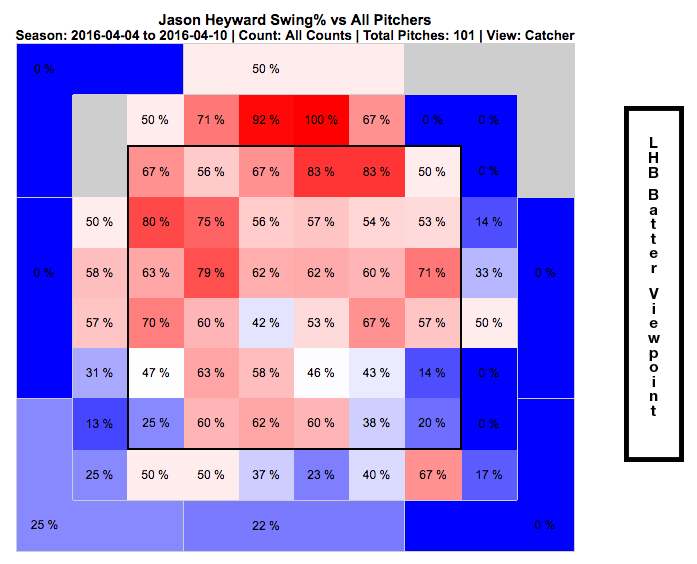

And Heyward seems to be going back to his old approach. Here are his swings through his first 101 pitches last year:

And his first 103 this year:

There's another aspect to Heyward's swing that Eno Sarris described in Februrary of this year: Heyward's hands being so close to his body last year made it harder to hit inside pitches. "If you’re that far in, your first move has to be away from your body," Sarris wrote. "And then back. That creates another step, and more time in between the beginning of your swing and contact. That could hurt you, especially on pitches inside." And he documented the hurt—in particular, that pitchers attacked Heyward inside.

And that seems to be working out, too. His average per pitch over the same timeframe last year:

In the same timeframe, for the times Heyward's hit the ball and for which we have Statcast data for, his average exit velocity is up about six miles an hour. It's a tiny sample, but if he sustains it, that would be a very good increase.

Again, it's a small sample size, and there are some things that aren't sustainable about the current numbers (.348 batting average on balls in play, compared to a career .303, and a high percentage of infield hits). It's possible that a new swing will create new problems, but at the same time he seems to be addressing last year's problems.