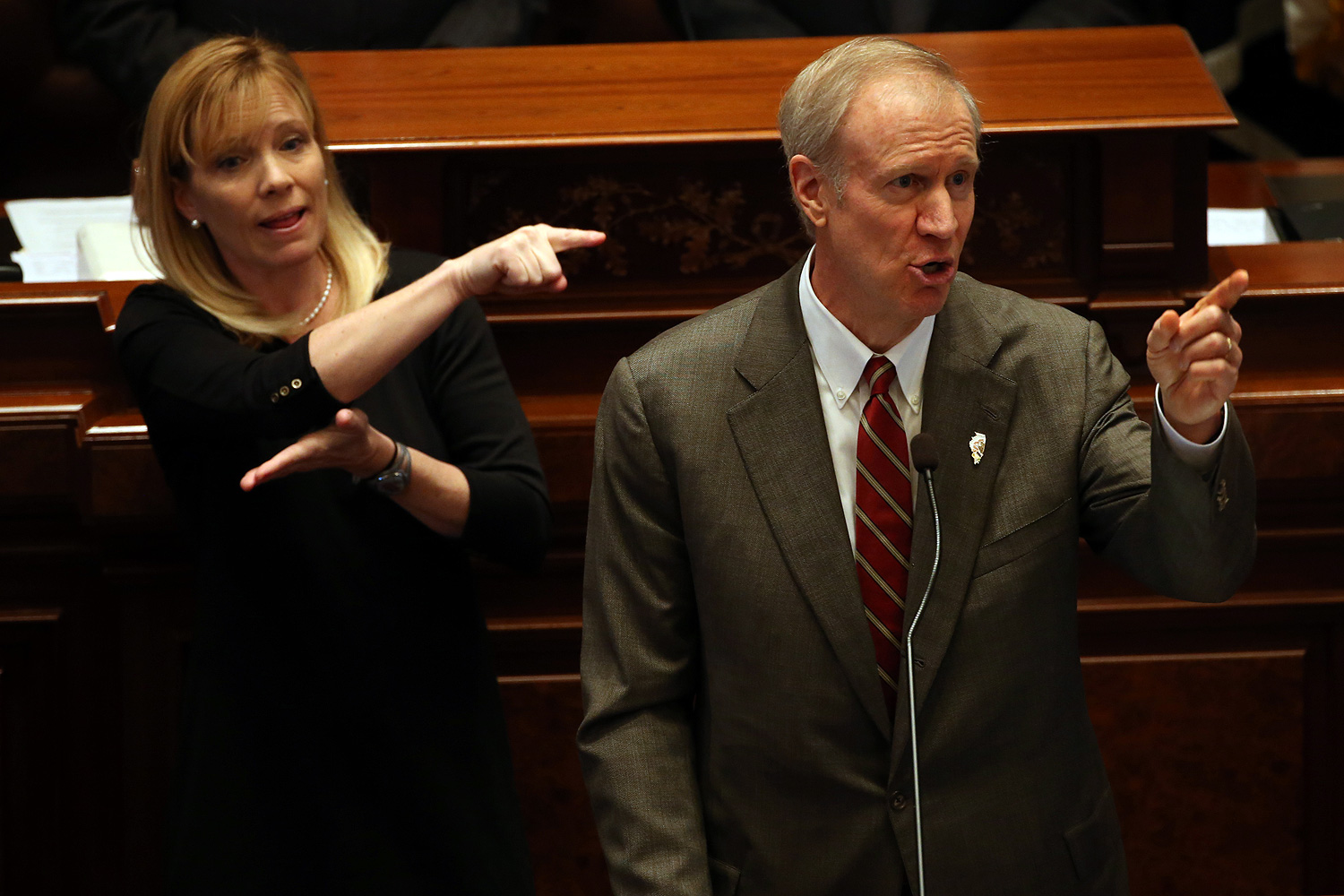

The budget proposed by Bruce Rauner yesterday contains a lot of targets, big and small—huge cuts to higher-ed funding; to the CTA, Metra, and Pace (including support for paratransit); to Medicaid, including dental services for the poor (which was brought back after the last round of cuts); support for wards of the state after the age of 18; and a long list of social services and educational programs.

It's a lot. So I asked Rep. Elaine Nekritz, one of the legislative leaders on pension reform for years now, what surprised her the most. It wasn't the cuts.

"I was intrigued that the governor started out by saying that the General Assembly had, for years, been doing basically fake, unbalanced budgets—and then proceeded to use the potential for pension savings to balance his budget. Which seemed to run completely counter to the way he started his speech," Nekritz said.

Those $2.2 billion in savings are, in fact, a very big "if." Not only would the timetable for a legal challenge to the Pension Code have to be accelerated, it relies on a pretty big assumption that, even if the challenge could be mounted, it would pass muster with the state Supremes.

Rauner's pension savings are based, in large part, on moving most existing state workers from their current Tier I status into the less generous Tier II system: "the pension reform plan protects every dollar of benefits earned. What you’ve earned, you’re going to get…. But moving forward, all future work will be under the Tier 2 pension plan, except for our police and firefighters."

(For those new to pension talk, Tier I refers to employees who were hired prior to January 1, 2011. Tier II refers to newer employees, who were hired under a different, and less generous, pension deal that the state enacted.)

Sounds simple, right? It's not. It depends on what you mean by earned, and specifically what the courts think that word means in the context of the state pension code, and the legislative process that produced it.

About five years ago, the big law firm Sidley Austin—on behalf of the Commercial Club of Chicago—tried to come up with a legal argument that would support, in essence, what Rauner wants (emphasis theirs):

An increasingly important question is whether a prospective diminishment in pension benefits — meaning a diminishment that applies only to an employee’s future service, not to benefits already accrued from the employee’s prior service — causes a pension benefit to be “diminished or repaired.” The answer is No. Four years after the 1970 Constitution, the Supreme Court held that “the purpose and intent of the constitutional provision was to insure that pension rights of public employees which had been earned should not be ‘diminished or impaired’ … .” Peters v. City of Springfield, 57 Ill. 2d 142, 152 (1974) …. Thus, the only pension benefits protected from diminishment are those “which had been earned” at the time the pension scheme is altered. Pension benefits earned in the past cannot be reduced, while benefits that the employee hopes to earn in the future can be reduced.

Benefits that have been earned aren't in dispute—it's a question of when those benefits are earned. And in a long, thorough analysis by Eric Madiar, chief legal counsel to John Cullerton, the existing case law heavily suggests that those benefits are "earned" when a state employee starts work and begins to contribute into the pension system.

Peters v. Springfield isn't a particularly good case to hang the argument on. It involved a fireman who claimed his pension benefits were diminished when the mandatory retirement age was changed from 63 to 60. Pension laws don't, and obviously shouldn't, govern things like when a firefighter has to retire. (He lost.)

Closer to what Rauner intends to do is Kraus v. Niles. In short: a cop was injured, in 1967, and went on disability. At that time, if he did 20 years of service—including disability—and reached the age of 50, he could retire with a 50 percent pension based on his salary at the time of retirement.

But in 1973, the General Assembly decided that cops in that situation would get a pension based on the time they went on disability, not on when they retired. Three years later he retired and asked for the pension he was expecting. And got it.

Madiar explains (emphasis mine):

The court then stated its holding was supported by New York court interpretations of that state’s identical constitutional provision. Further, reliance on New York cases was appropriate because the drafters intended for the Pension Clause to follow the results of the New York provision. These cases, according to the court, made clear that employee pension rights became fixed as of the time the employee entered the pension system or the time the constitutional amendment became operative, whichever is later, but not at the time of retirement.

The court also took particular notice of Kleinfeldt v. New York—as would the Illinois Supreme Court in 1985—where the New York court of appeals held that a statute adversely changing the salary base on which retirement benefits were computed could not be constitutionally applied to those who became members of the system prior to the statute’s effective date. Because the drafters modeled the Pension Clause after New York’s, the court distinguished the Clause from the constitutional provisions of Alaska, Hawaii, and Michigan, which only safeguarded pension benefits that had been "accrued."

So when Rauner says What you’ve earned, you’re going to get, the case law seems to make a big distinction between earned and accrued.

There's a further uphill battle. As Madiar goes to great lengths to demonstrate, the impetus for Illinois's very strict legal protections for state employee pensions came about because the state was doing a crap job of funding pension systems. Employees were worried that the state would do… well, exactly what it's doing now.

These requests were renewed in a June 26, 1970, letter received by all convention delegates from Harl H. Ray, chairman of the Employees Advisory Committee to the State Universities Retirement System. Mr. Ray implored delegates to “not deny us the Constitutional right to always be able to receive that pension promised by the State Legislature during our period of employment.” Constitutional protection, he reasoned, was warranted because “the State Legislature has failed to finance the pension obligations on a sound basis.”

Granted, this is law—in theory, Rauner could get his way. The Supremes could decide that Illinois is sufficiently screwed as to allow the state to use its police powers to diminish pension plans, in order to protect the pension systems or the state's ability to provide basic services (though Madiar is skeptical of that, too). It's possible, it just seems extremely unlikely.

Moving employees into Tier II isn't Rauner's only idea for pension savings: "This budget also gives employees hired before 2011 a choice to take a buyout option—a lump sum payment and a defined contribution plan in return for a voluntary reduction in cost-of-living adjustments."

That would be fine. Pension benefits are contractual, and this is a perfect example of what's permitted: diminishing benefits in exchange for "consideration," in this case, a lump-sum payment. And it could result in savings.

"The buyout, I think, has some potential," Nekritz says, "but the devil's in the details—what are you buying people out of? We actually talked about that. Would we want to buy people out of a particular portion of a benefit? Would we want to buy them out of their future COLA? Or a portion of their COLA? Or something else? Because, I think, the data would show that most people really undervalue the future benefit. They're much more willing to take cash today versus the value of that benefit in the future. Pay me now instead of pay me later. That has happened in the private sector, and it's been really successful in reducing unfunded liability. But, again, the devil would be in the details."

But it's also hard to predict how much a buyout would save.

"We went through a lot of this on the various iterations of the pension reform bills that we were proposing," Nekritz said. "There you had to make a lot of assumptions that choices people would make. The actuaries just look at you and say, 'we're not sociologists, we're not psychologists, we have no idea what choices people would make.'"

If all that sounds bad, it's really important to keep one thing in mind, as Rich Miller reminds us—Governor Rauner can't include potential new revenues from tax reform in the budget. As Nekritz explained, this rule was created in response to Rod Blagojevich's "if a miracle occurs" budgets. That's why many are skeptical of the assumed pension-reform savings, but it also means that the doomsday nature of the budget could be ameliorated by tax reforms that could help but can't be factored in.

None of those ideas came up in the budget address, where Rauner could have at least mentioned them, but he did campaign on them—fairly specific proposals for expanding the state's sales tax on services, and less specific proposals for closing tax loopholes. It'll be a real test of the state's newly divided government.

"If the governor is intent on having no new revenue, which is certainly the way he presented his budget, and the way he's been talking, it's hard enough to get 60 votes in the House on these proposals," Nekritz said. "We have to find a veto-proof majority. It's a very difficult challenge. I don't think there are 71 Democrats who are willing to vote for a revenue increase. The veto-proof majority, in a lot of ways, is a myth. It might be on process matters, but on policy matters, I don't think 71 of us agree on anything."