From the racist rhetoric of his campaign to the appointment of white supremacist Steve Bannon as his chief strategist, Donald Trump’s election has emboldened white nationalist groups that were once considered fringe. When his victory brought “Hail Trump” cheers and Nazi salutes from the crowd at the National Policy Institute’s Nov. 19 meeting in Washington. D.C., many of Trump’s detractors feared the worst—a return of Nazi ideology to mainstream America.

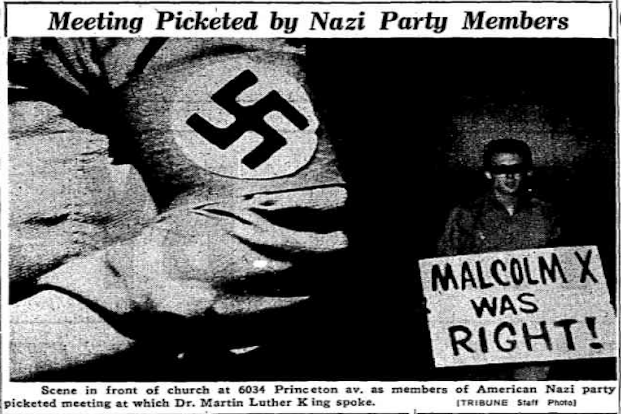

In fact, it hasn’t been so long since that particular blend of anti-Semitism, racism, and misogyny held sway even in deep-blue Chicago. Decades after Hitler was defeated in Europe, the National Socialist Party of America (an offshoot of the American Nazi Party) had a stronghold in Chicago’s Marquette Park in the 1970s, where it mostly focused on anti-black policies. The sentiment was not fringe at the time; we previously wrote about how, in the mid-20th century, especially in reaction to Martin Luther King Jr.'s campaign for fair housing, mobs of thousands of white people in Chicago violently tried to stop blacks from moving into majority-white neighborhoods.

NSPA head Frank Collin was perhaps most famous for a landmark 1978 U.S. Supreme Court case in which the group fought for the right to protest in front of Skokie’s city hall, a wildly unpopular move as the suburb had a large Jewish population, including many Holocaust survivors.

David Goldberger, professor of law of Jewish heritage at Ohio State University, argued on Collin’s behalf while working for the American Civil Liberties Union. Here’s what Goldberger had to say about why the Nazis settled in Chicago, his First Amendment role, and his thoughts on Chicago’s future.

What factors in Chicago led to this Nazi group taking shape in Chicago?

Collin managed to buy a place in the Marquette Park area. His building was in a Lithuanian neighborhood. To the east of that neighborhood, [Englewood] had been a changing neighborhood and was becoming solidly black. The homes in the Marquette Park area were turning over. There was a sense that the transition from white to black was spreading, and that made, I think, the NSPA an increasingly appealing group.

How did the Chicago Housing Authority indirectly help segregation in the city as the Nazis wanted?

It was clear that public housing was needed, and Mayor [Richard M.] Daley located the housing developments in places where it was pretty clear that you could concentrate minorities. There would be natural barriers for the minorities then to spread, for example the Dan Ryan Expressway. I think if you look at the location of the housing projects that went up, they were all located in black communities so that would increase the concentration because they were very high density operations.

How did Chicagoans initially react to the Nazis?

That’s hard to say. It seemed to me in the Marquette Park area they were quite tolerant. I don’t want to say farther than that. The black community, needless to say, was hostile because the NSPA was focused on race as opposed to going after Jews, although Jews were on its agenda. The black neighborhoods in Englewood and the neighboring areas understood what was what. I think as you move north, there was indifference. [The Nazis] were regarded as a curiosity, an offensive curiosity, but a curiosity nonetheless.

How did you get involved in the controversy with the NSPA?

The Chicago Park district began to block [Collin’s] access [to public spaces]. He came to the ACLU, and we sued the Chicago Park District successfully to have that restriction invalidated. He then asked us to represent him in dealing with getting a permit to hold a parade. Our position at the ACLU was he has a First Amendment right, so we basically represented him in getting the permit. [After he was arrested for marching,] we represented him in criminal proceedings. He was acquitted because it was pretty clear to the judge—who had the guts to do it, I must say—that it was classic First Amendment activity.

Following that, Collin was blocked out of all parks. We sued the Chicago Park District to get him back in Marquette Park. There was going to be a hearing because now the Park District wanted Collin to obtain insurance, and no insurance company in its right mind was going to write the insurance. As a consequence, Collin began to apply to park districts throughout the suburbs to hold assemblies.

I went home [one day], and I got a phone call from Collin saying, “I’ve been planning to go hold an assembly in downtown Skokie because I’ve been refused a permit by the Skokie Park District, and I was just served with papers that I’m to appear in court tomorrow because they’re going to try enjoin my march.”

How did you feel arguing that case?

Well, to be perfectly honest, I was a pretty stubborn First Amendment lawyer. What Collin wanted was to engage in pristine First Amendment activity. At that point, I had no indication of any interest in violence or any desire to get arrested or anything like that. I wasn’t wild about it, but it seemed to me that if I had any respect for the First Amendment, it was a slam dunk and you did it. And if I didn’t want to do it, then it was time for me to look for a new occupation.

Do you see any current issues in Chicago today that could pave the way to a resurgence of Nazi-like sentiments?

Before the Trump election, I would’ve said there’s very little that will happen, but it’s conceivable. I don’t know at this point statistically what part of the reactive white community that’s left in Chicago as a proportion of the population, but I mean, we know that there’s a segment of the Chicago population that’s attracted to populism. It seems to me the Black Lives Matter movement has provoked a reaction. I think that really helped Trump. In spite of the fact, I hope the kids don’t give up on it. But that [backlash] could crystallize the reemergence of that kind of extremist movement. It's got to be a reaction to something, such as the black shootings of white police officers. People get angry and hostile to start with and they're looking for a reason to coalesce and feel like they're part of a victimized community. And I'm not talking about blacks. I'm talking about a segment of the white community that feels victimized.