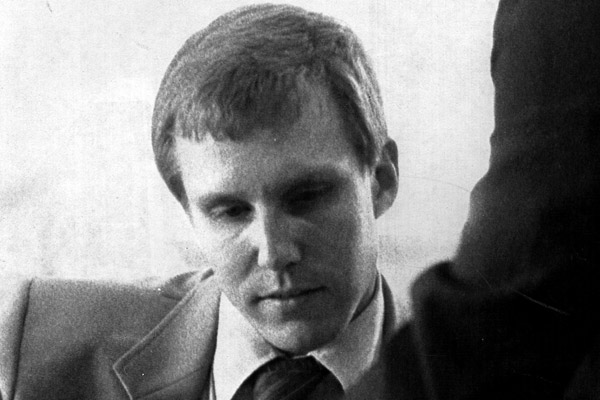

Chicago Tribune file photo

Michael Swango (shown in 1985) was able to commit brazen, terrible crimes under weak regulatory control and a lack of attention from the media. With Dr. Kermit Gosnell, on trial now, is history repeating itself?

In 2011, a Philadelphia abortion doctor named Kermit Gosnell was charged with eight counts of murder—one for a woman who died in his clinic in the West Philadelphia neighborhood of Mantua, seven for the deaths of newborns who were killed outside of the womb. The case was laid out in a disturbing, lengthy grand jury report that addressed not only Gosnell's alleged crimes, but his history as a doctor going back to the 1970s.

The horrors of the Women's Medical Society went well beyond the murder charges. There were illegal late-term abortions and incomprehensibly unsanitary conditions—fetal remains in the staff refrigerator, bloodstained equipment, sick cats defecating in the halls. There were a total lack of medical standards, like a broken EKG and defillibrator, and the unmonitored, non-standardized use of dangerous, outdated sedatives. The personnel included no registered nurses, but there was a 15-year-old who sedated patients. Some findings were simply beyond understanding—the doctor kept the feet of fetuses in jars in the office.

The facility went uninspected by the state for 15 years, a fact as incomprehensible as the accusations against Gosnell.

You may have missed the news of this. There was some coverage, particularly in the feminist blogosphere, and Philadelphian Jeff Deeney wrote what's still the best piece on it back in 2011. But the perceived lack of national coverage is becoming a flashpoint again during the ongoing trial, which began a few weeks ago. It seems to have started with an op-ed in USA Today: "The deafening silence of too much of the media, once a force for justice in America, is a disgrace."

For Chicagoans, there is an old, disturbing local connection: "On Mother’s Day weekend in 1972, Karman, other activists, and 15 women in their second trimester of pregnancy boarded a bus in Chicago and headed for Philadelphia, where Dr. Kermit Gosnell had agreed to give them super-coil abortions at his clinic, then at 133 S. 36th St. The women, who were poor, had been unable to get abortions in Chicago or New York. Gosnell’s super-coil abortions—filmed and later shown on a New York City educational-TV program, thanks to [California psychologist Harvey] Karman—turned out badly. The federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Philadelphia Department of Public Health subsequently did an investigation that detailed serious complications suffered by nine of the 15 women, including one who needed a hysterectomy. The complications included a punctured uterus, hemorrhage, infections, and retained fetal remains."

In The Story of Jane: The Legendary Underground Feminist Abortion Service, Laura Kaplan describes the scene around the Chicago-to-Philadelphia bus trip, and the tensions it caused within the pro-choice community.

Melinda Henneberger of the Washington Post wrote: "One colleague viewed Gosnell’s alleged atrocities as a local crime story, though I can’t think of another mass murder, with hundreds of victims, that we ever saw that way."

* * *

One such story came to mind, about a doctor who killed multiple patients, though no one knows how many. In the annals of Illinois crime, it's one of the worst cases I know of.

Michael Swango grew up in Quincy, Illinois and went to Southern Illinois for medical school. The journalist James B. Stewart, a Quincy native, estimates in his book Blind Eye that Swango killed 35 people as a medical student and doctor, though in the end Swango only admitted to four and received a life sentence for three of them:

The pattern, then and in the 15 years to come, was generally the same: a late-night visit by Swango, usually unobserved, to a patient's hospital room, some injection into IV lines and sudden death for a patient who had been expected to recover. The victims were men and women, young and old—and apparently chosen at random. Stewart reports that his research has found circumstantial evidence linking Swango to the deaths of five patients at Southern Illinois University, five at Ohio State Medical Center and five at the Veterans Administration Hospital in Northport, N.Y., where Swango managed to find employment despite the trail of death behind him. Fleeing to practice in the relative anonymity of Zimbabwe, Stewart says, he evidently killed 20 more people there.

Blind Eye is a fascinating book, but it's unusual as a true-crime work; much of it is about the regulatory failures that allowed Swango to continue practicing, failures that had less to do with rules than the unwillingness of those in power to exercise common sense when presented with something well out of the ordinary, or to listen to knowledgable colleagues.

When Swango was at SIU, he was caught falsifying patient information, demonstrated patterns of extreme incompetence, and, while working as an ambulance tech, was prevented from having direct patient contact. Swango was nearly expelled, and graduated late. Five patients that were given histories and physicals by Swango died, earning him the nickname "Double-0 Swango"—a license to kill. No one actually thought that Swango was a killer, but as Stewart writes, five of his classmates wrote a letter urging that Swango be expelled: "None of the group felt they would ever want Swango to be a doctor."

Swango barely got through SIU, and the dean of SIU's medical school noted his academic and behavioral issues in a dean's letter. But he still got a internship in neurosurgery at Ohio State, one of the most prestigious appointments in the country for one of the most prestigious practices in all of medicine—because no one read his dean's letter, and no one at OSU actually talked to anyone at SIU. Swango set off the same alarms, exhibited the same patterns, and committed the first of the murders he later admitted to.

And no one knows how long Swango would have continued to kill Ohio State patients; he was eventually caught and sent to jail, not by OSU (who circled the wagons), but by law enforcement in Illinois. During the summer of 1984, Swango took a job as a paramedic back in Quincy, and poisoned his co-workers—non-fatally, on several occasions. They set a trap, arranged for a friendly Quincy College chemistry professor to test it independently for arsenic, and then finally moved on to the Illinois Bureau of Investigation.

Swango had killed at least one person by then, likely more, as a doctor, raising the vague suspicion of colleagues and the direct suspicion of OSU nurses, whose concerns were dismissed. But it was a group of paramedics—not the many doctors Swango worked with—who recognized the pattern, collected the evidence, and got him arrested.

Meanwhile, Swango applied for a job as an emergency room physician: "Even though Swango was at that very moment once again under investigation, and Ohio State officials knew he had been charged with poisoning coworkers in Illinois, the university gave National Emergency Service a certificate showing that Swango had satisfactorily completed his internship." He got the job. It wasn't until a member of the Ohio State Medical Board tipped off the Cleveland Plain Dealer that anything about Swango made it outside the self-protecting bureaucracy. It wasn't until 1986 that Swango's licenses to practice medicine were suspended in Ohio and Illinois—just before and just after Swango, then serving a five-year sentence for the poisonings, was the subject of a segment on ABC's 20/20, "the first national exposure Swango received."

He served two years. A few years later, he managed to get a job as a resident at the University of South Dakota, which later found out about his past only because an American Medical Association staffer happened to know the USD medical dean, and because the 20/20 segment happened to air on the Discovery Channel program Justice Files.

Swango was dismissed from USD… and promptly got a job as a psychiatric (!) resident at SUNY-Stony Brook:

Unlike administrators at South Dakota, SUNY officials didn't contact the Federation of State Medical Boards, so they weren't aware that Swango's licenses had been suspended in Ohio and Illinois. As in South Dakota, there's no indication anyone knew the National Practicioner Data Bank was in operation. Nor did it occur to anyone to check with judicial or prison authorities or with the police about the battery conviction that Swango admitted [he said it was a bar fight], or even to find out what Swango had been doing in the years since his release from prison. He told them nothing of his aborted residency in South Dakota.

Once Swango's past caught up with him there—not through official channels, but because his late wife's parents learned that he had become a doctor somewhere in New York, and alerted a USD nurse, who told the USD dean, who found Swango at Stony Brook—that finally ended Swango's medical career in the United States.

He escaped to Zimbabwe at the end of 1994, under the assumption that the lax oversight of a third-world country would give him cover. But Zimbabwe nurses and doctors were comparatively diligent. Nurses brought their suspicions to the doctors, who went to the police. Swango was forced to leave Zimbabwe, and Africa altogether after Zimbabwean authorities put out a region-wide alert to hospitals. When trying to secure a U.S. visa in order to work in a hospital in Saudi Arabia, Swango was finally arrested while on a transfer at O'Hare. The FBI estimates Swango killed up to 60 people.

* * *

The Gosnell case immediately reminded me of Michael Swango, not just because both were doctors and committed their crimes (some still alleged) in medical clinics, but because both were able to commit them because of incomprehensible regulatory failure. Rather than operating on the margins of society, Swango murdered in plain sight, in one of the most tightly regulated and rigidly systematic environments in American culture. Nonetheless, those structures were not strong enough to overcome the willingness of people not to look.

And Swango, like Gosnell, just didn't get the sort of coverage you would expect from the magnitude of his crimes. And in Swango's case, it would have been fully justified: beyond just a horror show, Swango's case highlighted systematic failures that, if addressed, could prevent more common forms of malpractice. But there wasn't that much of it. The New York Times devoted a couple articles (there were more, after Stewart's book); even the longer piece from the trial, by an excellent reporter, Charlie LeDuff, barely scratched the surface of the case, even though the resources were out there for more (the late investigative reporter Gary Webb, for instance, covered Swango in the Plain Dealer after the mess at Ohio State).

The Trib archives list 24 articles about Swango, but 16 are from 1986 or before, when Swango was merely a poisoner, not a suspected and then convicted serial killer. When Swango finally received his life sentence in 1999 (he's now housed in ADX Florence, the highest-security prison in America, along with the Unabomber, Robert Hanssen, and Jeff Fort), it merited a scant 404 words on page three.

I tend to have some, um, interest in crime stories. So I'd heard of Swango and read Stewart's book. But I don't get the impression many people know who Swango is, though he may have been one of the most prolific serial killers in history, and one whose crimes tapped into a place where we feel most vulnerable.

Why did the cases of Gosnell and Swango not capture the attention of the public, and of lots of journalists? I wish I knew. (If I knew exactly what audiences and professionals desired, I'd be much wealthier.) I don't entirely believe that the lack of interest in Gosnell is that it was merely a "local crime story." On some level it is, but it's a shocking crime story in a big city. And not just any big city, but a tributary of America's media capital.

I don't buy Henneberger's argument that left-wing journalists are afraid to cover Gosnell because it reflects badly on the pro-choice movement: "There’s no mystery about where Gosnell could have gotten the idea that his youngest victims weren’t human, or entitled to any protection under the law." Because they haven't been.

* * *

A couple of years ago, Bill James, the famous baseball analyst who revolutionized the statistical approach to the game, wrote a long book on his other obsession, called Popular Crime: Reflections on the Celebration of Violence. James, like a lot of people, has something of an obsession with famous crimes and books about them, and the result is a thick brain dump of everything James thinks about famous crimes. It's a weird, idiosyncratic, and flawed book, but James's personal obsession with "popular" crime is an interesting lens to view the lack of interest in Gosnell and Swango.

James suggests four elements that cause regular crimes to become popular: careful planning, wealthy and attractive participants, a twisting narrative, and bold characters. The cases above contain none of these, except for wealth. Gosnell made a lot of money—that's why he did what he did—but his patients were poor and he practiced in a poor neighborhood. Gosnell (allegedly) and Swango simply did evil things for years, evading minimal enforcement with minimal effort. Neither were criminal masterminds; quite the opposite. There are no missing victims; no tangled motives and relationships. They just killed people they were disassociated from.

Sometimes—usually—luridness isn't enough. People are storytellers; they respond to narrative and suspense. (Not as much to state-level regulatory failure. I've tried.)

At the Atlantic, Conor Friedersdorf ran through 14 theories as to why Gosnell's case received so little coverage. Friedersdorf writes about politics almost exclusively, and his theories are basically all political—no one will write it because it's about abortion, because it's about poor black people, etc.

Some I don't think are wrong, but I bring up the Swango case to take it out of the political realm. The Swango case is similar in a lot of ways, but it's completely stripped of the Gosnell case's ideological charge: similar narrative structure, similar ramifications, similar scant attention. Not everything is political. People most of all.