The death of Dr. Donald Liu and one other man—and perhaps a third—in Lake Michigan this weekend turned a focus on rip currents this week (yes, I grew up saying "riptide" and "undertow" too, but "rip current" actually describes the phenomenon better):

Although they can be hazardous to swimmers off the beaches of Chicago and the North Shore, they are more common along the shoreline of Indiana and southwest Michigan, where a mix of wind, waves and sandbars can turn picturesque vistas into deathtraps. The weather service has identified the region as one of the most dangerous areas for rip currents in the Great Lakes.

More than that, it's one of the more dangerous places in the country by fatalities, from 1994-2007:

Where do they come from and why are they so bad? Well, the science on it only starts in the '30s and '40s, rip-current forecasting has only been around two decades, and because the conditions creating them are short-lived, the research on them isn't vast. But notice where the most fatalities are in Lake Michigan: on the eastern coast, at the widest part of the lake. Basically a rip current happens when a bunch of water goes on shore and then back out again—a lot of kinetic energy builds up, and it bursts through breaks in sandbars. Wind pushes water, and winds generally go west-to-east across Lake Michigan (which is why the dunes are there). The wind pushes it to shore, and it finds its way back through rip currents.

Middle Bay, Marquette, Michigan, from NOAA

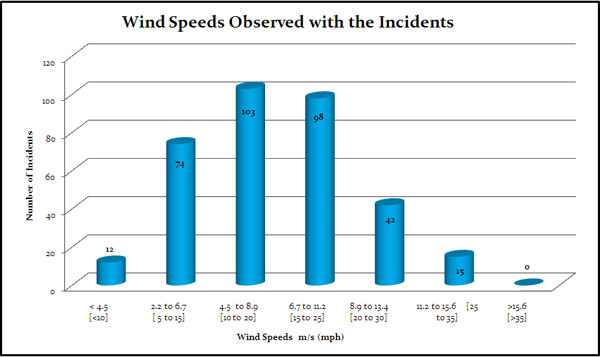

And it really doesn't take unusual weather conditions to create rip tides. Most incidents happen during moderate conditions—low wave heights and moderately high wind speeds, because there's enough wind to create rip currents but not so much that people aren't swimming:

But don't take it from me: take it from a grandfatherly scientist with a subtle Southern accent; that always helps me understand things.