Caleb Williams, the Bears’ No. 1 draft pick, has already been proclaimed the greatest quarterback in the team’s history.

“Williams is the total package, blessed with extraordinary arm talent, field vision, pocket awareness and running ability,” wrote the Tribune’s Dan Wiederer. “To top it all off, his creative playmaking artistry as a passer is what many talent evaluators identify as his superpower…This isn’t Mitch Trubisky. This isn’t Justin Fields…Chicago has not witnessed anything like this.”

In the history of the National Football League, no team has been weaker at quarterback than the Bears. They have as deep a history as any team, but a shallower QB pool. Their all-time leading passer is Jay Cutler, with 23,433 yards, ahead of only the Texans’ Matt Schaub and the Buccaneers’ Jameis Winston. Their Super Bowl-winning quarterback, Jim McMahon, is not in the Hall of Fame, unlike most Super Bowl QBs. The defense won that Super Bowl. Defense, not offense, has always been the Bears’ forte, Matt Forte notwithstanding.

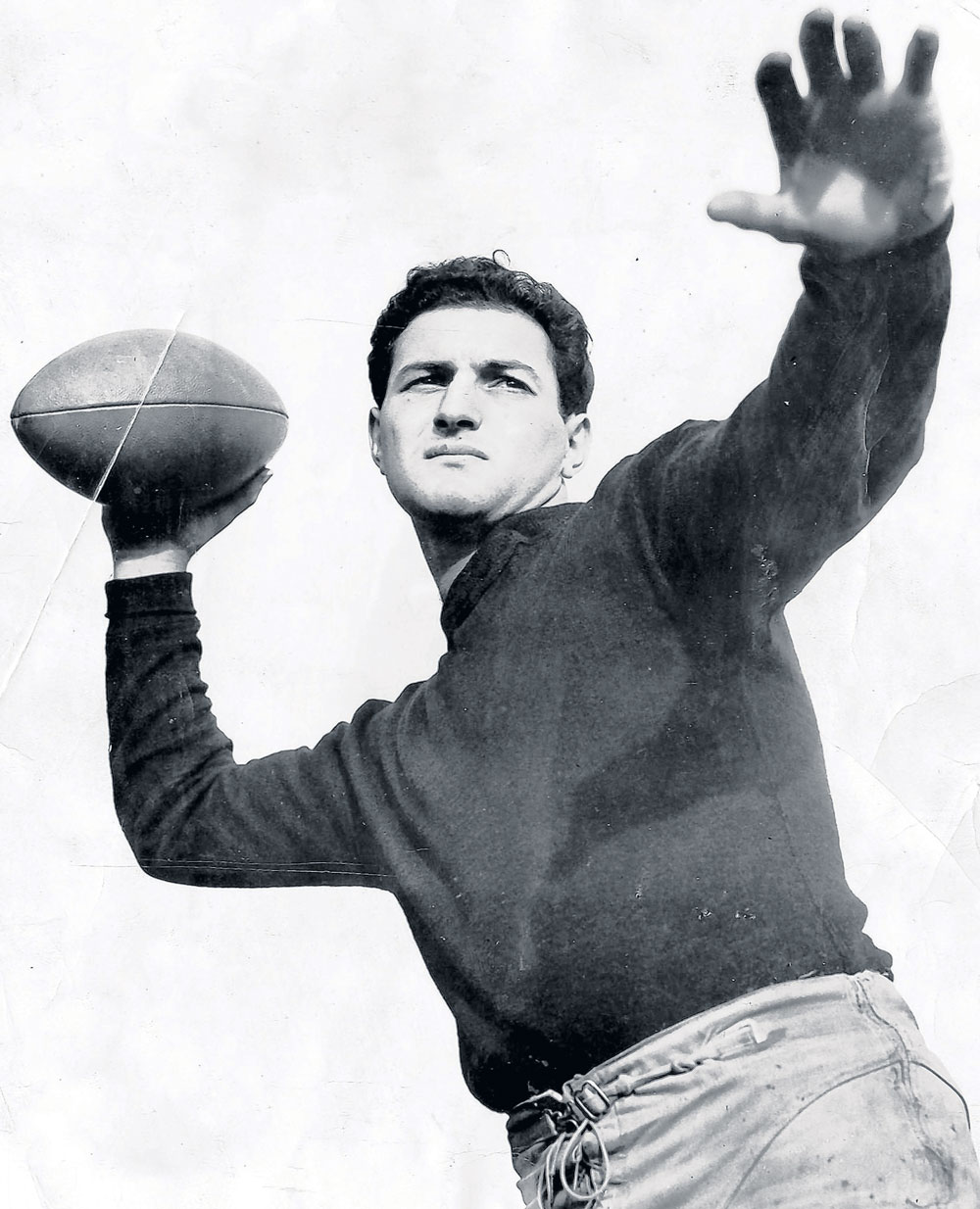

To fulfill his promise, Williams has only one man to beat: Sid Luckman. It’s hard to say he has to make Bears fans forget about Luckman, because most have already forgotten about him, since he retired in 1950. But the team ranks him No. 4 on its list of greatest players, after only Walter Payton, Dick Butkus, and Bronko Nagurski. In 2010, the NFL named Luckman the 33rd greatest player of all time.

On paper, Luckman’s achievements do not look impressive to the modern fan. He only completed 51.8 percent of his passes. He threw almost as many interceptions (132) as touchdowns (137). His lifetime passer rating was 75.0. It was a different game in his day, though, a game won on the ground, not in the air, and Luckman was the perfect player to execute the T-formation, coach George Halas’s offensive set-up, in which the fullback and both halfbacks lined up behind the quarterback.

Halas did not invent the T-formation — he learned it from his coach at the University of Illinois — but in the late 1930s, the Bears were the only team employing it. Other teams used the single wing, lining up the backs on either side of the QB. The T was perfected by Clark Shaughnessy, a Bears adviser who based his innovations on the book Achtung–Panzer!, by German tank commander Heinz Guderian. Like the German blitzkrieg, “Shaughnessy would use wider spacing and men-in-motion to spread the defense, then breach it with quick strikes and misdirection plays, all while concealing the ball as long as possible. The T formation’s sleight-of-hand was controversial, requiring…the right quarterback,” wrote R.D. Rosen in Tough Luck: Sid Luckman, Murder, Inc., and the Rise of the Modern NFL. (Luckman’s father, Meyer Luckman, was a gangster doing time at Sing Sing for murdering his brother-in-law.)

Ironically, considering the offense’s inspiration, the right quarterback turned out to be a Jewish kid from Brooklyn. Halas discovered Luckman playing quarterback at Columbia University, and lured him away from his family’s trucking business with a $5,000 contract — as much as he’d paid Red Grange. Luckman could run, pass, punt, and tackle, and most of all, he had brains. All those qualities made him perfect for running the T, wrote Jeff Davis in Papa Bear: The Life and Legacy of George Halas.

“Physically, he had to possess a ballet dancer’s footwork in designed pivots, step-over, and spins and the ability to throw with accuracy…Since the rules at that time forbade the coach from shuttling in plays, the quarterback in Shaughnessy’s system had to be a ‘field general.’”

Luckman’s first great triumph with the T was the 1940 NFL championship game, in which the Bears defeated the Washington Redskins, 73-0 — the most lopsided victory in league history. Luckman completed only three passes for 88 yards and one touchdown, while the team ran for 381 yards. The next year, when songwriter Al Hoffman composed the team’s fight song, “Bear Down, Chicago Bears,” he included these lines: “We’ll never forget the way you thrilled the nation/ With your T formation.” The thrill was provided by Luckman.

Luckman did go on to set several passing records. In 1943, when he was named the league’s Most Valuable Player, he threw seven touchdowns in a game against the New York Giants, also becoming the first player to throw for 400 yards in a game. His TD record was finally equaled 70 years later by Peyton Manning. That year, he also set the record for most passing yards per attempt, with 10.9.

What makes Luckman the greatest Bears’ quarterback? He won: four NFL championships between 1940 and 1946. An 18-game winning streak, third longest in NFL history. The Bears have never enjoyed as much concentrated success as when Luckman was quarterback. The 1985 Bears may have been the best single-year team in franchise history, but Luckman commanded a dynasty. After retiring, he went on to a successful business career, lending his famous name to Sid Luckman Motors, a car dealership on Ogden Avenue, when the West Side was Jewish.

“You had to see Sid Luckman play in order to believe how good he was,” says former Buffalo Bills coach Marv Levy, who grew up in Chicago as a Bears’ fan. Levy is 98 years old, so he’s one of the few witnesses left.

Granted, it was easier to win championships in those days, when there were only 10 teams in the league. So if Williams wins two Super Bowls, he can be considered Luckman’s peer, but win he must. Good luck, man.