Today WBEZ's Alex Keefe has a good, thorough piece on a subject I've been on about for some time: Illinois's pensions have been underfunded for decades. The problem is bigger in the sense that there are more pensioners (and there will be more in the future), who are living longer and will be more expensive, but in terms of the funding level, it's usually been really low.

Just as a side note to pension funding levels—they're complicated. No one really agrees on what a "healthy" funding ratio (assets versus unfunded liabilities) should be, and the discrepancy is not trivial:

While Morningstar set a 70 percent threshold for fiscally sound systems, and other credit rating agencies peg it at 80 percent, the American Academy of Actuaries went a step further earlier this year, calling the 80 percent funded ratio a “myth.” Plans should aim for accumulating assets of 100 percent of pension obligations, the association said in an issue brief.

Either way, the state's systems are clearly underfunded. But it's an example of how pension systems aren't just math problems, they're also judgement problems. Anyway, here's Keefe:

[T]he state, led by governors and General Assembly members, has never really paid its fair share.

“It’s a matter of never quite putting enough money into the piggy bank,” said Sandor Goldstein, who has been a public pension actuary in Illinois for more than three decades.

You can think of an actuary as an accountant with a crystal ball: They use statistics to try and project how much stuff is going to cost ten, twenty, thirty years down the road – stuff like retirement benefits.

But in Illinois, the state’s pension contributions are discretionary, so governors and lawmakers can basically contribute whatever they feel like. And lawmakers have been ignoring guys like Goldstein for decades.

“I have some reports from these pension commissions that complain about the underfunding back as early as 1945,” he said, before plucking a shopworn paperback report from the shelf of his downtown Chicago office.

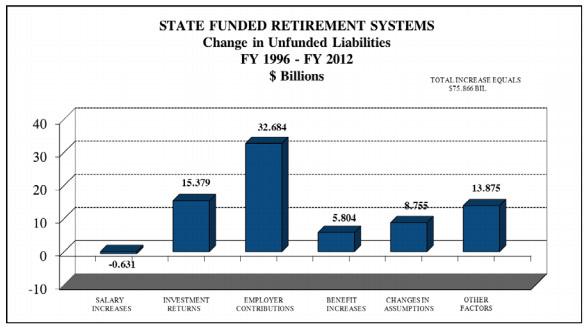

Yep. It's been a problem for most of their existence. And it's been a problem recently, too. The state's Commission on Government Forecasting and Accountability (aka COGFA) did an analysis of what factors have caused underfunding for FY 2012 and 1996-2012. The biggest cause? "Employer contributions," i.e. not putting enough money in the piggy bank. Way more than benefits; way more than negative investment returns (PDF).

This year state underfunding was outpaced by "changes in assumptions," which refers to the Teachers' Retirement System deciding that eight percent returns are more realistic than 8.5 percent. That means TRS expects its assets will make less money, which increases the unfunded liabilities, which are ultimately future projections. (This is how judgements effect what looks like a scarily concrete number.) Here's the portrait from 1996-2012:

During that time, $75.7 billion was added to pension IOUs. 43 percent of that was due to shortfalls in employer contributions.

Also, note this: "But in Illinois, the state’s pension contributions are discretionary, so governors and lawmakers can basically contribute whatever they feel like. And lawmakers have been ignoring guys like Goldstein for decades."

It's not just that they're discretionary by habit, or because of politics. They're allowed to be discretionary by constitutional law. In the 1990s, representatives of the state's retirement systems filed a complaint that argued the state was totally screwing its employees ("impairment," to use the legal term) by underfunding its pension systems, because eventually the money wouldn't be there if the state kept underfunding the systems (PDF):

The plaintiffs’ alleged that the state failed to comply with the funding provisions contained in Public Act 86-273 (eff. Aug. 23, 1989), which required the state to contribute additional incremental amounts each year, when, combined with employee contributions and investment returns, would meet the annual normal cost for each fund in seven years, as well as amortize the unfunded liability for each pension fund over a 40-year period.

That act was replaced by the pension "ramp" Keefe's piece discusses. And the court told them, sorry: the state has to pay you, but the state doesn't have to fund the systems that pay you unless it's on the brink of disaster:

The court examined the defendants’ claims that the pension protection clause creates an enforceable contractual right only to receive benefits, not to control funding. The court concluded that the plaintiffs’ allegations of inadequate funding on the part of the State were insufficient to constitute an impairment of benefits in violation of article XIII, section 5 of the Illinois Constitution. The plaintiffs could not prove that the funds at issue were “on the verge of default or imminent bankruptcy” or that the benefits were in immediate danger of being diminished (182 Ill.2d at 233).

In other words: it might look like the state's going to be unable to pay you at some point down the line. Get back to us when it's clear it can't.

The court found that the framers of the Illinois Constitution were careful to craft in the pension protection clause an amendment that would create a contractual right to benefits, while not freezing the politically sensitive area of pension financing.

That language is directly from the decision: "freezing the politically sensitive area of pension financing." The pensions themselves are guaranteed, but we have to rely on politicians for the politically sensitive area of pension financing, at least until it's almost too late.