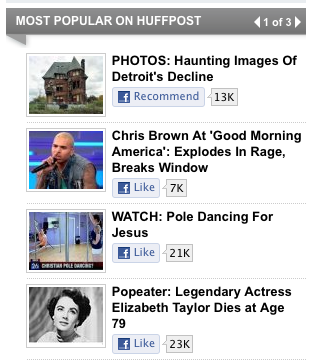

One of these things is not like the other things:

The pictures in question are from The Ruins of Detroit, a lavish book by 20-something photographers Yves Marchand and Romain Meffre. They’ve been making the rounds, from Juxtapoz to Apartment Therapy to The Coolist to Time. Noreen Malone, in a thoughtful essay for The New Republic, says that "we have begun to think of Detroit as a still life":

"I suspect it’s not an accident that the pictures of Detroit that tend to go viral on the Web are the ones utterly devoid of people. We know intellectually that people live in Detroit (even if far fewer than before), but these pictures make us feel like they don’t…. Without people in them, these pictures don’t demand as much of the viewer, exacting from her engagement only on a purely aesthetic level. You can revel in the sublimity of destruction, of abandonment, of the march of change—all without uncomfortably connecting them with their human consequences.

I don’t necessarily think she’s wrong, but I’m not sure that’s the whole story, either. "Disaster porn," as the phrase has it, can be perfectly popular (and perfectly exploitative) with people in it, as Maura O’Connor and David Sirota noted about coverage of the Haiti earthquake; their complaint was that the coverage elided not people, but politics.

While reading up on disaster porn, I came across an intriguing explanation:

In the recent (and excellent) documentary Los Angeles Plays Itself, the director and film scholar Thom Andersen makes the argument that disaster movies tend to appear at moments when a culture is in crisis about the legitimacy of authority (hence the burgeoning of the genre in the post-Watergate years).

It’s a more specific version of an argument I find convincing: the particular nature of our disaster and horror obsessions reflect specific cultural anxieties, as Peter Wynn Kirby and Andrew O’Heir have observed recently about Japan’s nuclear-disaster-saturated popular culture.

And I think the virality of Detroit ruin porn is very much related to American anxieties. There’s the collapse of the economy, in which the disaster scenario of nine-percent unemployment is considered the new normal; the "Europeanization" of cities, in which a ring of poverty is sandwiched between a urban core and the suburbs; the ongoing foreclosure crisis; tensions between unions and government in Rust Belt/Great Lakes states; the fear that America’s wealthiest have no incentive to invest in the country.

Photographers and reporters have gotten ripped for misrepresenting Detroit’s decline–presenting a fiction of a city without people. But the exodus from Detroit is quite real:

It was the largest percentage drop in history for any American city with more than 100,000 residents, apart from the unique situation of New Orleans, where the population dropped by 29 percent after Hurricane Katrina in 2005, said Andrew A. Beveridge, a sociologist at Queens College.

The number of people who vanished from Detroit — 237,500 — was bigger than the 140,000 who left New Orleans.

Over the past month or two our neighbors in Wisconsin, Indiana, and Michigan have been at the center of American domestic politics. It feels like the Midwest is trying to save itself, and like a turning point for the disappearing middle class. It’s an anxious time to live here, and anxiety will often express itself through the exaggerations of fiction. The barren Detroit of a thousand disaster-porn slideshows isn’t real, but the fear that’s turning them into linkbait is.

Recommended reading: Detroitblog, drawn from the Metro Times and features journalism deserving of much more attention than it gets; The Origins of the Urban Crisis, Thomas Sugrue.