There is no better way to see Chicago than on a Divvy e-bike. That little boost from the pedals feels like a superpower, the same mechanical augmentation of muscle that the $6 Million Man received from his bionic limbs. If I was going to ride the full 23-and-a-half miles of Western Avenue, Chicago’s longest street, I needed that extra energy. I had a more practical motivation, too: whenever I ride my $399 Reid Comfort bike in a far-flung part of town, it gets a flat tire. It’s happened in Bronzeville, in East Garfield Park, in South Deering. Now I only use it for trips to the post office, the barbershop, church, and my Scrabble club. If a Divvy gets a flat, you can abandon it by the side of the road and pick up a fresh one, like the Pony Express did with its horses. E-bikes cost money, but so do inner tubes.

I unlocked an e-bike at Western and Howard, an intersection surrounded by remote, forlorn, unglamorous strip malls with empty parking lots. Across the street were a Dunkin’, a Dollar Tree, and a Tide Laundromat. This corner was representative of Western Avenue’s personality. Although it’s known as a street that “provides a look at Chicago’s many personalities” and “a varied collection of immigrant and ethnic communities,” for most of its run from West Ridge to Morgan Park, Western is a practical thoroughfare of brick warehouses, gas stations and car dealerships. I was going to see a lot of cars for sale on this ride.

Western got its name because, from 1851 to 1869, it was the western border of Chicago. At another time, perhaps 20 years ago, it was the boundary between modern lakefront Chicago and the city’s traditional neighborhoods, although gentrification has pushed that dividing line west, to Kedzie at least.

The Pakistanis are Western’s first immigrant community. At the corner of Albion is Taxi Town, a lot crowded with green cabs. Cab driving has always been popular with entrepreneurial immigrants; it’s especially popular with Muslims, because it gives them the freedom to stop for five daily prayers. Devon Bank, that mod building at 6445 N. Western, advertises Islamic financing. Just south of that is a shop that kills live poultry according to “100% Zabihah Halal” standards.

According to the Tribune, Western is “the car capital of the city and state…because of its convenience to all areas of the city and many suburbs.” There are 70 dealers on the avenue, but the most famous is gone. That was Z Frank, at Peterson, once the world’s largest Chevy dealership. Its jazzy, monumental sign may have been second only to the Magikist lips in the city’s neon pantheon. The founder’s son was a Sierra Club activist who promoted environmentally friendly cars. Perhaps he was too successful: Z Frank closed in 2008, replaced by a Toyota dealership.

South of Peterson are the West Ridge Nature Park and Rosehill Cemetery, Chicago’s biggest graveyard, final resting place of Vice President Charles Gates Dawes, weiner pioneer Oscar Mayer, and thousands of Civil War soldiers. In Lincoln Square is the DANK Haus German American Cultural Center, remnant of an older immigrant community. Western isn’t the main drag of Lincoln Square, though. Or North Center, Lincoln Park, Bucktown, or Ukrainian Village. It’s more a back lot, mile after mile of law firms, taverns, driving schools and insurance agencies, and brand-new brick apartment blocks named The Western and The Connacht. Here, it’s the city’s spine, rather than its heart. Margie’s Candies, at the six-way intersection with Milwaukee and Armitage, is the next notable landmark.

Western Avenue’s halfway point is somewhere around Cermak Road. So somewhere around there, on a desolate stretch criss-crossed by railroad tracks, somewhere between Pilsen and Little Village, I stopped for French toast and orange juice at Don’s Grill, a roadside diner with a dozen stools, and signs in the window advertising “Biscuits & Gravy” and “Rib-eye Steak ‘n Eggs with Pancakes.”

Just south of the Sanitary and Ship Canal, which it crosses as an Art Deco-inspired bridge, Western splits in two. Western Avenue does its usual commercial business — car wash, muffler shop, Oil Express — but Western Boulevard is a shady street with a grassy median and a nice collection of greystones. It bypasses McKinley Park, site of languid Sunday softball games.

The Westerns reunite at the Gage Park Fieldhouse, which looks like an Oriental temple designed by Frank Lloyd Wright and cast in poured concrete. Now, the street is five lanes wide, and it’s a used-car salesman’s heaven — if it’s possible for such a place to exist. This stretch of Western has more worn-out automobiles waiting to go home than the city auto pound. Easy Finance Auto Group. Mr.Kars. Magic Auto Sales. Rainbow Auto Mart. Rows and rows of Chevys and Fords stickered with low, low prices. An ’07 Saturn for $4,999. A ’10 Fusion for $4,900. Quality Cars. Used Cars. Stop Save Now. Guaranteed Approval. Bad Credit? No Credit? Drive Home Today! It was Sunday, though, so all the lots were closed, thanks to a law passed at the insistence of auto salesmen who wanted to be able to take a day off without losing a customer to their cutthroat competitors.

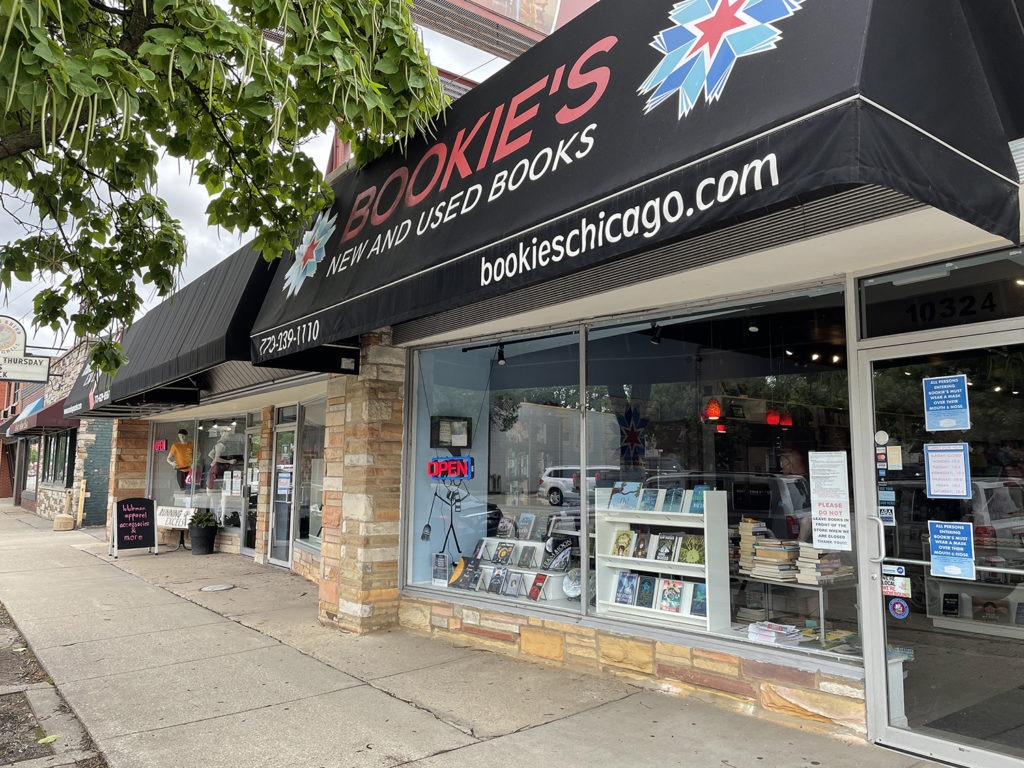

Beverly is the only neighborhood where Western is the high street. You can see that Western Avenue is really starting to make something of itself when you pass the Original Rainbow Cone, at 92nd Street. Then there’s Janson’s Drive-In Hamburgers, whose neon sign slowed your grandpa’s ’60 Impala. Bookie’s New and Used Books. Horse Thief Hollow, a gastropub with its own brewery. My bike’s battery went dead at 111th Street. I docked it in front of McNally’s, an Irish pub with a tattered “Back the Blue” American flag drooping over the door. McNally’s looked like the most Beverly joint ever, so I went inside for a beer. After 23 miles, with one left to go, I was thirsty. Behind the bar was a framed photo of Ella French, the Chicago police officer killed in the line of duty last August. Taped to the wall were paper badges bearing the names of donors to the Chicago Police Memorial Foundation. A banner advertised a raffle to benefit St. Cajetan, the Catholic church around the corner. I was served a Bud in a Goose Island glass with a Sox logo. All around me, gray-haired men discussed the “gawf” on television. There was an academic study on the decline of the Chicago accent in Beverly, but it can still be heard among the gray-haired patrons of McNally’s, who greet every regular by name, and know where his daughter went to high school.

I pulled out a charged-up bike for the final mile. Across 119th Street, I saw this sign: “Welcome to Historic Blue Island. Established 1835.” Blue Island is neither blue, nor an island. Beer is sold there on Sundays, and it’s not separated from Chicago by water. I had hoped for a celebratory lunch here at the finish line, but McDonald’s is the only restaurant on the corner. I backtracked to Beverly. In the parking lot between McNally’s and the Beverly Arts Center, the members of the Chicago Gay Men’s Chorus were skylarking before their afternoon performance. You really can see all of Chicago on Western Avenue, even in places you never expected to see it.