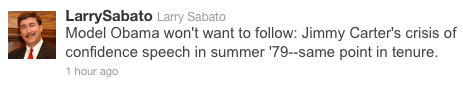

So this was eerie:

I may have a mind-meld with Larry Sabato from having grown up in Virginia and watching the news a lot. He’s basically Virginia’s Dick Simpson: inescapable during election season since before you were born (one of my favorite blog titles is "Not Larry Sabato," which is funny if you’re from where I’m from). So it was weird to see him tweeting the exact same thought I had on the bus this morning, which was inspired by a couple things.

First: I’ve been reading up on income inequality recently, as you might have noticed. This led me to Jefferson Cowie’s Stayin’ Alive: The 1970s and the Last Days of the Working Class, an economic and labor history of the decade. In the chapter "The New Deal that Never Happened," about labor’s failed attempt at pushing labor-law and full-employment legal reforms on the Carter administration, this paragraph jumped out at me:

First: I’ve been reading up on income inequality recently, as you might have noticed. This led me to Jefferson Cowie’s Stayin’ Alive: The 1970s and the Last Days of the Working Class, an economic and labor history of the decade. In the chapter "The New Deal that Never Happened," about labor’s failed attempt at pushing labor-law and full-employment legal reforms on the Carter administration, this paragraph jumped out at me:

By the end of the decade, the Carter administration teetered on the brink of failure, but the problems he faced were nearly intractable. Carter "needed to deal at the same time with a catalogue of competing and inherently contradictory claims on government in his administration," explains one biographer: "to promote employment while halting inflation; to reduce taxes while meeting pressing social needs; to maintain business confidence without alienating traditional Democrats; and to stabilize the dollar abroad without undercutting his economic program at home. As Stuart Eizenstat explained, the president’s contradictory and confusing goals made it worse. "One always new that [Carter] wanted to spend as little money as possible, and yet at the same time he wanted welfare reform, he wanted national health insurance, he wanted job training programs." Lacking both the willingness to chart a bold new course and the political winds to drive innovative policy (speechwriter James Fallows dubbed it the "passionless presidency"), Carter emerged as a new brand of conservative Democrat of the type that would go on to dominate the party, tempered by a personal disposition ill-suited to the structural crisis he faced. As a result, what some hoped would be a New Deal revival ended up as the "last hurrah" of the New Deal faithful. (p. 266)

Maybe not quite the last hurrah—there was a bit of hope for a New Deal revival from the faithful early in Obama’s administration, as you can see, or at least from the kids of the New Deal faithful. Cowie himself tossed some water this phenomenon in a recent essay.

Second: the Federal Reserve’s decision to let its economic rescue program peter out and let the "moderate" recovery continue under current conditions, despite continued unemployment hovering around nine percent—a point higher than the administration expected, without the modest stimulus package, two years ago.

Second point five: Barry Ritholtz of The Big Picture did a Wordle word-map of Ben Bernanke’s recent Q&A, and the word being thrown around the most was "inflation," which would have made more sense in the late 1970s.

Third: The centrality of the federal deficit to the current economic debate. The Obama administration’s less than hard line has gotten it accused of blundering and "flunking bargaining 101." But Kevin Drum pulls out Occam’s Razor:

There’s just no way that Obama and Reid and the rest of the Democratic brain trust were literally so stupid that they didn’t understand this. A far more parsimonious explanation is that this is roughly what Obama wanted. He wanted spending cuts, but he wanted Republicans to be the ones to take the lead. And that’s what happened.

Returning to Cowie:

Much of the inflated liberal hopes about what was possible in the 1970s were informed by an unconscious and misguided New Deal triumphalism that allowed the surface glimmers of a Carter presidency to appear like something more substantial. As a new kind of Democrat, Carter ran and governed more in the mode of the Progressive Era good government steward—"attempting to make the government more competent and administratively more rational" rather than the anti-Washington populist crusader he sometimes ran as or the incipient New Dealer many hoped he might become. (p. 265)

Reading Stayin’ Alive, I couldn’t help but be grateful—thanks, Mom and Dad, for having me later than you might have—that I missed out on the 70s by six months. Reading further, I couldn’t help but think that I’d spoken too soon.