Photograph: juggernautco (CC by 2.0)

This is starting to look like the summer of the "flash mob." It started with the closure of North Avenue Beach due to several cases of heat exhaustion. But rumors, which could initially be found at the Second City Cop blog—update: here's the right link, that one's from 2010—and newspaper comment threads, spread that the closure was due to groups of young people and/or flash mobs, i.e. groups assembled by text message or social networks to cause havoc (or, in more innocent cases, levity).

The CPD denies that was behind the beach closure, but flash mobs continue to dominate the news: last weekend, it was five youths arrested for robberies in Streeterville and on the Mag Mile, and last night another robbery downtown, though it's unclear whether there was any flash to the mob or whether it was just standard-issue street violence.

It's not terribly surprising that this incipient panic would begin on the beach. Chicago has a long history of newsworthy beach violence, which actually used to be much worse. In the early 20th century, beach riots were a fairly regular occurrence; from a scan of the Tribune archives, it seems residents could count on one every summer or two during the 'teens and 1920s, perhaps because they were even more heavily used before the advent of air conditioning. Beyond the infamous 1919 race riots, which started on a beach at 29th Street and lasted for eight days, Chicago's free and clear lakefront was often the scene of territorial battles and random violence.

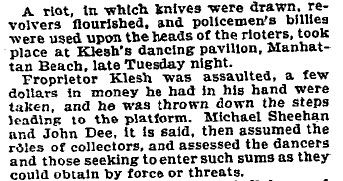

1898:

(Manhattan Beach was "a popular spot for middle-class boys and girls to meet in the early decades of the twentieth century." It would later become Rainbow Beach, and would be the site of another riot.)

1916:

(Allegedly Connell was not wearing a suit that distinguished him as swimming "under the jurisdiction of the Wilson beach company.")

1916:

(On the same day, there was a crush at the Clarendon beach when 300 people tried to force their way to the water; one man was slightly injured, "and about twenty men and women fainted in the locker rooms." Temperatures were hot that summer; one night in July an estimated eight to ten thousand people slept in Grant Park, according to the Tribune.)

1917:

("Those in the crowd accused the police of undue violence, of striking girls in bathing costumes, and of roughly handling little children.")

1919:

(The beginning of one of the most notorious race riots in American history; it lasted eight days, and 38 people were killed.)

1921:

(The "simple little remark" was an exchange: upon hearing two lifeguards say "something about Jews, which Mrs. Stein resented," she responded to the [white] lifeguards, "I hear a life guard once married a white girl." According to R.L. Bessmer, one of said lifeguards, he had said nothing about Jews, and "believed he had been called a Negro and he resented it. He is not a Negro, but his skin has been tanned such a dark color that he has become sensitive about his complexion.")

1929:

(The above is an editorial, which requests: "Under the circumstances it would seem that the Negroes could make a definite contribution to good race relationships by remaining away from the beaches where their presence is resented.")

1961:

("Police claimed they foiled a plot by gangs of youths from various neighborhoods on the city's south and west sides to attack the integration waders at the sound of a bugle." Social media, circa 1961.)

1962:

(The scarlet head-shaving: "Judge Obermiller said yesterday he ordered the boys' heads shaved to identify them as 'teen-agers who drink.'" Because in 1962, the way to identify miscreants was… a buzz cut.)

1985:

("Local residents, however, said the increased presence of groups of high-school-age youths in the area concerns them.")

Also worth noting: the ostensible cause of the July 1966 riots, or at least the catalyst, was the closing of fire hydrants that residents were opening to cool off. In the wake of the riots, the city installed pools near where the violence occurred:

I'm also reminded of Robert Caro's The Power Broker, his magisterial biography of urban planner Robert Moses, some of which is devoted to the racial conflicts that arose over access to New York's beaches and pools:

Whites routinely beat up blacks and Puerto Ricans in East Harlem when they tried to swim at Jefferson Pool; on occasion whites swam at Colonial Pool, although others felt unwelcome. Moses knew about these situations, referred to in his Harvard speech. Clearly he recognized racial and ethnic categories were in flux in the 1930s: the line was hardening between black and white, as the city became more racially diverse, complicated place. ["Race, Space, and Play: Robert Moses and the WPA Swimming Pools in New York City," Marta Gutman, Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, December 2008]