The Civic Federation continues to sound the alarm on local pension costs, this time analyzing the status of the city's pensions after the end of fiscal year 2010. It's about as bad as you've probably come to expect:

In percentage terms, Chicago's plan for municipal employees received the lowest amount of required contributions in 2010. The city put in just 32 percent of what was needed to cover benefits. With more than $6 billion in unfunded liabilities, the municipal pension plan also has the largest debt load of any Chicago-area fund.

The Chicago Teachers' Pension Fund received the highest percentage of required contributions in 2010. The fund received 81.7 percent of the money it needed that year, about $290 million. Projected budget shortfalls for 2011, however, led CPS to seek a partial pension holiday from the General Assembly, which drastically reduced the amount the district was required to pay into the fund during the next three years.

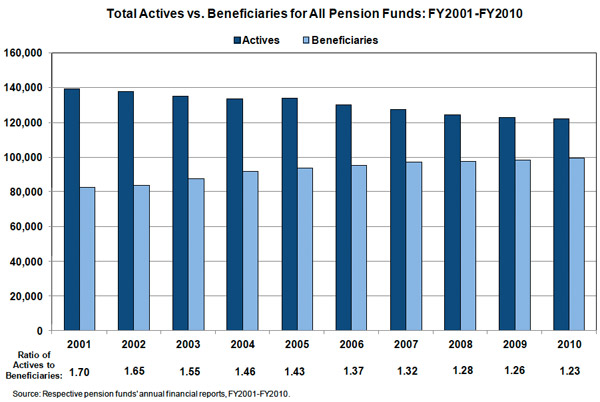

But the thing that surprised me the most from the report, released today, wasn't the typically substantial difference between the actuarially required contribution and the actual contribution, which tends to be high—the ARC is large, and the city doesn't have much money to spare. It's the change in ratio between active workers and retirees.

That's a significant drop. And the big driver has been teachers.

Teachers make up the largest number of beneficiaries out of all the pension funds: 24,600, about 1,000 more than the municipal laborers' fund. In 2001, there were 2.18 active teachers for every retired, pension-receiving teacher. In 2010, the ratio was 1.38 to one. The laborers' ratio declined from 0.96 to 0.65—which would be worrisome, but it's a small fund, and reasonably well funded. At 73.8 percent, it's in better shape than any other fund, and in a reasonably safe zone.

On the other hand, the teachers' fund is by far the largest, about a third of all pensions by asset. And it's declined from 100 percent funded in 2001 to 67.1 percent funded in 2010—and that, after a 14-percent rate of return in 2010, offsetting some of the 22-percent loss in 2009 and bringing it even for the past few years. Some of what's driven that decline is teacher retirements. A lower teacher-to-retiree ratio means more people drawing pensions and fewer paying into the system, forcing up the actuarially required contribution, the shortfall, or both.

And a huge wave is likely to come: "So far 1,954 Chicago teachers plan to retire. The Chicago Teachers Pension Fund estimates that number will hit 2,000 before summer ends. That would be a 40 percent jump over last year." Between fiscal years 2009-2010, the ratio of teachers to retirees actually improved after a decade of decline; it's likely to go up again.

It highlights the tremendous difficulties of addressing pension-fund shortfalls. Cutting pensions is likely to move teachers into retirement, further reducing the ratio of teachers to retirees and increasing the amount the city has to pay into the retirement system. It also reduces the ratio of how much teaching the city gets for its money versus how much past performance it's paying for—headcount is reduced and it puts future pension budgeting on more stable ground, but it creates a lot of difficult choices in the present.

Photograph: fcstpauligab (CC by 2.0)