The Soviet launch of Sputnik didn't just touch off an arms race—it touched off an educational race, as America responded not just to a perceived missile gap, but an academic gap. Life, bastion of the country's conventional wisdom, sounded the alarm; Sloan Wilson, fresh off the success of The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit, shouted "fire" in a crowded classroom (emphasis mine):

In their eagerness to be all things to all children, schools have gone wild with elective courses. They build up the bodies with in-school lunches and let the minds shift for themselves.

Where there are young minds of great promise, there are rarely the means to advance them. The nation's stupid children get far better care than the bright. The geniuses of the next decades are even now being allowed to slip back into mediocrity.

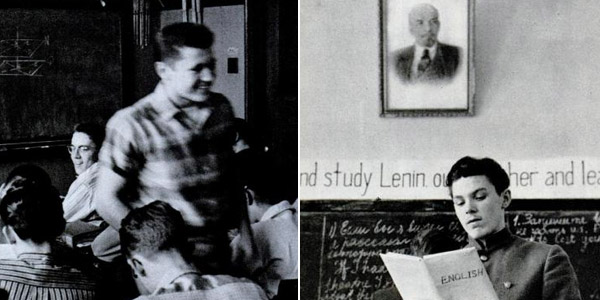

Ground central was Chicago's Austin High, where Stephen Lapekas "starts out almost every day by meeting his steady, Penny Donahue." When he gets there, "classes at Austin are relaxed and enlivened by banter."

Sounds great, right? A steady girl, some enlivening banter? It would, to a lazy American.

For Stephen, who is taking an academic course, this year's subjects include English, American history, geometry and biology, respectable enough courses but on a much less advanced level than Alexei's. The intellectual application expected of him is moderate. In English, for instance, students seldom bother to read assigned books and sometimes make book reports based on comic book condensations. Stephen's extracurricular activities, in which he really shows talent and energy, leave him little time for hard study. He is the high school's star swimmer and a leader in student affairs. As a result, though the teachers consider him intelligent, he is behind in math and his grades are mediocre. "I worry about 'em," he admits, but that's about as far as it goes.

Who's Alexei? He's a 16-year-old Moscovite, the son of a hard-working taiga mom, whose superior educational system will place him far ahead of the lackadasical Lapekas. Life's photographer caught Lapekas laughing along with his class at his incompetence in geometry, while Alexei was earnestly studying the moral decay of Stephen's hometown (that's Sister Carrie he's reading).

Maybe Wilson had a point; 40-some years later, I could barely get through turn-of-the-century American realism myself. Because it was boring? No:

Obviously it his impossible to make sweeping pronoucements on the industry or intelligence of some 34 million schoolchildren and more than a million teachers. Some of the criticism is the inevitable blowing off of steam which always accompanies a democracy's efforts towards self-improvement. Still the statistics cannot be disputed and it would be difficult to deny that few diplomas stand for a fixed level of accomplishment, or that great numbers of students fail to pursue their studies with vigor. Studies show that brilliant children in this country are nowhere near as advanced in the sciences as their opposite numbers in Europe or Russia. Why?

Stop me if you've heard this one before—say, in the New Yorker this week. It's those anxious yet tolerant parents:

A junior high school teacher recently wrote that students nowadays "are being smothered with anxious concern, softened with lack of exercise, seduced with luxuries, then flung into the morass of excessive sex interest…. They are overfed and underworked. They have too much leisure and too little discipline."

And the unfortunate prospect that a dropout could have anything other than a joyless road to mortality:

In Russia and Western Europe children had more reason to study. In the Soviet Union, especially, scientists and technicians were the new aristocrats, and the only way to join their ranks was through academic accomplishment. Today if a Russian boy fails in school he may face the bleak prospect of being a day laborer or serving in some other lowly capacity. No one in Russia can entertain the dream of leaving school early and making a million rubles as a salesman.

I didn't read Crime and Punishment as a cautionary tale of what happens when you drop out of school, but then again I missed almost the entire Cold War. Which was, ultimately, at the heart of the panic: "space ships and intercontinental missiles are not invented by self-educated men in home workshops." Now it's iPhones and financial instruments, but the moral of the story is essentially the same. So when Elizabeth Kolbert writes that our spoiled children are "a social experiment on a grand scale, and a growing number of adults fear that it isn’t working out so well," I can't help but wonder if those parents remember how softbatch the Greatest Generation thought they were, and how their happy apathy was going to get us all incinerated.