Via Greg Hinz, Roosevelt prof Stephanie Farmer just released a report breaking down what schools in Chicago have received tax-increment finance funding, how much, what students they serve, and where they're located. It's an interesting read, and significant because it addresses one of the biggest controversies of the TIF program.

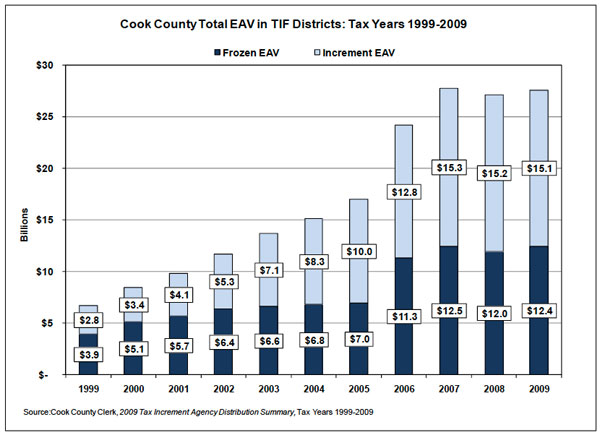

One of the accusations lobbed at TIFs is that they divert money from public schools—or, alternately, they cause tax levies to increase in order to replace money that would otherwise go to public schools. A quick reminder: TIF designation fixes the amount of property tax revenues that go to the usual places for up to 24 years. That "additional" money, the increment, then gets plowed back into the district to finance economic development. The theory is that the district gets the property tax revenue it would have gotten anyway; the reality is much trickier, because of obvious things like inflation, broader socioeconomic trends, and so forth. Either way, the many, many TIFs that have sprouted up since Harold Washington plunked one down in the Loop a couple decades ago have taken up an increasing percentage of city revenues. Here's your periodic reminder:

So. One of the ongoing defenses of TIFs in regard to its effect on school funding is that TIF money is spent building schools, as Ben Joravsky described six years ago. At the time, Mayor Daley promised one billion dollars in TIF spending over six years to build schools. Farmer's report finds that 28 schools have received $857.8 million, and another 26 schools have used over $32 million TIF money to meet ADA accessibility standards. (Another question is whether TIF money should be spent on schools, but that's a big question.) And she breaks down where that money has gone.

The most interesting and/or significant finding is this: "Though selective enrollment schools account for 1% of all CPS schools, they received 24% of all TIF funds spent on school construction projects," or $209 million dollars. By comparison, open-enrollment neighborhood schools, making up 69 percent of CPS schools, received $415 million, or 48 percent. Farmer explains:

The city’s nine selective enrollment schools were created by Mayor Richard Daley to help retain middle-class families who he believed would leave CPS and the city in pursuit of what they perceive as better schools in the suburbs.

Expect more where those came from, Jean-Claude Brizard told Linda Lutton in April.

This feeds back into the question of whether TIF money should be spent on schools. One of the points Ben Joravsky has made over the years is that there's been a TIF mission creep from strict economic development to funding basic infrastructure, such as school-building, as well as a shift from repairing blighted neighborhoods to attracting businesses to the central business district. Joravsky and Mick Dumke found with a ward-by-ward breakdown of TIF spending from 2004-2008 that 43 percent of TIF money was spent in the three wards in and around downtown.

But that's the funny thing about Farmer's findings: selective-enrollment schools are intended as economic development, so it's really not a surprise that so much TIF money has gone into them versus open-enrollment schools. Intended to address blight, TIFs have been shifted to block flight, and Farmer's work shows how the dilemma is mirrored with the use of TIF money to fund education.

Photograph: naosuke ii (CC by 2.0)