Today’s the last day of school ever at 28 Chicago Public Schools (the Sun-Times is liveblogging it), victim to a frequently reported $1 billion budget gap.

Closing the schools won’t address the budget gap next year, since there are substantial upfront costs, and CPS has said it’s close to covering the gap this year (though not, obviously, in any sort of structural way). So they’re estimates, and sometimes those estimates have not come to pass. Meanwhile, DNAinfo reporters have been on the tail of school-level budget cuts.

So take the numbers with a grain of salt. But it’s still worth asking: Where did this deficit come from?

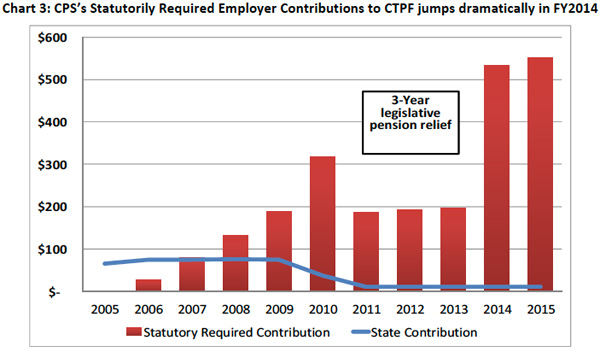

Well, a lot of it’s been there all along. It’s just that CPS now has to start paying it off. And it represents a big, big chunk of that estimated billion dollars. From the CPS 2013 budget:

What happened? In 1995, CPS was facing a projected 1999 deficit of $1.4 billion, plus the familiar problems of low scores and dropout rates. So Paul Vallas proposed a fix:

Vallas, who will submit his proposed $2.9 billion budget to the Chicago School Reform Board of Trustees Monday, said he trimmed $161.8 million by reducing 1,700 central office staffers and trades workers; eliminating waste from special education and other departments; and gutting an elaborate program designed to network the district’s computers.

At the same time, he came up with $206.8 million in revenue by contributing less to the teachers pension fund; keeping some of the discretionary funds schools get for low-income students; putting 20 surplus properties up for sale; and shifting to the general fund monies that financed after-school programs at school fieldhouses.

So CPS was able to reduce its pension funding; they were supposed to pay in $93 million, but cut that to $10 million. Meanwhile:

Part of the deal was that property taxes that had been directed to pensions would instead go directly into school operations. Another part of the deal was that the General Assembly would make it a “goal and intention” each year to give the city teachers pension fund 20 percent to 30 percent of the amount allocated for the suburban/downstate teachers pension fund.

As Eric Zorn points out, the general assembly met its “goal and intention” exactly one year, 1995, when it contributed 23 percent. (They did manage to keep it in double digits up until 2000.) That was supposed to balance out the CPS’s pension holiday, which lasted a decade, but it fell precipitously. That’s the blue line above.

CPS got a break on paying into the pension fund, and the state slacked off on it. But everything stayed cool—i.e. the funding ratio stayed above 90 percent—because of investment returns. Then the stock market cooled off and the ratio started falling. From 2002-2011, the number of retirees increased by about 7,000, and the number of contributing members fell by about the same. In 2004 the funding ratio dropped below 90 percent. Which became a problem in 2006, wrote Jason Grotto in 2010:

In 2004, it dipped below 90 percent for the first time, but because funding is based on results from two years earlier, that milestone didn’t affect the district until 2006. That year the school system had to contribute $36 million to the pension fund. The bill nearly tripled to $90 million in 2007, and by this year it was $340 million — an 844 percent increase in just four years.

So that’s why the red bars start going up in 2006, climbing until you get to 2010. And then, Grotto continues:

Among the “reforms” inserted into Illinois’ 1,400-page pension code was a three-paragraph clause that reduced CPS contributions, giving it a pass on more than $1.2 billion during the next three years.

The move will save the school district money in the short term, but once the holiday is over, reality will set in again.

You may recall that something else happened between 2006 and 2010: the bottom fell out of the economy. In 2008, the fund’s rate of return was -5.3 percent; in 2009, it was -22.4 percent. From 2002-2011, covering the end of one recession and the whole of another, the fund’s compound rate of return was 5.7 percent; the assumed actuarial rate of return is eight percent.

It’s a problem that built slowly, then snowballed: CPS’s pension holiday combined with falling revenues from the state; the impact of two recessions, one enormous; a changing ratio of beneficiaries to active members; and a second pension holiday that gave CPS a reprieve during the depths of the recession but added to its burden coming out of it. And as it starts to climb out of the hole, CPS is paying off past attempts to climb out of past holes.