We'll take all this money from sin

Build big universities to study in

Sing "Amazing Grace" all the way to the Swiss bank

—Bob Dylan, "Foot of Pride"

At Crain's, Greg Hinz addresses something I've written a fair amount about: the city's increasing reliance on fees and fines, in particular red light cameras and cigarette taxes. He brings up an important point about how they're regressive, and gets pushback from Laurence Msall:

Laurence Msall, president of government watchdog group the Civic Federation, disputes my theory that fines are more regressive than taxes, thereby hitting minorities more than whites. He likens fines to user fees, which he says are fairer than broad-based taxes.

The cigarette tax has been held out as one that will disproportionately impact the poor. And rates of tobacco use are definitely higher in poorer communities in the city:

Smoking prevalence varied from 18% in the wealthiest (predominately White) community to 39% in the poorest (predominately Black) community. In a contiguous pair of communities, one Mexican and the other Black, smoking prevalence varied by a factor of 2. Men, residents in poorer households and households without telephones, and residents with less education were most likely to smoke.

The line of argument goes like this: tobacco is addictive; therefore not everyone will quit; therefore higher taxes will impact the poorest communities the most. But the poor are also very attentive to taxes—more attentive to some forms of tax than the rich. And if you push the argument far enough, it suggests ways to make taxation less regressive.

This comes from Scarcity: Why Having Too Little Means So Much, a new book by Harvard economist Sendhil Mullainathan and Princeton psychologist Eldar Shafir. As their professions suggest, it's a multidiscplinary look at how resource scarcity—time, money, food—changes how people behave and even how the brain functions.

Mullainathan and Shafir present evidence that the poor, at least in a short timeframe, are more rational economic actors than the well-off, at least from an economist's perspective. For instance: when surveyed, both the rich and poor say they would drive out of their way to save $35 on a DVD player, but the poor are much more likely to drive out of their way to save $35 on a $1,000 laptop. Which is actually more rational, from an economic perspective: the extra drive is worth the same amount of savings, whether or not it's a small savings by percent of the total cost.

The poor are more likely to be able to accurately tell you the price of small groceries; they're more likely to see through retail tricks to find the lowest per-unit price. "The poor, in short, are expert in the value of a dollar," the authors write. (By other measures and timeframes they are less rational, but that's a subject for the book, not for me.)

And this comes to bear on cigarette taxes, and other forms of potentially regressive flat taxes:

Knowing prices often involves more than just reading the label. It requires vigilance since what you see is often not what you pay. Cigarette taxes, for example, come in two varities. The excise tax shows up in the posted price, but the sales tax does not; it is added at the register. If you look at just the posted price, you will miss the sales tax. When exise taxes—the visible price—change, rich and poor smokers respond. Both smoke less. Not so for a change in the sales tax—the hidden price. Only low-income consumers respond to that. Only the low-income weigh sales and excise taxes equally (as they ought to). They not only notice prices; they are better at deciphering that the total price is more than the one posted.

Chicago's cigarette tax is an excise tax, not a sales tax, so it's included in the posted price. But the paper the authors are referencing here suggests an interesting policy conclusion: to make taxes on specific things less regressive, hide the tax. For obvious reasons, cigarettes are probably not a good subject for this, but it presents an intriguing option for more harmless products.

Sin taxes strike a balance: they are mechanisms designed to keep people from doing something (or at least doing less of it), while profiting from the reality that people will continue to do that thing. And that's one of the dilemmas that Hinz addresses—it's great if the cigarette tax stops people from smoking, but then the city loses a revenue stream. It's also great if the city has a revenue increase if they don't stop, but then people aren't smoking less, and the taxes fall disproportionately on the people who can't afford it.

But in theory, the tax strikes a balance. The poor are more likely to smoke, and will have less money if they don't quit, but stand to benefit more if they do. It doesn't obviate the dilemma, but it at least gives a sense of the dynamics, and what the effects are likely to be.

There's a parallel here with red-light tickets. The poor are more likely to be killed by cars. (This holds up not just in the U.S. but in other countries as well, though no one's exactly sure why—car ownership is lower, so more people walk; perhaps infrastructure tends to be more neglected in poor neighborhoods; perhaps it's part of a piece with other risky behavior.)

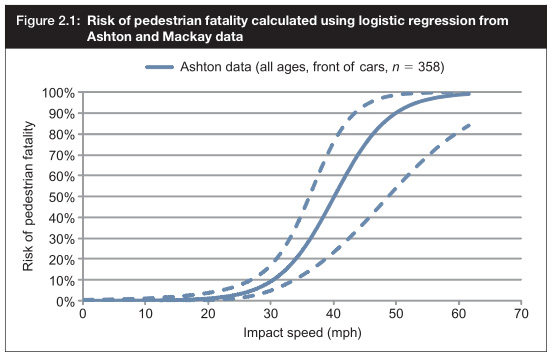

And pedestrians are more likely to be killed when a car is going faster. And something very specific happens when you get above 30 miles per hour.

There's other data with other findings, but generally speaking, things start getting really bad after 30 miles per hour: "This figure shows that the estimated risk of a pedestrian being killed is approximately 9% if they are hit at a speed of 30 mph. The risk at an impact speed of 40 mph is much higher, at approximately 50%."

Even at 35 miles per hour the risk doubles, from about 10 percent to about 20 percent. That Chicago's speed cameras do not tolerate light speeding ($35 for six to 10 miles over the limit) has been cause for consternation, but there's logic behind it, which the city's pretty explicit about.

The poor will be disproportionately affected by automated speeding tickets, as with any flat fine or tax. But poverty typically correlates with crime in Chicago: "In an examination of various factors including crime, income, race, language spoken, and walkability index, the strongest correlation found was between pedestrian crashes and crime."

It correlates quite dramatically, in fact (the crashes are specifically pedestrian crashes):

As with the cigarette tax, the red-light cameras do stand to make things harder on the poor. But they also stand to offer a much greater benefit to poor neighborhoods, reducing mortality in places where it's much too high.