Rich Cohen has written about a lot of things in a lot of different places: The New Yorker, The Atlantic, Harper's; the book Sweet and Low, about how his grandfather invented the artificial sweetener of the same name (which ended in a long, ugly family battle); Tough Jews, about the Jewish gangsters of early 20th-century Brooklyn; and he's a co-creator of the HBO series Vinyl, which stems from his reporting on the Rolling Stones and the music business.

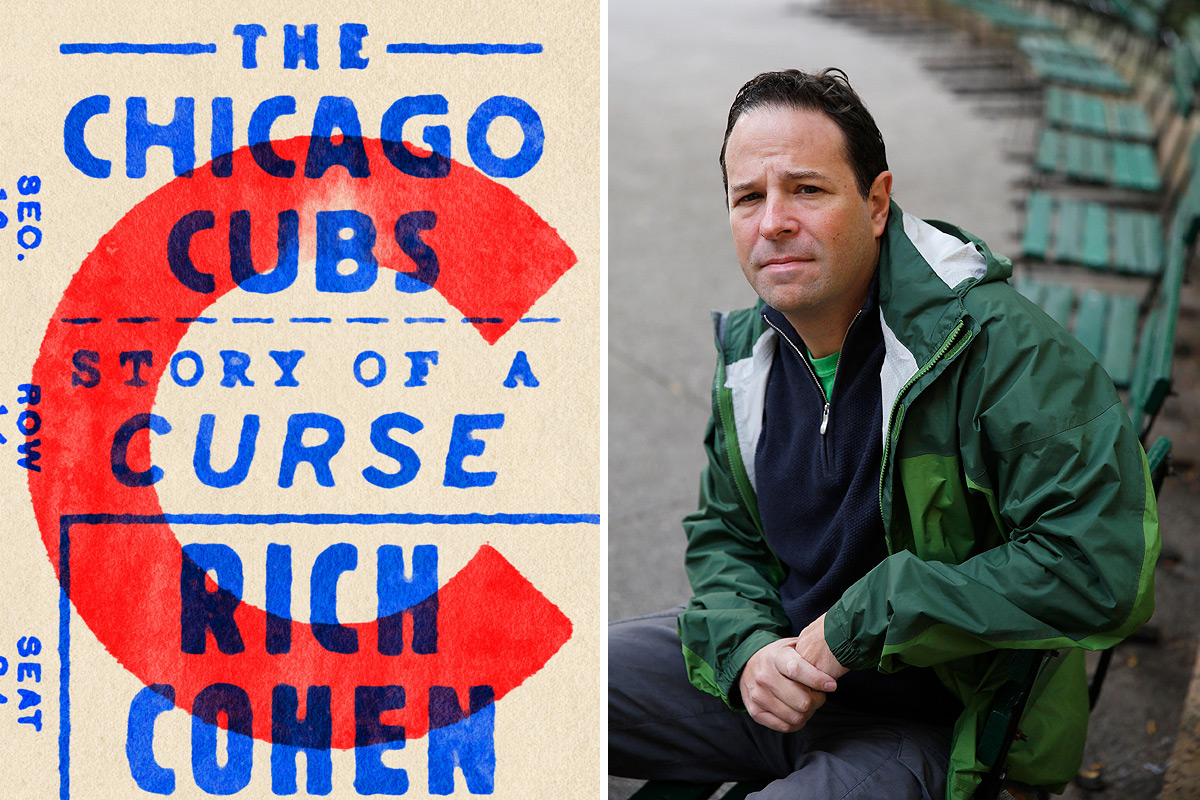

But he's also a native of the Chicago suburbs, and he's come back around to writing about the stars of his native land: First, with the 2013 book Monsters, about the 1985 Bears, and now The Chicago Cubs: Story of a Curse, which comes out today on the Farrar, Straus and Giroux imprint.

It puts the breaking of the curse in a historical sweep, and grounds the idea of the curse in what that history can tell us about it. Two turning points are particularly compelling, certainly more so than a goat. First is the ascension of Phil Wrigley to the ownership of the Cubs after his father died. Wrigley didn't know much about or like baseball, but he did know a lot about marketing and he did like making money. And the team came to reflect that: Wrigley skimped on the team, skimped on the nascent farm-system approach that Branch Rickey pioneered, skimped on coaches, skimped on bringing in new players, skimped on rewarding current players.

But he also helped make his namesake field one of the best places in the world to watch baseball, which it still is. Cohen quotes the always-perceptive Bill Veeck Jr., who worked as a special assistant to Wrigley before making his fame with several teams: "The [boss's] solution was to sell 'Beautiful Wrigley Field': that is, to make the park itself so great an attraction that it would be thought of as a place to take the whole family for a delightful day."

It worked. Wrigley is a destination, a shrine to the game, despite the less-than-sacred teams that have played there.

The second is the 1969 Cubs, when Cohen argues that decades of futility truly became a curse. The Cubs were up seven and a half games in June, but Cohen traces their downfall to a game on July 8, when centerfielder Don Young—"a twenty-three-year-old emotionally fragile rookie and the obvious weak link"—botched two fly balls in a 4-3 loss to the eventual World Series champions, the New York Mets. Both the manager, Leo Durocher, and the team captain, Ron Santo, lit into Young in the presence of reporters (Santo later called a team meeting and apologized). "Every member of the 1969 Cubs I have spoken to cites this game," Cohen writes, "as the pinch"—the moment when a good team without resilience falls apart.

But there are also stories of how Cubs management got it right. Dallas Green blew up the team, going from the valley of the Lee Elia rant in 1983 to the playoffs in 1984. Andy MacPhail, son of baseball royalty and two-time World Series winner as general manager of the Minnesota Twins, describes to Cohen the kind of team the Cubs need to win, and it sounds a lot like the team that Theo Epstein put together for 2016. Green and MacPhail had a sense of what it would take to get there, and it's why they were responsible for the moments when the team almost did.

And then there's Epstein. Cohen scores an interview with the Cubs' president, and devotes about 14 pages to it—mostly to Epstein's own words, which is its own thumbnail history of what went wrong with the Cubs and how he set about fixing it. It's a compelling passage that gets at who Epstein is, not just a dispassionate numbers wonk but also a manager with a keen understanding of personal and organizational dynamics. And after Cohen's long history of the team's failure, it suggests why Epstein was the man to end it.

I spoke with Cohen about his own personal history, how it intertwines with the team's history, and where both of them go from here.

How did you become a Cubs fan?

I grew up in Glencoe. I was born in 1968, so the early '70s was a wash, in the aftermath of the 1969 Cubs. One day my father took me to see my first baseball game, the Cubs playing the Cincinnati Reds. It was a great Cincinnati team, with all those guys who went to the Hall of Fame. The Cubs were ahead and the Cubs blew it, which was regarded as a typical Cubs experience, but I didn't know it. On the way home he made me promise that I would not be a Cubs fan. I wouldn't make that promise.

He grew up a Yankees fan in Brooklyn. He had this belief that a Cubs fan would have an inferior life, because a Cubs fan will believe that all human endeavor ends in ruin and futility, and will have lower expectations and expect less. Of course, because he was my father and tried to make me promise not to be a fan of the team, I became a Cubs fanatic very quickly.

And then it was this building, building, building until 1984, when I was a sophomore in high school, and I was a hundred percent certain they were going to win the World Series, and then they collapsed, and that was an epic, life-altering, personality-forming experience that I'm still grappling with.

Was your dad right?

He was definitely right that it forms your personality. Maybe it'll be different now that they've won the World Series and it's changed. I'm a panic-er, man. I always think oh, it's going to fall apart. Not just the Cubs, but everything in my life. I'm always prepared for how the thing's going to collapse in every situation in my life, and that's definitely as a result of being a Cubs fan.

My dad would say that means you have a diminished life. I actually came to believe, maybe because it was just my reality, it makes you have a better life, because you learn to accept or appreciate how great things are right now—because you don't expect there to be baseball played in the middle of October. You completely embrace the moment. A Cubs fan has to be a Buddhist by necessity. You just have to accept and appreciate great afternoons for being great afternoons and no more than that.

One of the most interesting things about the book is that it seems like that was designed-in by Phil Wrigley to this team. That he shorted the product on the field but made the field wonderful.

We all are super-critical of Phil Wrigley for doing that, that he made this Faustian bargain, traded excellence on the field for a great place to see a ballgame, and his idea being like, I don't really care to field a winner, so I have to give the fans something to come to the park. But of course, and maybe this is a result of my upbringing through 1984, you realize that even if you win the World Series, the next year's going to be crappy all over again.

The thing that Phil Wrigley gave you is, that thing, being a Cubs fan, and going to a Cubs game, is always excellent, regardless of how the team does.

Ernie Banks told you "the curse is not voodoo. It's fear." I'm curious if you agree with him."

Yeah. I do think that there's some actual reasons, but to the extent that there is actually a curse, it's like a mental block. They had to overcome this expectation to lose. That bleeds down to the players, and that was always the thing that was so mysterious to me. Every one of these guys is better than any baseball player you've played with, times ten. Every one is a champion at every single level, from the time they're little kids, probably. But when they get to the Cubs, something would happen.

It wasn't that they didn't have great players. Because they did. You look at that '69 team, the entire team's an all-star team. Same with '84. Multiple guys on these teams go to the Hall of Fame. But something happens right at what Christy Mathewson called the "pinch," where they fall apart. That's that feeling, that looking for a way to lose. You saw it in the Bartman game, everybody blamed the fan, but the team just fell apart.

When I interviewed Theo Epstein about it, he said, "I just saw it as a blown lead." Which is what it was. But for a Cubs fan, and through the institution, there's something almost otherworldly about it. To me the key moment was the look on Dusty Baker's face. Because Dusty Baker looked like he was thinking, "oh my God, it's true, there's a curse."

Theo Epstein had a bunch of smart ideas, and one was to bring up a lot of young players all right around the same time. So there was none of that, let's introduce one at a time, so they'll slowly be infected by the culture. If there's a curse, it's the culture, and you have to change the culture.

That's why it was so important that the Cubs were not only so talented last year but really, really young, because when you're young, you're kind of stupid, and that's what you need to be to break the curse.

It's interesting—the idea that these are incredibly well-trained guys who grew up with different fan loyalties.

They see how important everything is, and they feel how nervous everyone is. That's why it was so important that they like each other and they're so loose. Otherwise you're alone in it, instead of together in it.

One of the key things, I didn't put it in the book but I always think about it, even now—a good manager and a bad manager, to me, is like, Leo Durocher. Don Young drops those balls. And Durocher says "my fuckin' four-year-old kid (or whatever) could have caught those fuckin' balls." Hack Wilson—very similar situation—drops two balls in the World Series and the Cubs lose, and the manager says, "What do you want? He lost the ball in the sun? He didn't put the sun up there." That was Joe McCarthy, one of the greatest managers in history.

And that's to me like Joe Maddon. It was so great when they lost, I forget which game it was, it might have been the game when there was just one run scored in Wrigley Field, and he said, Well, it's just a great baseball game. Just happy to be playing baseball. That's his personality. It's a good match. That's why Theo picked him. He understands the incredible pressure of the situation.

That was a really interesting part of the book, your interview with Epstein, when he talks about how they really tried to target the minor leaguers and tried to make them more resilient.

Yeah, and bring them up together, so they couldn't be affected and ruined by the existing culture. They bring in a couple veterans, like David Ross, so they can be coaches on the field, but they're veterans from other teams, who won World Series in other places. That just made a lot of sense to me. You have to change the mindset of the institution.

One of the senses I got from the book was that Dallas Green was sort of the first front-office guy who really kind of got it.

I think that Leo Durocher kind of got it, but the difference was in that 1969 the curse wasn't really the curse yet. It was '69 that made it the curse. You're winning, you're ahead by nine games in August or whatever it was. That made it seem like something other than the team just being bad. On paper the Cubs were so much better than the Mets. They were great. They had Fergie Jenkins and Kenny Holtzmann pitching. They had a Hall of Famer at first base, a Hall of Famer at second base. The entire infield made the All-Star team. I think that collapse is what really turned the curse into the curse that we grew up with.

And that's something that Andy McPhail understood—you have to be good every year, because once you get into the playoffs, it's a crapshoot.

I was a serious baseball fan my whole life, and I never really got that. The thing that made me understand it was Moneyball. Once you're in the postseason, once you're into the seven-game series for sure, it's just luck. The thing about McPhail, he's super smart, I don't think the Cubs ownership would let him do what Theo Epstein did, which he gave credit to Ricketts for. He said it to me—the owners wanted the team to be good enough. They had a broadcasting interest in WGN to make them at least mediocre to put them on TV, and later they might be up for sale at any moment, so you wanted to make it seem like they had a chance to win the World Series in the next year or two.

Which is sort of how you end up with the teams of the late '90s, early 2000s.

And even with McPhail, I don't think they'd let him clean house. Every team's doing that now. The White Sox, just scourging players. They would never do that when we were kids. You'd never have a team where they got rid of all the stars. It's like in The Usual Suspects when Keyser Soze kills his own wife or whatever. When Theo Epstein let Nomar Garciaparra leave, you knew, Oh, this guy will do anything. That would never happen with the Cubs before. Durocher came in and he wanted to trade Ernie Banks and Ron Santo, but they wouldn't let him.

As fans get younger, and maybe it's because of the technology, fans are more fans of the franchise now. They used to be fans of the players. They know who's in Triple A, who's in Double A, who's a top-50 prospect in the minor leagues. You had no way to know that unless you got local newspapers from Des Moines or something. Because you have the internet, you can look at the whole organization in a way that would be unimaginable.

I think people are more tolerant. What I've noticed about White Sox fans right now is that they're not even really talking about how they have one of the worst records in baseball. They're talking about the young players and how they're going to be interesting to watch.

I think Theo taught people to watch baseball that way in Chicago. Maybe it preceded him, but that's what I mean. They look at it more like a startup, like you're watching a business, like we're a bunch of shareholders. For two or three years we're going to lose a lot of money, but then we've got these products and they're being tested, we'll get them into the stores a few years from now. The idea of trading a big star for a bunch of prospects who aren't in the majors, who might not even make it to the majors… I think it's a new way, a much smarter way, in that you have so much more information to watch baseball.

What do you think are the qualities of Epstein that made him be able to get through that?

He has a theory, and he sticks to his theory, and he's really a long-term thinker. That's why he'd be a good president. [laughs] He came in with a plan and he stuck to his plan, all the way to the end. Now he's got another plan.

It's funny, when I interviewed him—you read it—I used almost everything he said, because almost everything was interesting. [Ed. note: It was.] Which is this idea that there's Phase 1 and there's Phase 2. Phase 2 is winning, Phase 1 is building. And it's not only important to have a Phase 1 and a Phase 2, but to recognize when you're in Phase 2. So this year they traded away a bunch of prospects, and some people were grumbling about it. But when you know his plan, he's in the second phase. That's going to exist for three or four years, and then he's going to be back in Phase 1. You have this window when people are controllable, like Bryant and Baez and the other players. And then that's going to end. And then they're going to have to rebuild.