Related Content

The Lakefront Trail begins where Ardmore Avenue ends, just east of Sheridan Road, in Edgewater. The street passes between two metallic apartment houses that could have been transplanted from East Berlin, and beneath a tunnel of trees that forms a portal between the man-made world of high rises and the natural world of the lakeshore. The shadows of towers and leaves yield to the shocking sunlight of Kathy Osterman Beach, a dawn so bright it seems to herald not just the beginning of a new day, but a new Earth.

It’s Saturday morning. I am embarking on a bicycle ride down the entire Lakefront Trail — 18 miles, from the sign marked “BEGIN” to the “END” sign on 71st Street, in South Shore. Along the way, I hope to discover something of the essence of the city, because, as a South Side politician once told me, “the lakefront is Chicago” — the reason 2.7 million people have settled here. On a sunny day such as this, on the first weekend of summer, there’s certainly no better place to be in Chicago.

The 0.0 mi. marker notes that the trail was “Generously improved by Ken Griffin.” Before ditching Chicago for Miami, the hedge fund billionaire donated $12 million to separate the trail into bicycle and pedestrian lanes, then another $5 million to repair lake erosion. He didn’t even ask to rename it The Ken Griffin Lakefront Trail. That’s philanthropy. The conflict between runners and cyclists has not been entirely resolved, though. Beside the “WELCOME TO EDGEWATER” tunnel, with its colorful, geometric tiles, I am flagged down by a man in a yellow jersey. He has been sitting in a golf cart under a tree.

“What’s going on?” I ask.

“It’s a 5K run/walk. This is the turnaround. I don’t want you to hit anyone.”

Back-of-the-pack walkers file around orange cones.

“I don’t want to hit anyone. I thought the bike and the running lanes were separated now.”

“They usually are, but there are these quarter-mile stretches.”

Here, the cyclist glyph and the runner glyph are divided only by a yellow stripe, although they diverge again after the tunnel. It’s going to take more than $12 million.

Just south of Foster Avenue Beach, in the immigrant neighborhood of Uptown, a soccer ball bounds away from a playing field, coming to rest under a tree. I stop riding, pick up the ball, toss it to a pursuing goalkeeper.

“Is this the refugee game?” I ask the keeper.

“No English,” he replies, through a mouthful of broken teeth. “No speak English.”

It’s the Refugee World Cup, on World Refugee Day — eight teams, from eight corners of the world, competing in the one sport they have in common. I just missed Mayor Brandon Johnson, who performed the ceremonial duty of opening the games. Daniel Hudson, of the Syrian Community Network, recaps the mayor’s remarks.

“He was commenting on how Chicago is a place that welcomes everybody, the regular spiel, and how it’s a Chicago sport,” says Hudson. “I actually think this is more of a basketball town.”

Hudson, who is wearing a pink faux fur hat, grew up as the son of English teachers in Yemen, so he can translate for Arabic-speaking refugees.

“We’ve also got Mandarin, Spanish, Pashto…” he recites.

The lakefront does not just draw all Chicagoans, it draws the entire world. On the bike path, dozens of cyclists in Wounded Warrior jerseys cluster around a medical van. They’re on a water break, in the midst of a ride for the Wounded Warrior Project, a charity for post-9/11 veterans.

“Chicago is one of the big events of the year,” says Jered Holder, an Army veteran and Soldier Ride Specialist from San Antonio. “Chicago, New York, Key West, and San Antonio. We started at Firehouse 18 on Blue Island and we’re going 28 miles, to Glencoe.”

The Montrose Point Bird Sanctuary is at the end of a peninsula that extends so far into the water it seems more a part of the lake than the city. Bicycles are banned here, so I walk through its wild, shaggy meadows, planted with prairie grasses. I am proud of myself for spotting a red-winged blackbird, until I meet Shawn Sakai, a real birder, wielding a camera with a telephoto lens. Already that morning, Sakai has photographed a yellow warbler, a vireo, a scarlet tanager, an American redstart, and of course, a red-winged blackbird, which is “everywhere.” In this bird sanctuary, it’s possible to spot 50 or 60 of the 969 species on the American Birding Association checklist.

This morning, Sakai is a lone birder, but “it can get very crowded in the early spring — April, early May,” he says. “This is on the migratory path. A month ago, there were dozens of people with cameras.”

Sakai points into the foliage, at a tiny bird, barely bigger than a thumb, bobbing from branch to branch.

“Yellow warbler,” he says. Only a trained eye could have spotted that.

The signs nailed to the facade of the Park Bait Shop, on Montrose Harbor, advertise nightcrawlers, redworms, minnows, coho boat tackle, and coffee. It’s almost noon, and I haven’t had my morning coffee. Inside, Stacey Greene steps out from behind a glass display case of sinkers and bobbers, and pours me a styrofoam cup. Greene took over the bait shop from her father, Willie Greene, a legendary lakefront character who ran it from 1957 until his death in 2012. “Give me half-a-dozen Montrose fishermen, put ’em anywhere in the world, and they can catch anything,” Willie liked to say. The shop itself is even older: The North Woods lodge wood-paneling on its walls and the door of the walk-in cooler dates back to its construction in the 1930s.

“We’re the longest continuously run bait shop in the state, maybe the country,” says Stacey, who gets out of bed every morning at 2:50 a.m. to open at 4. Perch season opened a week ago, but not a lot of anglers are catching the lakefront’s most popular fish: “These northeast winds have had things so garbled up.” Willie used to complain that Lake View was no longer a fisherman’s neighborhood, not like in his day, during the Depression, when Montrose Harbor was fished by regulars with nicknames out of Cannery Row: Harry the Jap, Diversey Shorty, Coffee George, Uncle Henry.

“Marine Drive, Lake Shore Drive, big buildings like that — they don’t produce the people who fish,” Willie would say. “They may own a place at Lake Geneva, but they’re not the ones that do the fishing.”

The Park Bait Shop has adapted to its neighbors. A young man walks through the door, looking for sunscreen for himself and his girlfriend. Stacey lets him pay with Zelle, despite the “CASH ONLY” sign.

On North Avenue Beach, volleyballs bounce above the waterline. Blue umbrellas blossom in the sand. A lifeguard poses dramatically atop his wooden tower, beneath a green flag. The North Avenue Beach House was designed to look like an Art Deco ocean liner. It was originally built in the Art Deco era — 1939 — and became such a landmark it was replaced with a replica in 2000. Unfortunately, the rooftop restaurant, Castaways, is closed for renovations, so I have to forage on the beach for lunch. A pina colada stand sells tacos for $5. It also sells Pineapple Deluxe Pina Coladas for $16 — virgin pina coladas.

“The city doesn’t let us use rum,” a server explains. “They don’t want people walking onto the beach with alcohol.”

Winning a concession from the Chicago Park District reminds me of Henry Hill’s line from Goodfellas about the perks of becoming a made man: “It’s like a license to steal, a license to do anything.”

While I wait for my tacos, I wander down the shore to the Y2K Beach Party. That name probably sounded hep in the 2000s, as did Flo Rida’s “Low,” which is booming from a speaker. For $20, I can watch a volleyball tournament, stand under a gun spraying foam, and participate in a Panic! at the Silent Disco — dancing while wearing headphones. “It’s like a license to steal.”

Navy Pier is a tourist trap, with a ferris wheel and a children’s museum and a Kilwin’s fudge shop, but it’s also the first place on the Lakefront Trail that sells beer. Harry Caray’s Tavern even gives me a new beer, when I don’t like the first one I ordered. A 312 Lemonade Shandy sounds refreshing during a hot bike ride, but tastes like Lemonheads candy.

“I should have known better than to drink beer with fruit in it,” I complain to the bartender.

“Is the lemonade shandy not to your liking?” asks the bartender, who is Irish.

“Too sweet.”

“I’ll talk to my manager and see if I can get it off your tab.”

I still want to drink locally, so he pours me a 312 Urban Wheat Ale. That’s real beer.

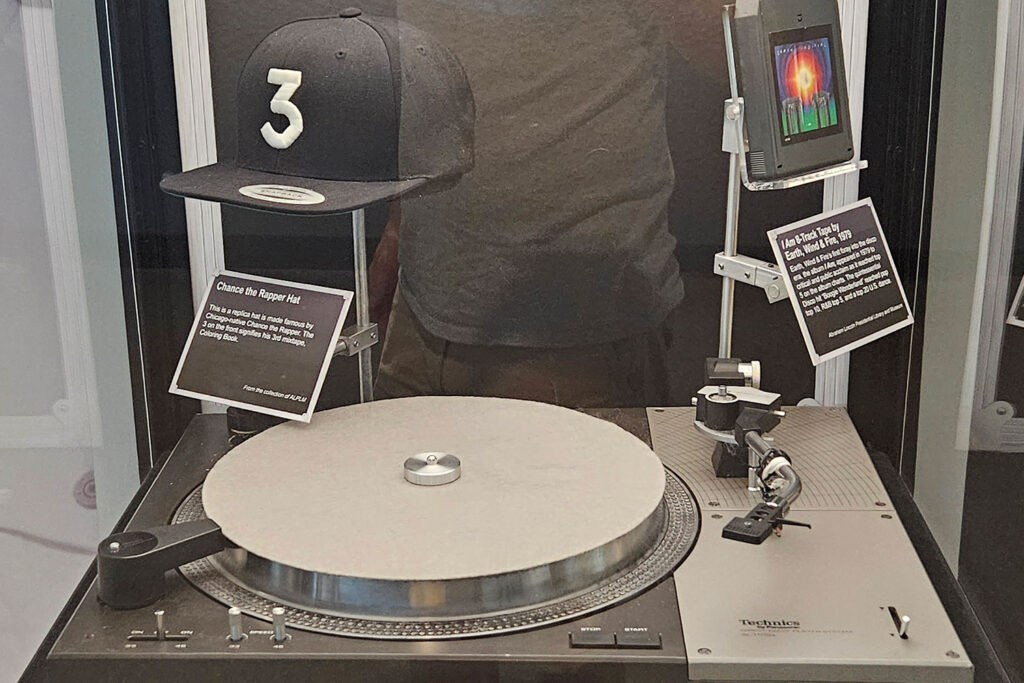

I’m at Navy Pier not just for beer, but for State of Sound, an Illinois music exhibit I first saw at the Abraham Lincoln Library in Springfield. The exhibit is waaaay in the back, which is a long way at Navy Pier — past the fudge, past the Garrett’s popcorn — and is missing several important artifacts I got to see in Springfield, including Dan Fogelberg’s acoustic guitar and Steve Goodman’s Cubs jacket. On display instead are Rick Nielsen’s baseball cap, Frankie Knuckles’s turntable, and Eddie Blazonczyk Jr’s Best Polka Recording Grammy. It does, however, point out that Illinois is the state where “Americana was born,” crediting Decatur’s Alison Krauss, Belleville’s Jeff Tweedy, and the Waco Brothers, even though they’re from England.

The Lakefront Trail’s halfway point is at 500 South Du Sable Lake Shore Drive. I stopped to take a photo of the 9.0 mile marker. I’ll also stop writing here, and tell you about the South Side next time.