It's a big couple months for Studio Gang: the Art Institute's exhibition devoted to the Jeanne Gang-led shop opened yesterday, and their initial plans for Northerly Island were recently greenlit with construction scheduled to start in November.

The best introduction to the comphrehensive plan is still Studio Gang's introduction (PDF), which explains the busy design in all its environmental and technical complexity, breaking down the conceptual layers that combine to create the entire framework.

It looks like a large, fairly elaborate city park, and much attention has been given to the physical infrastructure devoted to humans, like the concert venue. But beneath and around that is a natural infrastructure:

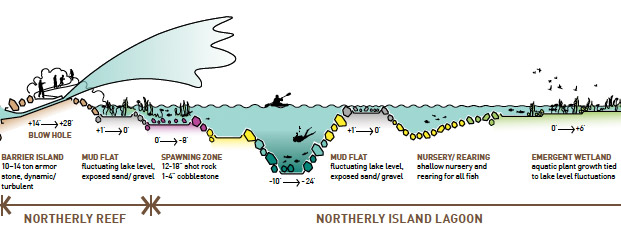

Around that skeleton are species-specific habitats—"bioengineered breakwaters" designed to encourage native fish populations: "Conceptual designs that mimic those areas known to attract and keep fish will include coastal wetlands, rock barriers, deep water habitat, substrate modification, flow diversion structures, increased plant and forage fish diversity. A cutaway shows the structure visitors won't be able to see:

There's a similar gradient of avian habitat:

And human habitat:

The north side of the island would feature a beach, the existing harbor, a music venue, the Adler, a picnic grove, and more, the "active" half; the south, a "camping bowl," reef walk, bird-pier, and "informal paths," the "passive" side. It's not so much about devoting half to nature and half to man, but changing the balance from one half to the other. Studio Gang's vision is as much about the parks tradition of Jens Jensen, the comparatively undersung genius of the city's park system, as it is about Daniel Burnham:

The "Prairie Style" of landscape gardening practiced by Jens Jensen and his contemporaries Ossian Cole Simonds and Alfred Caldwell, was as much about conservation as it was about aesthetics. For individuals like Jensen and Simonds, their motivations grew out of a sense that the natural landscape, especially that of the Midwest, was changing drastically. In the growth around Chicago and other cities of the region, the unique natural features that gave each of these areas their distinctive character were in danger of being irrevocably lost. The intent of a prairie style garden was to help build an appreciation for the beauty of the natural landscape and to encourage actions to protect what natural areas remained.

[snip]

The destruction of these nearby wilds is what Jensen saw as one of the great tragedies of our country and it was one of the things that motivated many of his later conservation efforts through the Prairie Club and the Friends of Our Native Landscape. In his article, "Nature the Source" (Jensen, 1927), Jensen stressed that nature is the only true "source" for studying landscape gardening. For Jensen, nature provided "more real depth" and "more mystery" that fueled the subtle artistry of his design work . His careful handling of plant composition, stone work, light and shadow, textural contrasts, and outdoor space drew its strength from these in-depth studies of natural patterns. Jensen's parks and gardens became idealizations of the regional natural heritage of the Midwest.

Jensen's plans for Columbus Park (now the greatly diminished Austin Park), which he considered his masterpiece, recall Studio Gang's plan for Northerly Island:

Incorporating the natural history and topography of the site, Jensen created series of rolling hills, similar to glacial ridges, that encircled the flat, central portion of the park. Within this area, following the traces of the ancient lake beach, Jensen created an artificial prairie river. He included two waterfalls of stratified (layered) rock over which water trickled as if from springs into two brooks meandering and merging into a larger, natural looking lagoon or waterway.

[snip]

On the west side of the park, facing the setting sun, Jensen created a flat horizontal meadow. This representation of a natural prairie provided a golf course and ball fields. The area included prairie flowers and shrubs. To simulate forest groves, Jensen used massed elms, ash, maples, hawthorns, and crab apples. Along the brook he planted rushes, cattails, hibiscus, and arrowheads.

Jensen slowly shifted the urban park from the idealized European idyll to a still idealized and perfected but very Midwestern landscape. Northerly Island takes that further still—embedding not just the landscape but the entire ecosystem into the island, reflecting our vastly increased understanding of it. And it's a natural landscape that includes the urban hand of man.

As Ben Meyerson writes, the full plan is vastly ambitious, and could cost in the high-eight or low-nine figures, bringing the haunting specter of congressional authorization (the first step is small and comparatively inexpensive). So don't wait up. If completed, however, it will be a remarkable work. If the Bloomingdale Trail is Chicago's High Line, Northerly Island will be our very 21st century Central Park.

Images: Chicago Park District/Studio Gang