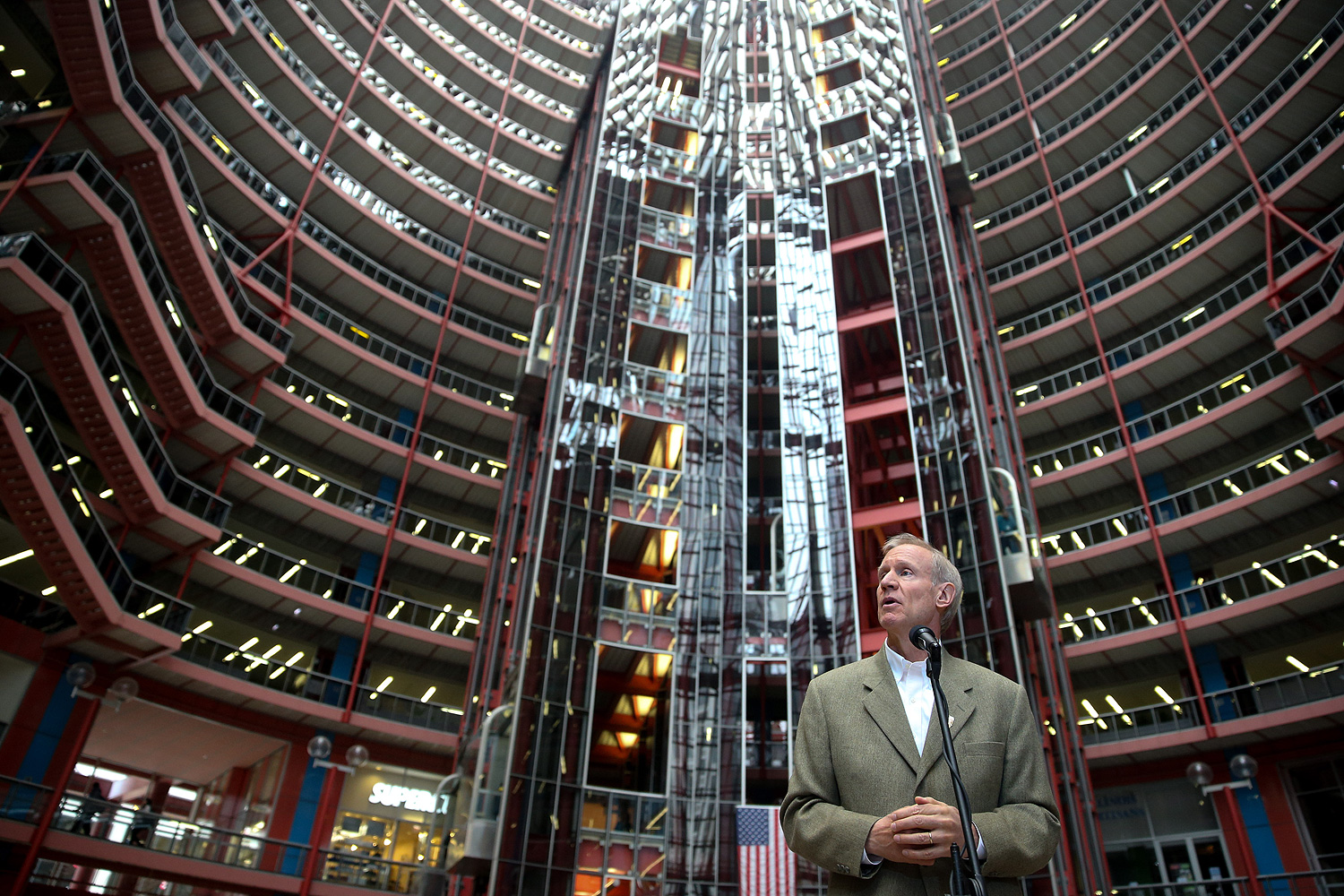

The other day, Bruce Rauner announced that he wanted to sell off Helmut Jahn's Thompson Center, the echt-'80s state building, transit hub, and bell jar in the Loop. The structure has remained controversial since it opened and was christened as the State of Illinois Center in 1985 (it would change to Thompson in 1993). The title of the Tribune review by architecture critic Paul Gapp when the center opened was: "Helmut Jahn's State of Illinois Center Is: 1) Breathtaking? 2) Impudent? 3) Outrageous? 4) Idiosyncratic? 5) All the Above."

30 years later, the answer is still No. 5.

Its admirers appreciate its impudence in the face of its companions, the neoclassical City Hall and the grimly Mies-ian Daley Center. As Gapp wrote, "the Daley Civic Center is probably the most brutishly powerful International Style skyscraper in the United States—a monolithic, brooding building that seems to stand guard over the Loop like a gargantuan armed knight." It always puts me in the mind of the monolith from Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey, which is maybe not a good look for a government building.

By contrast, the Thompson Center was supposed to be transparent, colorful, and open, a panopticon for the people. It was built as a gigantic open-office plan where employees could see, hear, and even smell goings-on across the atrium and up and down floors. "Binoculars seem to have become popular office paraphernalia," Bonita Brodt, a reporter for the Tribune, wrote in 1985. "One morning last week, [Beatrice] Arkema was one of 13 state employees who, with binoculars in hand as they lingered on the stairways, sheepishly admitted watching government at work."

And it wasn't just sightlines the building opened up. "The glass elevators run up and down on cables with the speed of a stomach-churning carnival ride," Brodt wrote. "Their operation is accompanied by a lot of noise, a loud and annoying whir. 'It is really loud,' said Norma Gross, a bilingual specialist with the state's Department of Education. She sits at a desk on the 14th floor in an open area near the banks. 'To talk on the phone here is impossible.'"

As a historian friend of mine described it, it was "totally in line with [Governor James] Thompson's style—very interested in the arts and practicing symbolic politics." And symbolism is a really important part of architecture! But so is actually functioning for the people who work there. And initially the building was a huge failure at that.

First, the elevator noise had to go. In June, Paul Gapp reported, "an acoustical shield has been designed to squelch the sound at its source…. It will be installed after architect Jahn rates it esthetically acceptable." The next month, a compressor went out in the building's dysfunctional air-conditioning system, allowing temperatures to hit 90 degrees. Employees brought in fans to cool themselves, at least until it got so hot they were sent home, and set up umbrellas to prevent glare from making their computers unreadable, "a result of the building's single-paned (versus double-paned) glass," according to the Tribune. The paper reported in 1986 that the estimates to power the building were off 65 percent and around $500,000 in the building's first year.

"The media darling [Helmut Jahn] has created a monster that is virtually impossible to keep temperate," wrote William Lavicka, president of the Structural Engineers Association of Illinois, in a letter to the Tribune in November of 1985. "Here is a case where government has let a stylist run amok and create a $200 million building that no responsible engineer or architect could ever save from probable heating and air-conditioning disaster."

But that was a long time ago. How is it now?

"I've worked in a lot of offices downtown," says Matthew Glavin, who worked in the Thompson Center as a state employee from 2012 to earlier this year. "And it is the worst. It was never the appropriate temperature. There was always a fight for the fans."

"It's either very hot or very cold," says an attorney who has worked there for five years and wished not to be identified. "All the heat for the floor comes into my office, and the same thing happens in the summer, because the A/C is designed to do one thing"—that is, cool and heat an almost entirely open-plan office.

Retrofitting the interior to make the building less radically transparent was, at least, supposed to give employees a bit more privacy and a bit less distraction. Like so much else with the building, it didn't quite work. "They built a lot of offices," he says, "where the walls are plywood that you can hear through."

The same goes for the electrical system. "There are very few plugs on the walls," he says. "There are random outlets coming up from the ground, and power strips in a lot of places. It's ad hoc."

But it's not that the power strips ruin the view.

"The carpets are very old," he says. "There's duct tape on the floor where it's torn."

Glavin has the same complaint. "The carpet is quite literally held together with duct tape. It's my understanding that the carpet was the original carpet. The building felt tired."

And yet, despite it being the worst downtown office building he's worked in, Glavin has some affection for it. "I do think it's become a punching bag. No other building would be a good place to work if it was neglected for 30 years." he says. "I like the fact that it was completely different, that it took a chance. Do you know the Pompidou Center in Paris? It reminds me of that."

He'd like to see it repurposed. So would Jahn, who released a statement lamenting how the "symbol for the openness and transparency of state government" fell into physical neglect. He suggested that the "best way to save the building" is to hock it, "marketing the large floor plates to innovative tech companies." How's that for architectural symbolism?