The Brown Line is the bourgeoist of the main L lines, because it’s the only one that does not pass through a poor neighborhood. It did once, but that neighborhood is now gone. A journey along the Brown Line is an excellent way to learn how much Chicago has changed over the last 25 years.

I began my Brown Line excursion at Sedgwick, where the tracks leave the Loop and begin angling toward the Near Northwest Side neighborhoods that they have done so much to gentrify. The Sedgwick stop is a few steps from the Old Town Ale House: Established in 1958, it’s one of the few Brown Line institutions that has never changed, never will change, and never wants to change. Just a few blocks west, though, the tracks pass by the corner of North and Halsted streets, once the site of Cabrini-Green.

Cabrini-Green was not just any housing project, it was the project that embodied every problem with public housing in Chicago: inspiration for the sitcom Good Times, home for three weeks to Mayor Jane Byrne, and — in 1992 — site of the murder of 7-year-old Dantrell Davis, killed by a sniper who was shooting at a rival gang member. Davis’s killing became known as “the shot that brought down the projects”; it led to the demolition of Cabrini-Green and most of the Chicago Housing Authority’s high-rise buildings. The CHA still runs the Flannery Apartments, a senior citizen community, on the site, but most of Cabrini-Green has been replaced with mixed-income housing. Across Halsted is the New City shopping center, with a Dick’s Sporting Goods, a Mariano’s, an AMC Theater, and Earl’s Kitchen + Bar — businesses that would have been beyond the means of Cabrini-Green’s 15,000 low-income residents.

At Armitage, I stopped for lunch at Chicago Bagel Authority, the trackside delicatessen. I had to order the Chicago Party Aunt. It is, as far as I know, the only sandwich inspired by a Twitter account. Its ingredients: garlic bagel, tuna salad, giardiniera, onions, smoked cheddar, lettuce, tomato, mustard.

“Everything vile you can think of is in there,” owner Gary Gibbs told me. “Fish, giardiniera. Everything I think would give you breath that you need to take care of. It tastes awesome.”

The sandwich does indeed have a smoky edge, and its pungent ingredients leave the same aftertaste as an encounter with the Chicago Party Aunt herself.

“The person who does the account reached out and wanted a sandwich and they were very pleased,” Gibbs explained.

Chicago Bagel Authority once sold a salad called The Trixie — “when that term was more in vogue” — because Armitage is probably the Trixiest of the CTA’s 145 L stops, if that’s an adjective.

When Chicago Bagel Authority opened 25 years ago, “Lincoln Park was a little more of a bohemian community — resale stores, antique shops,” Gibbs reminisced. “Now it’s sort of a mall of boutiques.”

Gibbs’s deli shares Armitage Avenue with a handbag shop, a Peruvian import store, an Indochino, a Tie Bar, and a tuxedo rental emporium. Gibbs broke into a song called “White People, Brown Line,” which a friend of his wrote for a musical comedy class at Second City: “I work out at LPAC/Doing fine/White people, Brown Line,” he sang.

I also saw a lot of white people at Southport. I fit right in on the Brown Line. First, I had a coffee at Capital One Cafe, a combination bank and coffee shop where Capital One card users get half off. Then I saw the Farmers Food Community Low-Line Market setting up directly beneath the station. (Farmers Markets are No. 5 on the Stuff White People Like blog.)

“How is it working under an L stop?” I asked Jacob Katz-Berger, a baker standing in front of an array of loaves and rolls as artistically arranged as a magazine ad.

“How is what?” Katz-Berger asked, since I had asked him the question just as a train pulled in.

“How is it working under an L stop?”

“It’s bittersweet,” he said. “It’s loud, but that means people are coming. Four, five o’clock, that’s when it really picks up here. This is our first season here. We’re trying to get to the point of having a brick-and-mortar store.”

I bought a slice of monkey bread, then wandered past a candle stand, a produce stand, and a cheese stand until I met Mike Felten, a white-haired guitarist in a fedora and a green Fillmore East t-shirt whose songs must compete with the roar of rush-hour trains.

“It’s great,” said Felten, who describes his sound as “white-boy blues” – B.B. King, Howlin’ Wolf, John Prine, Steve Goodman. “You do extended solos, just doodle around until it goes away. Some of the suburban markets I play at are in train stations, so they have freight trains coming in. Here, I do have a little condensation dropping on me.”

Felton broke into his biggest hit, “Where’d You Get That Dress?,” a song on one of the 10 CDs he sells. Hear his music at landfillrecords.com.

As I walked away from the farmers’ market, I thought of getting a beer, but the closest bar, Crosby’s Kitchen, charges $6 for a bottle of Budweiser. That’s Brown Line pricing. I bought the same beer on the Northwest Side for $2.25.

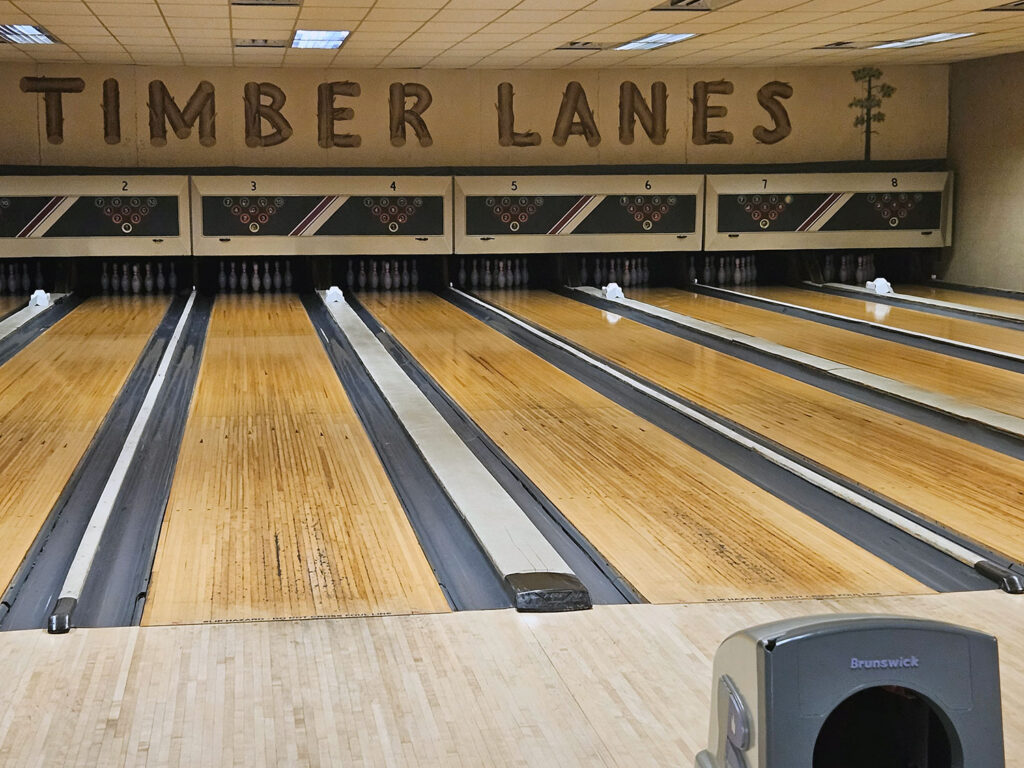

Some places along the Brown Line don’t change, even as everything else changes around them. Bob Kuhn bought Timber Lanes, a bowling alley at the Irving Park stop, on June 3, 1985. It’s one of 10 alleys left in the city, and its classic, eight-lane layout has made it the site of movie shoots, TV ads, and music videos.

“This was a very terrible neighborhood back in the ’80s,” Kuhn said. “There were a lot of dilapidated buildings and old structures. Since then, the average household income has gone from $30,000 to $250,000. Within a block of this building, there’s $15 million houses. The Brown Line did a lot for this area — the convenience of the transportation to the Bears, Wrigley Field. This piece of land wouldn’t be worth $3 million if it wasn’t 125 feet from the Brown Line.”

Timber Lanes was the site of a transformative moment in Brown Line History: In 2011, it served as the headquarters of Ameya Pawar’s campaign for alderperson. Pawar, the first Asian-American on the City Council, replaced Gene Schulter, first elected in the 1970s, when North Center and Lincoln Square were dominated by German-Americans. The newcomers to the neighborhood were educated, tolerant, and accepting of Pawar’s “ethnic background,” Kuhn said.

Kuhn sold me a pint of Schlitz for $4 — very reasonable by Brown Line standards — then offered me a bowling lesson, since the alley was empty at noon. Kuhn has rolled two 300 games. Keep your feet together, bend your knees, hold the ball away from your body, aim at the spot between the second and third arrows, he instructed. My first two attempts were gutter balls, but then I rolled a strike.

“The ball won’t lie to you,” Kuhn said. “Your wife will lie to you, your kids will lie to you, but the way you throw the ball is what you’re going to do. If you don’t like it, you’ve gotta change.”

At Lincoln Square, under the tracks by the Western stop, a group of rural-looking men in baseball caps were setting up carnival games for the weekend’s Chicago German-American Oktoberfest: Roller Ball Derby, Balloon Derby, Hippo Water Race, Goldfish Duck Pond, Long Range Shooting. The Oktoberfest, which includes the Von Steuben Day Parade made famous in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, is a remnant of Lincoln Square’s German past. On the 4500 block of Lincoln Avenue, the Niedersachsen Club is next door to the Old Town School of Folk Music — the neighborhood old and new.

Jason Marrotta, owner of Kaye Brothers Amusements, has been working the Oktoberfest for most of his 44 years, since his father first brought him here.

“It was a predominantly German neighborhood with grocery stores,” said Marrotta, a big man who sounds a lot like Carl Spackler in Caddyshack. “It’s trending with the times. It’s not just Lincoln Park. You can come all the way to Lincoln Square. There are a ton of families in this neighborhood.”

Last week, Kaye Brothers was in Michigan. Next week, it will be in Kentucky. Does Marrotta consider himself a carny?

“Absolutely,” he asserted. “I own a carnival company. For a long time, it was derogatory, but now I don’t mind. I know how much I make. Call me what you want.”

Lincoln Square is the brownest of all Brown Line neighborhoods. It fits the definition of a high-class shopping district: most of the stores sell things their customers don’t need. If Maslow had created a Hierarchy of Retail, Lincoln Square would be at the top. Disposable income can be disposed of on action figures at Quake, vinyl records at Laurie’s Planet of Sound, perfumes and lotions at Merz Apothecary, and books at the Book Cellar. When Suzy Takacs opened the Book Cellar 20 years ago, Alderman Schulter was trying to recruit an independent bookstore to fill a niche in the neighborhood.

“I think we have a good mix of restaurant and retail here,” Takacs said. “The Old Town School and the Davis Theater, that’s more reasons to be here.” And, of course, the Brown Line: “People have to have a reason to get there.”

Kimball, the last stop on the Brown Line (the name that appears on the trains’ marquees) is only a mile-and-a-quarter west of Lincoln Square, but it’s strikingly different, economically and sociologically. The Chicago River separates upper-middle-class Ravenswood Manor from lower-middle class Albany Park. Roosevelt High School is across the street from the station. So are strip malls with practical, workaday businesses: laundromats, dental clinics, “Seguros de Auto.” Most of the faces on the sidewalk are Latino or Middle Eastern.

I paused outside Huddle House Grill, a 24-hour diner, to study the menu through the window. Like a Roseland caller, waitress Sheila Diaz rushed outside to sell me on the supper time experience.

“Come on in and try it,” she shouted.

I stepped into a narrow diner with five booths and ten stools. Diaz persisted in her hard sell: “This place has been here for a hundred years. We’ve got omelets with feta cheese, pork chops. More people should try this place!”

I had traveled far. I was hungry. I ordered a Denver omelet, since diners that serve breakfast anytime always do breakfast best.

“We have delicious breakfasts,” Diaz said enthusiastically. “We’ve got so much. A lot of people order the hot dogs.”

The Huddle House is across the street from an L stop, but doesn’t get a lot of commuter traffic. Its diners are tourists, people visiting the old neighborhood, or people like me, who wandered down the street, and had to look inside.

“Sometimes I get lucky like I did with you when I go out there and see people looking,” Diaz said. “I just had two people from Arizona. People love diners. It’s a dying breed. This is a real Chicago diner.”

I ate my omelet to the tune of “Listen People” by Herman’s Hermits, playing on Diaz’s favorite oldies station. Diaz is 65. She’s old, the music is old, the diner is old.

“You should see me sittin’ here beboppin’ to the music,” she said. “It reminds me of being a young girl, the kind of music I grew up with.”

I crossed Kimball Avenue, to get back on the train. Outside the L stop, a man was sleeping under blankets on the sidewalk. I had not seen an unhoused person at any other Brown Line stop. Only here, at the end of the line.