Fifteen miles down Michigan Avenue from the Magnificent Mile is another, less magnificent mile. Or half mile, really. The shopping strip along Michigan Avenue between 111th and 115th streets, in Roseland, is the remnant of one of Chicago’s great neighborhood downtowns. It was once anchored by Gatelys People Store, a South Side Marshall Fields that called itself “the biggest store on Michigan Avenue.” Gatelys moved to Tinley Park in 1981, following white flight to the suburbs, but its sign loomed over Roseland for decades, until a fire destroyed the building three years ago.

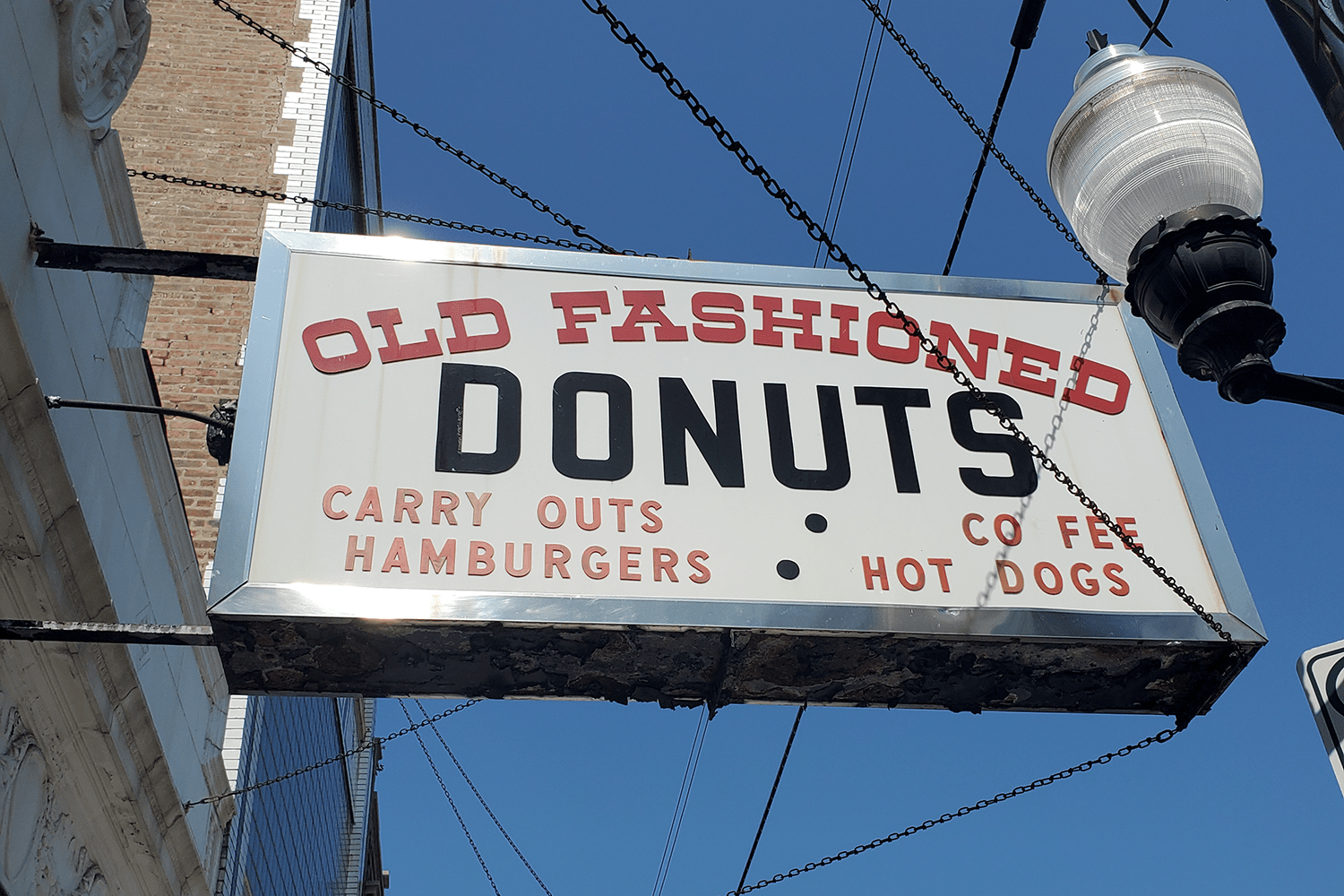

Before we get into a story about neighborhood decline, though, let’s talk about the one institution that still makes Roseland magnificent, and a must-visit for any Chicagoan. That would be Old Fashioned Donuts, 11248 S. Michigan Ave., which has been in business 50 years and doesn’t look any different than the day it opened. Head through the glass and wood door, with the metal tab labeled “PUSH,” and you’re in a diner with a few stools and an RC Cola menu board spelling out the bill of fare in plastic letters of varying sizes. 1 DONUT $1.14. MALTS $3.20. PIZZA PUFF $2.50. The air is scented with McIntoshes and oil, the smell of Old Fashioned frying its famous apple fritters, a family-sized treat at 850 calories (this magazine named an iconic Chicago eat last year). Buritt Bulloch, the 83-year-old founder, still gets to work at 6 a.m. every day to make the donuts.

Even if you show up late on a Saturday, after all the fritters are sold, you’re still going to eat the best doughnut in Chicago. Try the glazed cake doughnut. Bite through the sweet crust, into the softest, flakiest ring of fried dough you’ve ever eaten. That’s why Old Fashioned is one of the few survivors from Roseland’s glory days.

“We get people from all over the city,” said Tina Bulloch, the founder’s daughter. “The older people still come in here.”

The Army-Navy store closed, though. So did the pet store. The Ranch, a Western-themed steakhouse which was decorated with black-and-white photos of old cowboy stars, such as Roy Rogers and Tom Mix, went out of business during the pandemic. One of the few other survivors is Edwards Fashions, 11363 S. Michigan Ave. Edwards sells Dobbs hats, Stacy Adams shoes, and technicolor sportswear — everything a man needs to dress up for the Saturday afternoon barbecue and the Sunday morning church service. In the 1970s, when owner Ledall Edwards’s father opened the store, Roseland “was booming: clothing stores, shoe stores, grocery stores. It was bustling with pedestrian traffic. Ninety percent occupancy. Now, some blocks are less than 10 percent.”

Edwards blames the lack of business not on white flight, but on the 1998 vote to make Roseland a dry neighborhood, which was encouraged by Rev. James Meeks of nearby Salem Baptist Church. That closed 27 liquor stores and taverns — and ended up taking a lot more businesses with it.

“There was nightlife around here: Why Not Lounge, Famous Lounge,” Edwards said. “That’s gone. When that happened, not only did those businesses close down, so did businesses that fed off that.”

In the 1980s, Barack Obama did much of his community organizing in Roseland. The office of his Developing Communities Project was in the basement of Holy Rosary Church on 113th Street, across the street from Palmer Park. The one time Obama met his idol, Harold Washington, was at the ribbon cutting for a Mayor’s Office of Employment and Training Center in Roseland, for which the DCP had lobbied.

Today, most of the businesses in Roseland are what could be described as urban fashion boutiques. They sell distressed jeans, cartoonish t-shirts, and caps and jerseys from professional sports teams. On a recent Saturday afternoon, Trey Patton stood outside Stop & Buy Sports, 11125 S. Michigan Ave., practicing the Roseland tradition of “calling.” Callers stand on the sidewalk outside stores and keep up a patter, encouraging passersby to come inside and shop.

“I’ll look out for you,” Patton called to the sidewalk traffic. “Nice deals. Good deals. Nice sales. Check me out.”

When Patton finally hooked a customer, he held the door open.

A caller’s function is to serve as an intermediary between the neighborhood and the immigrant merchants who control most of Roseland’s commerce. A legendary caller named Blue, who knew everyone and their cousin in Roseland, used to get $40 a day and a 15 percent employee discount to do his act outside Sana Fashion at 112th and Michigan.

“It’s always people from the neighborhood,” Patton said. “I think it’s their way of giving back to the community. If they hire us, they know we know everyone in the neighborhood.”

However, Mike Mamood, Stop & Buy’s co-owner, denied that he had ever hired Patton — or the two friends he was hanging out with in front of the store. He also denied that he is an Arab, as Patton claimed. He is from India.

“They lie,” Mamood said. “He don’t work here. They’re hustling. Selling squares.”

Patton then came into the store himself and bought a pair of black pants, negotiating a discount in exchange for his calling services.

“He said, ‘You see me every day, give me a discount,’” Mamood said. “So I gave him a discount. They hang out outside. I gotta open the store, so I let them. What can I do?”

Mamood doesn’t live in Roseland. He lives on the West Side. What can he do? He has to stay on the locals’ good side.

Roseland’s current hope is that a Red Line extension will bring new stations to 111th and Eggleston and Michigan and 115th. That, in turn, will bring new residents and new businesses to the neighborhood.

“Wouldn’t be no slow day,” said Mike Smith, a caller in front of Fashion Gear, Inc., 11131 S. Michigan Ave. “Back in the day, there was good money going through here. The corona, people lost their jobs, lost their cars. You get the train coming through, people will get their jobs back.”

Those stations won’t open until 2029 at the earliest, though. In the meantime, it’s worth visiting Roseland just for the doughnuts. Even if you have to take the bus.