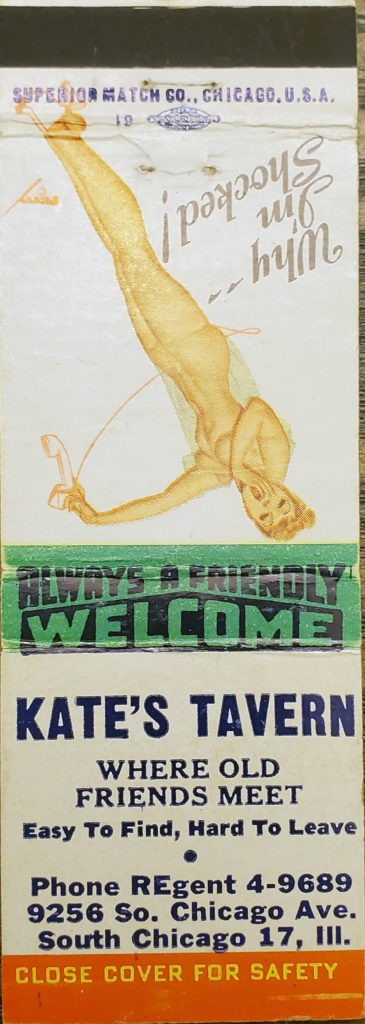

An old matchbook cover arrived in the mail the other day. On the back is a cheesecake drawing of a busty woman. On the front is an advertisement for Kate’s Tavern: “Where Old Friends Meet. Easy To Find. Hard to Leave. Phone REgent 4-9689. 9256 So. Chicago Ave. South Chicago 17, Ill. Please Close Cover For Safety.”

Kate’s Tavern was the bar’s official name, but every sailor on the Great Lakes knew it as Peckerhead Kate’s, and every sailor wanted to drink there when his boat dropped off iron ore at U.S. Steel South Works. Kate was the sailor’s best friend. She called all her customers “peckerhead,” but when a guy was broke and between berths, Kate would loan him a hundred bucks, to tide him over until he got back on a boat — and she never asked for interest. Kate rented out rooms above the tavern to neighborhood transients, and sailors who had no place else to go during the winter. Her tavern was a retirement home for sailors too old or too drunk to work: She gave them two meals a day, and a cot in the basement.

In the summer of 1952, Stanley Graham, a college kid from Ohio, was sailing his first season on the Lakes, as a porter on the B.F. Affleck. When the boat arrived in Chicago, all the old guys in the mess room could talk about was going up the street to Peckerhead Kate’s.

“That goddamned Peckerhead is a case,” a porter announced, after he finished washing the dishes. “Did I ever tell you guys the story about two sailors who were in her bar talking about whether or not she wore falsies? They were talking loud and old Peckerhead heard them. Well, what does she do but go up to them, open up her blouse, and throw a tit out on the bar. She said, ‘Here, you goddamned peckerheads, feel this and see if it’s real.’ And she grabbed the guy’s hand and put it right there.”

“She doesn’t use clean language, but she’s a square shooter,” said the second mate. “A lot of guys on this boat use worse language than she does.”

Stanley and four other sailors piled into a cab for the two-mile ride to Peckerhead Kate’s. It was a narrow wooden building with drawn venetian blinds and a red neon sign beneath the second-story windows: KATE’S TAVERN. Inside, framed photos of Great Lakes steamers hung on the walls. The decor was not the attraction, though. The attraction was Kate. She was a short, stout, red-faced woman, newly married and a new mother. Stanley watched her hustle toward the basement, carrying an armful of blankets for her pensioned sailors. She looked tired, but when she came back upstairs, she woke herself up with two shots of whiskey.

“When I get drunk on beer,” Kate liked to say, “I sober up on whiskey.”

“What boat are you on?” Kate asked Stanley’s shipmate, Butch.

“The Affleck.”

“Here’s to the boys of the old Affleck,” Kate shouted. From behind the bar, she belted out a bawdy tune to which every sailor could sing along.

“Lulu had a baby.

She named him Tiny Tim.

She threw him in the piss pot

To see if he could swim.He sank to the bottom

He floated to the top

Lulu got excited

And grabbed him by the…Cocktail, ginger ale,

Five cents a glass.

If you don’t like it,

You can stick it up your…Ask me no questions,

I’ll tell you no lies.

But if you get hit

With a bucket of shit

Remember to close your eyes.”

“Here’s to Peckerhead Kate, the sailor’s friend,” Butch toasted. Every sailor lifted his glass.

“Shut up, you peckerheads!” Kate said, blushing in gratitude.

Sailors weren’t the only transients who washed up at Peckerhead Kate’s. Her ten rented rooms also housed South Chicago’s neighborhood eccentrics: Fat Judy, a toothless old woman who played the piano; Dancing Charlie, who accompanied her by tinkling ash trays with a spoon or a knife; Go for Broke, a hustler who wore a long wool overcoat, which he opened to display and sell wares he had…acquired from the stores on South Chicago Avenue.

Peckerhead Kate’s was not South Chicago’s only sailor bar, either. Her main competition was Horseface Mary’s, which was across the street from South Works’s main gate. According to sailors who remember Mary, she had a long, ungainly face, which was the source of her nickname; but she also had a beau, a freighter captain who made time with her whenever he docked at South Works. Mary was the sailor’s friend, too: she would drive the lonely men to brothels, and wait outside until they finished their business. Horseface Mary’s, though, was a more forbidding institution than Peckerhead Kate’s. The door was always locked. When a visitor arrived, Mary called out “push the buzzer!” in a raspy voice. Then her German shepherd lunged at the window, barking wildly. Only when Mary called off the dog could a guy come in and get a drink.

The sailor bars are gone now, because the sailors are gone. In Peckerhead Kate’s day, 300 freighters plied the Lakes. Now, less than half that many are sailing, and they have less reason to dock in Chicago. U.S. Steel closed in the 1990s. South Chicago, which was once a 24-hour, neon neighborhood supported by the mill, is less appealing to visitors. When foreign “salties” arrive at the Illinois International Port, often bearing coils of steel, their crews want to Uber downtown to shop for cheap American goods. There’s nothing left of Kate’s but that matchbook, a memento of thousands of boozy nights when the sailor’s friend helped them escape the monotony of life onboard a boat.