Chicago deep-dish pizza was first created at Pizzeria Uno, and its essence lies in its distinctive crust. It turns out there was not just one Uno’s crust, but several as it changed over time. What’s been lost — until now — is the original recipe. The most surprising part of the original dough is how different it is from what we expect deep-dish pizza to be like today.

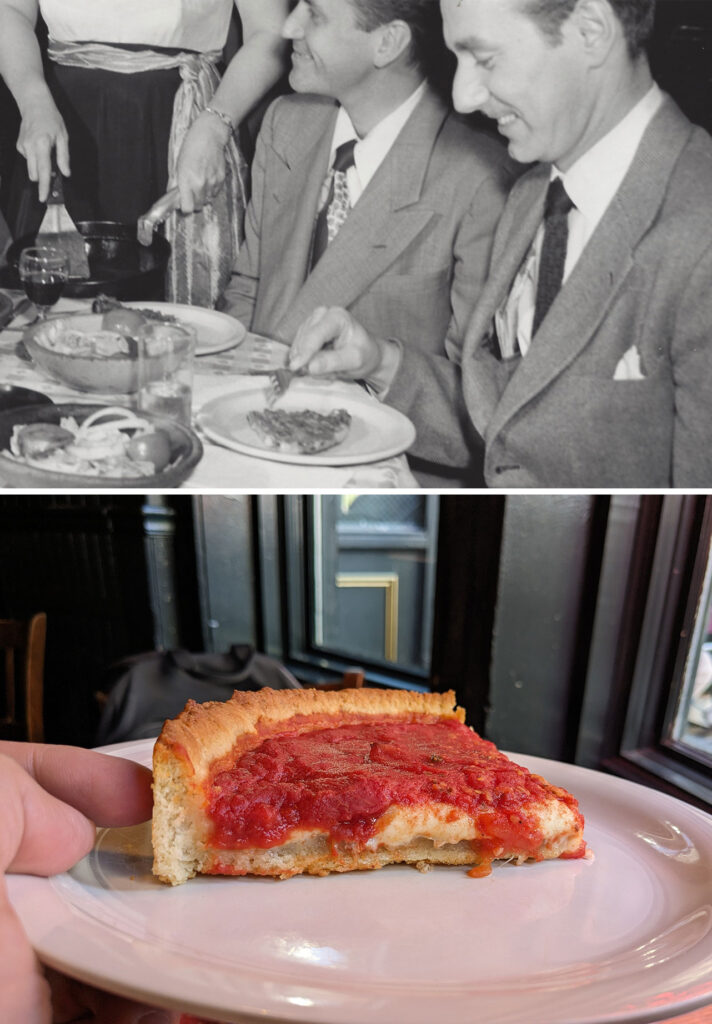

In 2013, I discovered what I believe to be the original deep-dish dough recipe created by Pizzeria Uno’s founder, Richard Riccardo. The recipe, detailed in this article for the first time since 1945, produces a thinner, lighter, vaguely cake-like golden-brown crust that’s distinctly different than the thicker, heavier biscuit-like crust now served at deep-dish pizzerias such as Pizzeria Uno, Gino’s East, and Lou Malnati’s.

Indeed, looking at the entire historical record, we can document at least three different versions of Pizzeria Uno’s deep-dish crust throughout the decades. As time passed — and this is the crucial point — each version moved farther and farther away from what we typically think of as a traditional pizza crust. My research focused on how and why these versions came to be, which eventually led to what we have now. Of course, this also included my own taste-test comparison of the new and old recipes, which highlighted their differences.

Let’s go back to December 1942, to the corner of Wabash and Ohio, to a small abandoned basement tavern that was also once a pizzeria named the Pelican Tap. The new tenants living directly above the abandoned tavern are a recently married couple with their newborn daughter. The 39-year-old father is the painter and restaurateur Richard Riccardo, owner of the famous Riccardo’s Studio Restaurant on Rush Street.

As Riccardo’s then-wife, Mae Juel, recounted in a 1997 unpublished interview with filmmaker Phillip Koch, word reached the Riccardos — probably in the late summer of 1943 — that men were planning to re-open the Pelican. To block this, Riccardo agreed to buy the tavern in the fall, as he later recalled in a 1946 Chicago Sun article, so that “no damn noisy tavern with a jukebox could take it.” His initial Chicago liquor license application notes that he signed a one-year lease for the pizzeria beginning on November 1, 1943, and states that he has no partners.

Even though Chicago’s earliest known pizzeria was established in 1906 — Manhattan had one by 1894 — there were still probably fewer than 13 pizzerias in Chicago in 1943. Riccardo’s bold decision to open a pizzeria was likely influenced by at least two factors: In the early 1940s, the pizzeria business in East Coast cities was booming. Not surprisingly, Riccardo’s customers started asking why his Rush Street restaurant didn’t serve pizza, according to a 1954 Sun-Times article. This was likely on Riccardo’s mind when he walked through the abandoned Pelican Tap for the first time and likely noticed, as an experienced cook would, that the tavern’s pizza oven was probably still connected to the gas line in the tiny kitchen. (It’s even a distinct possibility that the Pelican made pan pizza and the pans were still in the kitchen.) In any case, on or a few days before December 8, 1943, Riccardo opened up what was then called The Pizzeria at 29 E. Ohio St., serving pizza as its sole dish.

There’s been a decades-old controversy about who created deep-dish pizza at Pizzeria Uno. Let’s put this to rest. A 1943 Chicago Sun article was published within days of the pizzeria’s opening, all but telling us who created the initial pizza recipe. It describes Riccardo training the pizzeria’s first cook with “a three-week intensive course in the art of preparing a pizza from the master himself.”

Some writers have argued that Rudy Malnati Sr. — Pizzeria Uno’s former manager — may have created deep-dish pizza, but his timeline suggests otherwise. Malnati was the third manager of the pizzeria, starting in February 1951. Previously, he was a bartender at Riccardo’s Studio Restaurant.

For those still doubting Riccardo’s role, Ike Sewell, who became Riccardo’s de facto partner in February 1944 (Sewell’s wife signed the partnership agreement), had this to say in a 1977 Chicago magazine article: “It wasn’t that I believed in deep dish pizza. It was that I believed in Ric Riccardo. Ric was crazy about beautiful women and crazy about travel…But once he began trying to develop deep-dish pizza, he stayed home…” Supporting Sewell’s comment, a 1954 Chicago Sun-Times article reports that Pizzeria Uno’s recipe was “created during a year of experimentation,” which mirrors Riccardo’s life as he lived above the pizzeria for most of its first year.

After the “year of experimentation,” Riccardo’s recipe was published in a 1945 article in more than 30 mid-market newspapers nationwide. The article states, “Riccardo, an Italian restaurateur of Chicago, noted for his pizza, gives his recipe exclusively to this column.” In addition to the dough, the article describes Riccardo’s sauce recipe and toppings, which include cooked sausage and chopped anchovies. Riccardo’s dough recipe, reproduced, was originally reported in volume units then converted to weights.

Comparing recipes and photographs of Pizzeria Uno’s pizza through the decades, it becomes apparent there were at least three versions of the dough. Version one was probably Riccardo’s original vision for a deep-dish dough, as reported in the 1945 article. This version was noticeably different from the thin-crust pizza served at that time in Chicago, but not radically different. What influenced Riccardo’s creation of this high-fat, high-sugar pan pizza remains a matter of active research. However, there are reports of Chicago Italian-American homes in the 1930s and 1940s using layer cake pans to bake pizza and substituting scalded milk for water in pizza dough recipes. There’s reason to believe this recipe was popular, as Riccardo and Sewell decided by November 1944 to extend the pizzeria’s lease for four years.

Version two was probably a modification in the late 1940s by Pizzeria Uno’s legendary cook, Alice Mae Redmond. To make the dough easier to stretch, she likely added more fat to a recipe that was already high-fat to make a biscuit-like crust. I suspect that shortly after 1945, scalded milk and butter were dropped and replaced by water and olive oil because, in my interviews with the Redmond family, they never mentioned milk and butter as ingredients when they worked at Pizzeria Uno. Incidentally, while interviewing Alice Mae’s now late daughter Lucille, who was also a pizza cook at Uno and Due in the 1950s, I had the benefit of watching her make a Pizzeria Uno pizza as it would have been made in the 1950s. For what it’s worth, her pizza was not nearly as fat-heavy as what’s typically produced today at deep-dish pizzerias.

Finally, version three simply increased the thickness of the pizza and deliberately raised the dough against the sides of the pan, which kept the sauce from burning against the hot pan. This change primarily happened in the 1960s and early 1970s. Interestingly, there is some evidence that the increase in thickness was driven by customer demand, not a top-down decision by management. In any case, the dough ball size increased noticeably over time. For a 9-inch pizza, the 1945 Riccardo recipe yields around an 8.25-ounce dough ball, whereas the current Uno’s dough ball weighs a whopping 14 ounces, a 70% increase.

Given that history, a crucial question remains: Is Riccardo’s original dough better than today’s deep-dish dough? Although similar in some respects, each Chicago deep-dish pizzeria has its own unique take on what a deep-dish dough should be. So, I’ll compare it only to Pizzeria Uno. In my opinion, Riccardo’s original Pizzeria Uno dough is better than the current Pizzeria Uno dough — and I don’t think it’s close.

Why? Fat. Or rather, too much fat. Pizzeria Uno gives out a dough recipe for the home baker wanting to replicate its current deep-dish dough. Combining the amount of vegetable oil in the dough and the pan gives you a baker’s percentage of fat of well over 40% (about four times the fat in Riccardo’s dough). That’s an astonishing amount of fat for a pizza that is then topped with a layer of cheese and often sausage. Is it any wonder customers often struggle to eat one slice?

Undoubtedly, many will disagree with me. Mazel tov. The beauty of publishing this recipe is that we can now let the market decide. Perhaps a new generation of deep-dish pizzerias will embrace the original recipe, and “Riccardo-style” deep dish will become a recognized term. Or, perhaps not. In the meantime, I know what’s going into my oven.

Let’s end by returning to the beginning: Remember Riccardo’s newborn daughter living above the abandoned tavern in December 1942? Baby Riccardo is now 81-year-old Jill Riccardo. What does she think about the latest discoveries that point to her father as the creator of the original deep-dish recipe?

“I always knew Dad created the recipe. I’m unbelievably happy and grateful I’ve lived to see the truth finally come out,” Jill recently told me. Her father was the center of attention at his restaurants, with a knack for provoking controversy with his staff, his customers, and the public at large. But he died young in 1954. How would he react to knowing the little corner pizzeria he opened in 1943 produced a style of pizza that people still argue about today? “He would have been very proud,” Jill told me confidently, “but not at all surprised.”

Riccardo’s 1945 Deep-Dish Pizza Dough Recipe

MAKES: Six 9” deep-dish pizzas

| 2 cups (480 g or 16.93 oz) | Scalded whole milk |

| 1/4 cup (50 g or 1.76 oz) | Sugar |

| 2 tsp (12 g or .42 oz) | Table salt |

| 1/4 cup (59.3 g or 2.09 oz) | Luke warm water |

| 1 cake (7 g or .25 oz) | Yeast (instant dry yeast equivalent) |

| 6 cups (720 g or 25.4 oz) | All-purpose flour, sifted |

| 1/3 cup (75.6 g or 2.67 oz) | Melted unsalted butter or margarine |

1. Measure milk into large mixing bowl. Add sugar and salt. Stir until dissolved. Allow milk to cool to lukewarm. Crumble yeast into lukewarm water. When yeast pops to surface, stir until well mixed. Add to lukewarm milk. Add half the flour and all melted butter or margarine. Beat to a smooth batter. Add remaining flour, sufficient to make a dough that is soft, but not sticky.

2. Turn out on a floured bread board and knead until dough is light and springy. Place in well-greased mixing bowl and set in warm (not hot) place to rise to double its bulk. Then cut the dough down with a sharp knife until quite a bit of the gas has escaped and the bulk is reduced. Knead again to form compact ball of dough. Return to greased bowl. Cover tightly and store in refrigerator.

3. One hour before using, remove from refrigerator. Knead and cut into six pieces. Flatten each into round, very thin pieces about 9 inches in diameter. Arrange on greased pie pans or layer cake tins. Let rise to double its bulk in a warm (never hot) place.

4. Spread the dough with the prepared filling. Over this scatter finely cut cooked sausage or chopped anchovies, and grated cheese. Bake in a 500-degree oven for 15 minutes. Be sure oven is hot when you start. Usually each guest eats one pizza apiece, piping hot without knife or fork.