“These oysters are from New Zealand, and these ones from Alabama,” said Jamie Davis at LTO, the pop-up that has been in residence on the patio at Guild Row all summer. The former had spiky, slate-colored shells and a sweet flavor like a cucumber tea sandwich. The latter has smoother, green-tinged shells and tasted of salt and butter, like a mixture of Korean seaweed snacks and great popcorn. My friend and I eagerly dug in.

The latter oysters, Murder Points, I knew well from my years living in the South. They’re the marquee name among all the new boutique oyster farms in and around Mobile Bay. Lately they’ve started showing up in cool little restaurants in Chicago, like Cellar Door Provisions.

As wild oyster populations are decimated in the Gulf of Mexico and elsewhere, aquaculture farms have taken off anywhere there’s a coast and a supply of clean water. A few years ago, we as diners pretty much had to look for oysters in seafood restaurants — places like Shaw’s Oyster Bar and the late, lamented GT Fish & Oyster. Now neighborhood bistros like Cellar Door, John’s Food & Wine, and Bar Parisette offer oysters as a matter of course, often as a happy-hour enticement.

Yet the new popularity of oysters brings a fair amount of confusion. As I’ve dined around the city I’ve been surprised by how little the service staff and the kitchen know about the oysters they’re serving. I’m amazed by how often restaurants misidentify the two most popular varieties, which in American restaurant shorthand are called Atlantic and Pacific oysters.

It can get a bit complicated. Pacific oysters, Magallana gigas, reproduce easily and can grow quite large, which is why they’re cultivated around the world. They’re the oysters you may get steamed and covered in black bean sauce in Cantonese restaurants, or served in Nayarit-style Mexican seafood places. They can be kind of pleasant, pillowy nothingburgers in terms of flavor when grown in warm waters, but when they come from the Pacific Northwest, the salinity of the colder water plays so well against their natural sweetness and boosts that cucumber flavor fans so love. Further, growers there (such as Kusshi) have learned that they can periodically remove the oysters from the water and tumble them to break off the shell edges. Instead of growing big, they grow deep and cupped.

Now, the complicated part: Not all the great oysters from the Pacific Northwest are Pacific oysters (Kumamoto and Olympia oysters are both separate species), nor do they only grow in the Pacific. After World War II, French marine biologists introduced this species to the Atlantic coast to replace the declining native Ostrea edulis population. When you go to a Parisian oyster bar you’ll feast on local Pacific oysters. Vraiment.

Atlantic oysters have a totally different personality and a more specific sense of place. Crassostrea virginica is the name of the species native to the eastern shoreline and Gulf of Mexico. These bivalves have more of that chewy/slippery texture, can get bracingly salty when grown in briny waters and develop that penny-in-your-mouth metallic flavor that some oyster lovers crave.

I love both varieties, but love them in different ways. The texture and gentle sweetness of Pacific oysters offer such an easygoing pleasure, and I always want a few on any platter before I savor the brine and intense umami of Atlantic oysters. My wife, on the other hand, has no patience for them. She wants that bracing slap of seawater.

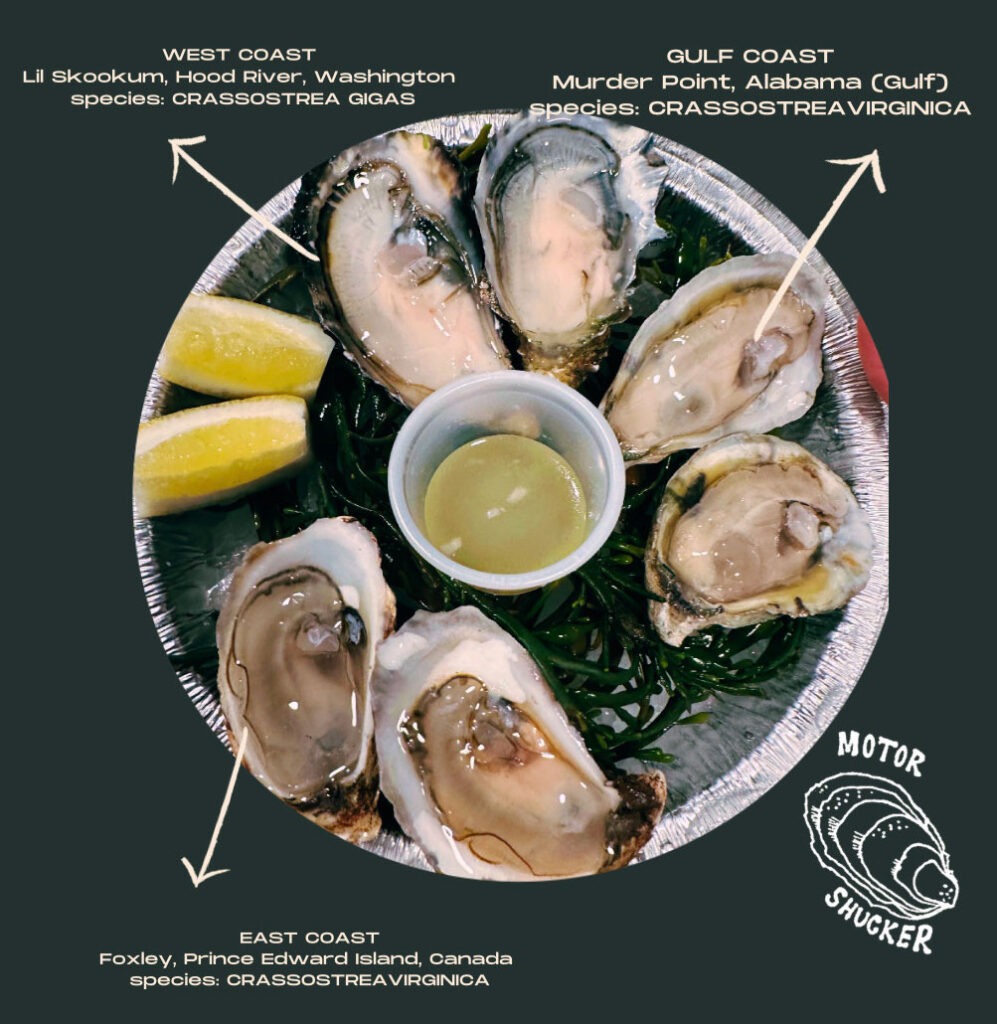

Going back to that platter at LTO, we had both Pacific oysters from New Zealand and Atlantic oysters from Alabama presented with just a bit of mignonette sauce to allow their natural flavors to shine through. Davis, who’s also a principal in Motorshucker, a traveling oyster-focused popup, obviously knows the difference and chooses oysters based on their natural flavor profiles.

Chefs at other restaurants, however, use the oysters as a vehicle for all the creative ingredients they love piling on top. I’ve had everything from fried chicken skin, to finger lime pearls, to passion fruit foam. Pacific oysters generally respond better to all this business but also can get lost in it.

A couple of months ago when I interviewed chef Norman Fenton for my review of Cariño, our discussion of oysters went to a place I wasn’t expecting. Fenton serves a fun bite — an oyster dressed up like a michelada (beer and tomato cocktail) with encapsulated bubbles of Clamato juice, beer foam, and a dusting of Tajin. I tried it twice and found it worked once when the oyster had enough natural brine and umami to stand up to the salty and sweet toppings. The other time it just felt lost; it could’ve been a vegan chicken nugget under all that business. When I pushed Fenton about the provenance of the oysters, he said his supplier picked them out but wasn’t sure where they came from.

“Look, I’m making something that tastes like a michelada,” Fenton said. “I don’t give a fuck about the oyster.”

It’s quite a different approach from that of Kimball House, an Atlanta-area restaurant with my favorite oyster bar anywhere. There you might find words like “chamomile & melon,” “Lay’s potato chips,” or “bay scallops & candied daikon” following the names of different varieties of oysters. No, these aren’t toppings but flavor descriptors; the only seasonings offered are lemon wedges and shallot vinegar served in an eyedropper.

These are exciting times for eating oysters. I just hope that before chefs devise catchy recipes they try the oysters naked and really taste them. To my way of thinking, their own flavors are usually enough.