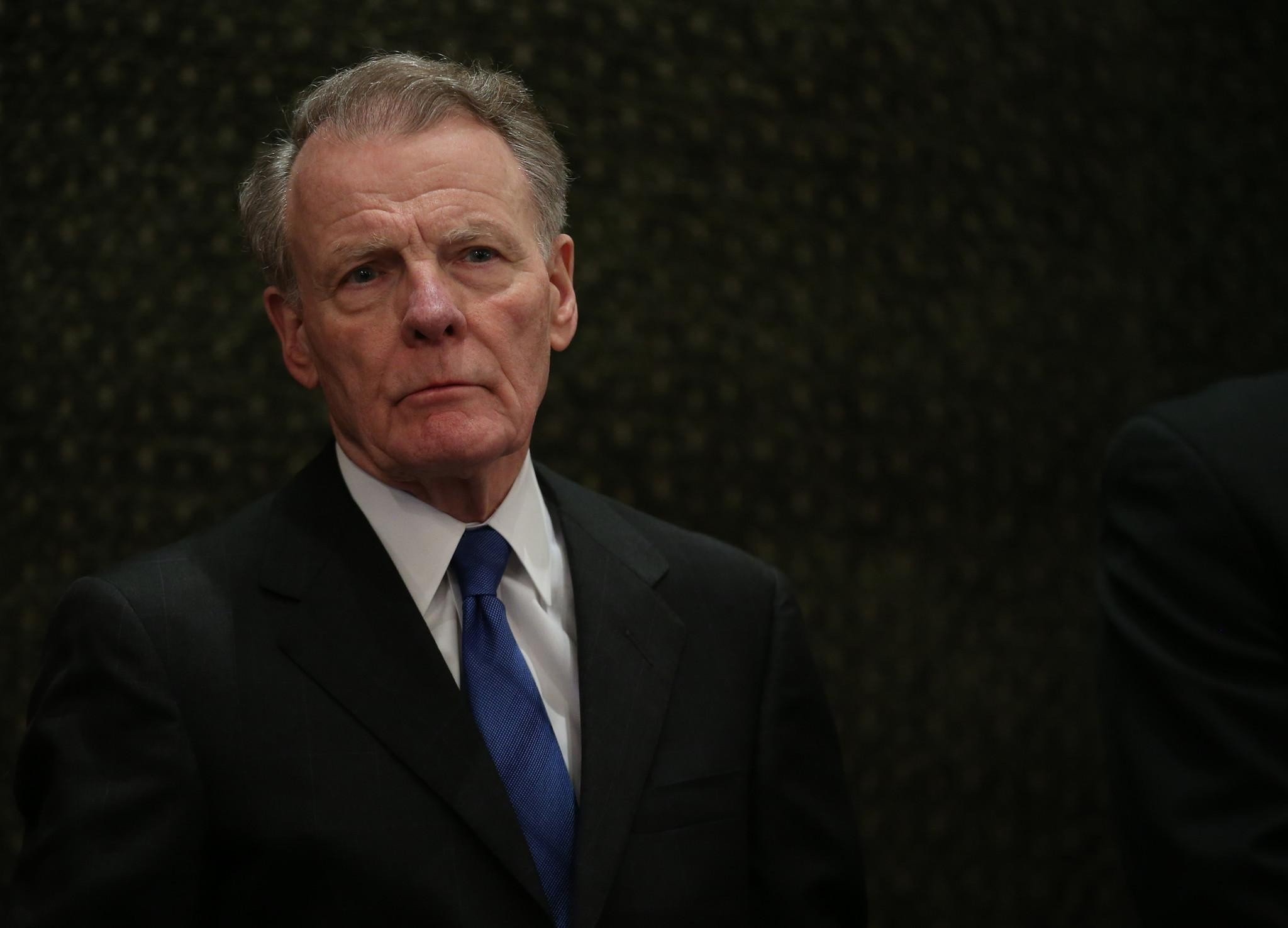

Former state House Speaker Michael Madigan worked hard to turn the suburbs Democratic. The Illinois Democratic Party, which he led, donated millions of dollars to candidates running against Republicans. He gerrymandered suburban districts to elect Democrats. He dispatched his political operatives — the so-called Madigoons — to places like Rolling Meadows and Libertyville, which had never seen a Democratic precinct captain. His strategy worked so well that Lake County, which had been Republican going all the way back to Lincoln, now sends a Democratic majority to the state House. Madigan’s success in the suburbs helped him build a supermajority that should have allowed him to remain speaker as long as he wanted.

Last year, though, after Madigan’s name was connected to the ComEd bribery scandal, the suburban representatives whose careers he had nurtured turned out to be his Brutus and Cassius. The first challenge to his leadership was a letter signed by seven legislators — most from the suburbs — asking him to step down. Rep. Stephanie Kifowit of Aurora announced she would stand against Madigan for speaker.

In adding suburbia to the Democratic base, it turned out, Madigan also created a party that would no longer tolerate his Chicago ward boss style of leadership.

“Suburbanites tend to be less enamored of machine politics,” said Christopher Z. Mooney, a professor of political science at the University of Illinois-Chicago. “Machine politics is about one thing: getting jobs. Suburban voters tend to be more concerned about corruption. They’re a little better off,” and thus don’t need the government jobs political bosses can dole out.

Abortion is important in suburban politics because, in many cases, it’s the issue that caused voters to abandon their ancestral loyalty to the Republican Party.

The old Democratic coalition of Chicago plus Southern Illinois was all about bringing jobs and public works to the two poorest corners of the state. The Downstaters, who were affiliated with the United Mine Workers, were even more rapacious than the Chicagoans. Paul Powell, the famously corrupt House speaker and Secretary of State from Vienna, used to crow, “I can smell the meat a-cookin’!” whenever the subject of state jobs came up.

While many suburban representatives had benefited from Madigan’s operation, the ComEd scandal marked the moment that “a limit had been reached,” Mooney said. “They felt that his usefulness was over. The fact that they were from the suburbs allowed them to have some cover. Madigan’s political tentacles are more effective in the city of Chicago or Cook County.”

Lauren Beth Gash, a former state representative from Highland Park who now serves as chair of the Lake County Democratic Party, says suburbia has less tolerance for machine politics because it has no tradition of machine politics because it only recently converted to the Democratic Party.

“The fact that there have not been Democrats in significant roles in the suburbs means that there hasn’t been a blueprint for machine politics,” Gash said. “They have a structure [in Chicago]. It’s been harder to break out of. We’re making our own rules here.”

Suburbanites haven’t just changed the way politics is conducted within the Democratic Party, they’ve also made certain issues more important to the party. Abortion, for instance. In the 1980s, the Catholic Madigan declared himself “100% pro-life.” In 2019, he supported the Reproductive Health Act, which ensured that abortion will be legal in Illinois if Roe v. Wade is overturned, and declares that a “fetus does not have independent rights under the laws of this state.”

Abortion is important in suburban politics because, in many cases, it’s the issue that caused voters to abandon their ancestral loyalty to the Republican Party.

“Historically, in the suburbs, there have been a lot of of Mark Kirk voters, pro-choice Republican types,” said Evanston Mayor Daniel Biss, a former state representative and state senator. “As the Republican Party moved hard right [on abortion], they moved away from that. The swing issue that flipped a lot of those seats from red to blue was abortion. These suburban legislators feel like that’s an issue that put them in office.”

In 2018, Democrat Terra Costa Howard of Lombard defeated Republican state Rep. Peter Breen, who now serves as senior counsel to the Thomas More Society, an anti-abortion law firm. Howard voted for the Reproductive Health Act — and won a 2020 rematch against Breen.

Gash does not believe the old Democratic coalition would have passed the Reproductive Health Act. In 1998, the party’s nominee for governor was the pro-labor but socially conservative Glenn Poshard, an anti-abortion congressman from Southern Illinois. Poshard got licked in the suburbs (and in some well-off, well-educated lakefront wards in Chicago). Since then, suburbanites have pushed the party toward stronger protections for abortion rights. Madigan tried to adapt to that change in his caucus, but it wasn’t enough to save his speakership.

“The interesting thing to me was the way Madigan changed himself,” Biss said. “He went from proudly calling himself 100 percent pro-life to being very close to the pro-choice movement. He couldn’t change who he was, though, and ultimately it was his brand of politics that was so unpalatable to the suburbs that those same representatives pushed him out.”