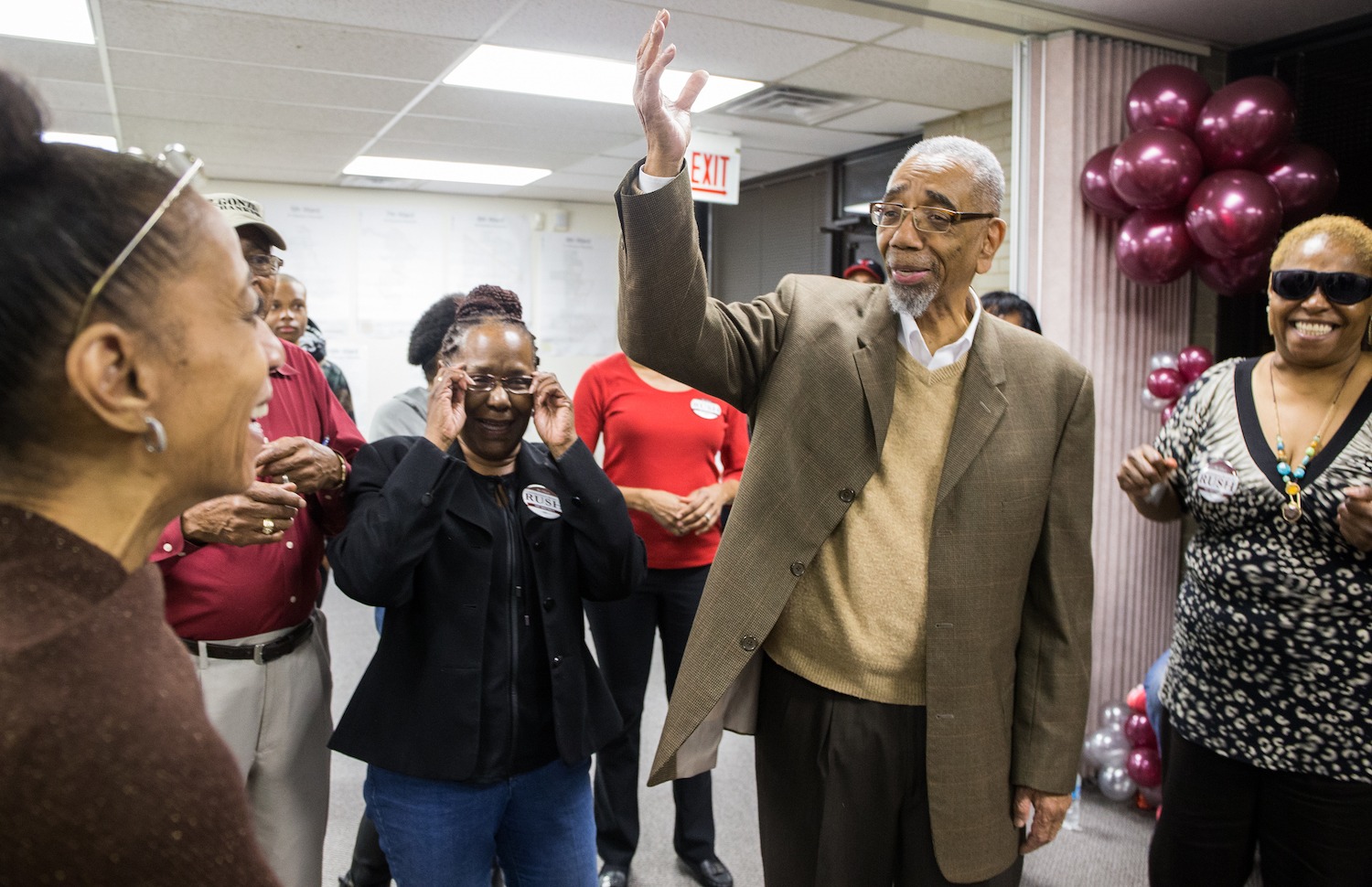

Representative Bobby Lee Rush has just announced he will not be seeking a 16th term in one of Congress’s most historic seats. The 1st District of Illinois, which encompasses most of the South Side, has been represented by an African-American since 1929 — longer than any other district in the nation. The streak was started by Oscar DePriest, a Republican in the days when Black citizens were still loyal to the party of Lincoln.

DePriest was also Chicago’s Black alderman, representing the 2nd Ward — the same office Rush held before going to Washington. DePriest was the pioneer of Black political power in Chicago, Rush his heir, both representing the city’s traditional Black Belt, the “Black Metropolis,” as authors St. Clair Drake and Horace R. Cayton Jr. called it in their 1945 sociological study of the South Side.

From its beginnings in the Black Metropolis, Chicago’s Black political movement grew in power, producing 19 members of Congress — more than any other state — a mayor, two senators, and the first Black president. Harold Washington’s 1983 victory convinced a young Columbia University graduate named Barack Obama that Chicago was a place where an ambitious young Black man could build a political future. (Washington also represented the 1st district before his election as mayor.) From New York, Obama wrote to City Hall, asking for a job. He never heard back, but he made it to Chicago two years after Washington took office, taking a $10,000-a-year job as a South Side community organizer. After Obama returned from Harvard Law School, his first political success was as director of Project Vote!, which registered tens of thousands of Black Chicagoans to vote for Carol Moseley Braun’s 1992 Senate campaign. Obama built his career on the successes of the Black politicians who preceded him.

(Obama’s first and only political failure was his 2000 Democratic primary challenge to Rush. Had he won the race to represent a historically Black congressional district, though, he would never have been elected president.)

“Everybody owes something to Harold Washington, because that was something they never thought could happen,” former Chicago Defender editor Lou Ransom said in 2008. “If Harold can be mayor, what can’t we do? Obama talks about the audacity of hope. That audacity has grown into the notion that a Black man can be president of the United States.”

Black political power in Chicago begat Black political power for the entire nation. But the power that reached its peak with the elections of Washington, Moseley Braun and Obama is beginning to wane, as a result of the city’s declining Black population. When Washington was elected mayor, there were 1.2 million Black voters in Chicago. In the 2020 Census, it was 788,000. The city lost 85,000 Black residents over the last 10 years. In 2010, Black Chicagoans were the city’s largest ethnic bloc; now they’re third, behind whites and Latinos. That has become a casus belli in the City Council’s ward remap: the Black Caucus wants 17 Black-majority wards — down one from the current 18 — and 14 Latino wards. The Latino Caucus wants 15 Latino wards and 15 Black wards, because the two communities’ populations are almost equal.

“Chicago — and neighborhoods like Englewood — offer perhaps the most extreme example of a demographic upheaval reshaping power in cities across the country,” reported POLITICO. “The 2020 census shows Black Americans moving, in huge numbers, out of their longtime homes in Northern and Western cities, and resettling in smaller cities, the suburbs and — in a twist on the Great Migration of the 20th century — the South…The impact on Chicago has been stark, not only in the feeling and identities of neighborhoods like Englewood, but in the power politics of the nation’s third-largest city. Latino residents are beginning to replace Black residents, forcing a realignment in Chicago’s political scene — and a return of the bare-knuckle tribal fights that made Chicago’s City Hall legendary.”

During the congressional redistricting, the mapmakers in Springfield could not find enough voters to maintain three Black-majority districts. Rush’s 1st District is 50.2 percent Black, based on the 2020 Census numbers, which means it won’t be Black majority much longer, assuming it even still is. Danny Davis’s 7th District is 43 percent Black. Robin Kelly’s 2nd District is 57 percent Black, because it covers the south suburbs, where many Black residents have been fleeing from Chicago. (The mapmakers did find enough voters to create a second Latino district, on the Northwest side.)

All this means that, in the future, there will be fewer Black aldermen, fewer Black legislators, and — perhaps — fewer Black congressmen in Chicago. There will, however, be more Latinos. Perhaps the same forces that made us the home of the first Black president will someday make us the home of the first Latino president.