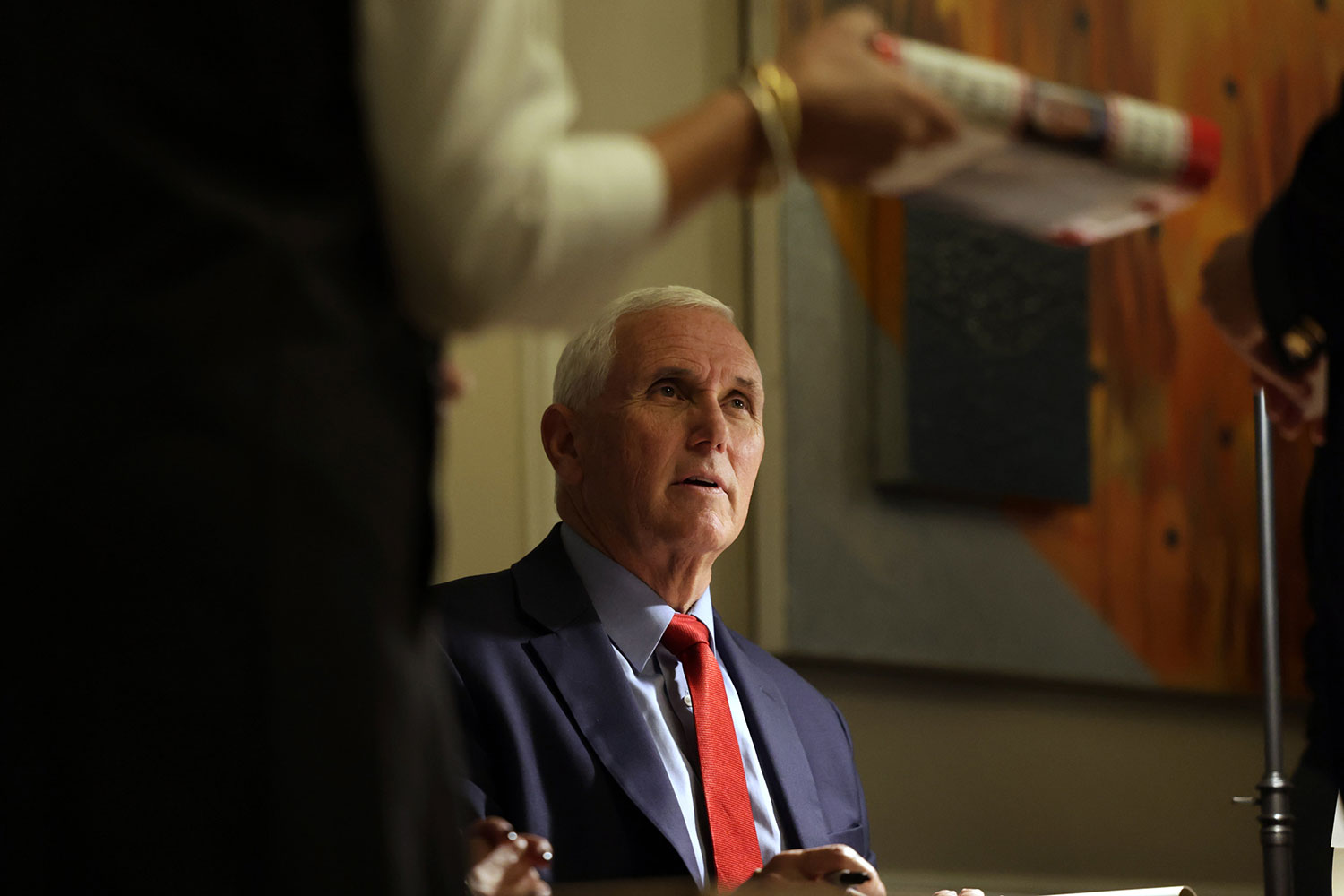

Former Vice President Mike Pence just ended his campaign to move up a notch to the presidency.

“It’s become clear to me: This is not my time,” Pence told the Republican Jewish Coalition’s annual gathering in Las Vegas on Saturday.

Any student of American history could have told you it will never be Mike Pence’s time, and for one reason: Mike Pence is a Hoosier. When the bombastic, insecure Donald Trump was looking for a running mate who would not attract more attention than him — or any attention at all — he looked to Indiana.

Indiana proudly calls itself the “Mother of Vice Presidents” — which suggests that Indiana doesn’t have a lot to be proud of. The state has been home to six vice presidents — Schuyler Colfax, Thomas Hendricks, Charles Fairbanks, Thomas Marshall, Dan Quayle, and Pence — every one as forgettable as the view out the car window on a drive from Chicago to Cincinnati along Interstate 65. In other words, perfectly representative of Indiana. None of those men was among the 15 vice presidents who became president in his own right. Only one Hoosier has held that honor: Benjamin Harrison, who lost the popular vote, lost his rematch with Grover Cleveland, and was named “America’s Most Forgotten President” by New York magazine.

Marshall, the only Hoosier to serve two full terms as vice president (under Woodrow Wilson), once quipped that his state produced so many vice presidents because it is “home of more second-class men than any other state.” No one from Illinois, or any state that borders on Indiana, or any state in the Union, would dispute that. Marshall also liked to tell the story of a man who had two sons: one went to sea and drowned. The other became vice president. “Neither was ever heard from again,” he joked. Indiana honors its obscurities. State Highway 9 is nicknamed the “Highway of Vice Presidents,” because it passes through the hometowns of Hendricks (Shelbyville), Marshall (Columbia City), Quayle (Huntington), and Pence (Columbia).

New York has been home to the most vice presidents (11) but New York would rather brag about Niagara Falls, the Empire State Building, Wall Street, the Yankees, etc., etc.

In 1993, Huntington opened the Dan Quayle Museum, a monument to as second-rate a man who has ever stood a heartbeat away from the presidency. I visited that same year. On display were Dan’s golf bag, Dan’s report card, Dan’s sweater. The Doonesbury cartoonist Garry Trudeau, reporting for Time magazine, called the museum “a sweet, rinky-dink exhibit on the ground floor of an 80-year-old neoclassical building on Warren Street, catty-corner to Dan’s old school,” and wrote that none of the photos of young Quayle could “explain why a not-very-exceptional fellow ascended to the second highest office in the nation.” (Because the vice presidency was designed for not-very-exceptional fellows, and because Indiana is full of them?)

When I visited Huntington again, 20 years later, the museum had been renamed the Quayle Vice Presidential Learning Center, with interpretive exhibits on all 47 (at the time) vice presidents, from Adams to Biden. The curators must have realized that no vice president is worthy of a museum all to himself. Especially not one from Indiana. And especially not the callow Quayle, who took office at the age of 41, and whose most famous quotes include “I believe we are on an irreversible trend toward more freedom and democracy — but that could change,” and “We don’t want to go back to tomorrow, we want to go forward.” Quayle is still the main attraction, though. On the way out, I posed for a photo with a life-size cutout of our 44th vice president.

Anyone who watched late night TV in the early ’90s will recall that Johnny Carson and David Letterman (a fellow Hoosier) had only to say “Dan Quayle” to earn a pre-emptive laugh. Quayle was his own punchline. Like Pence, Quayle attempted to run for president, in 2000. Like Pence, he dropped out before the voting even started, after finishing seventh in the Iowa Straw Poll, with 4 percent of the vote. Quayle now lives in Arizona, where his son, Ben, served a term in Congress, and where he works as an investment banker, using his notoriety to get clients on the phone, because a few bankers are old enough to remember when Dan Quayle was vice president.

Indiana does try to claim credit for a president — and not Harrison. Beneath every “Welcome to Indiana, Crossroads of America” sign is a smaller sign, advertising the state as “Lincoln’s Boyhood Home.” Lincoln spent his formative years, from age 7 to age 21, in Indiana. To become president, though, he had to move across the state line to Illinois. Had he stayed in Indiana, he would only have become Vice President Lincoln.