Stephen A. Douglas has always been a controversial politician. He was the most controversial politician of the 1850s, when he authored the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which allowed settlers in the territories to decide for themselves whether to permit slavery. That inspired a railroad lawyer and former one-term congressman named Abraham Lincoln to get back into politics. He ran for Senate against Douglas in 1858, lost, then defeated him in the presidential election two years later.

Douglas is still controversial today. In 2020, during the George Floyd protests, the University of Chicago removed a plaque and a stone honoring Douglas — one of the university’s founders — because he “profited from his wife’s ownership of a Mississippi plantation where Black people were enslaved.” Then-House Speaker Michael Madigan covered up Douglas’s portrait in the House chamber and removed his statue from the Capitol grounds. The Chicago Park District added an ‘s’ to the name of Douglas Park, thus renaming it after Frederick Douglass. There was even a movement to remove Douglas’s statue from atop his tomb on 35th Street.

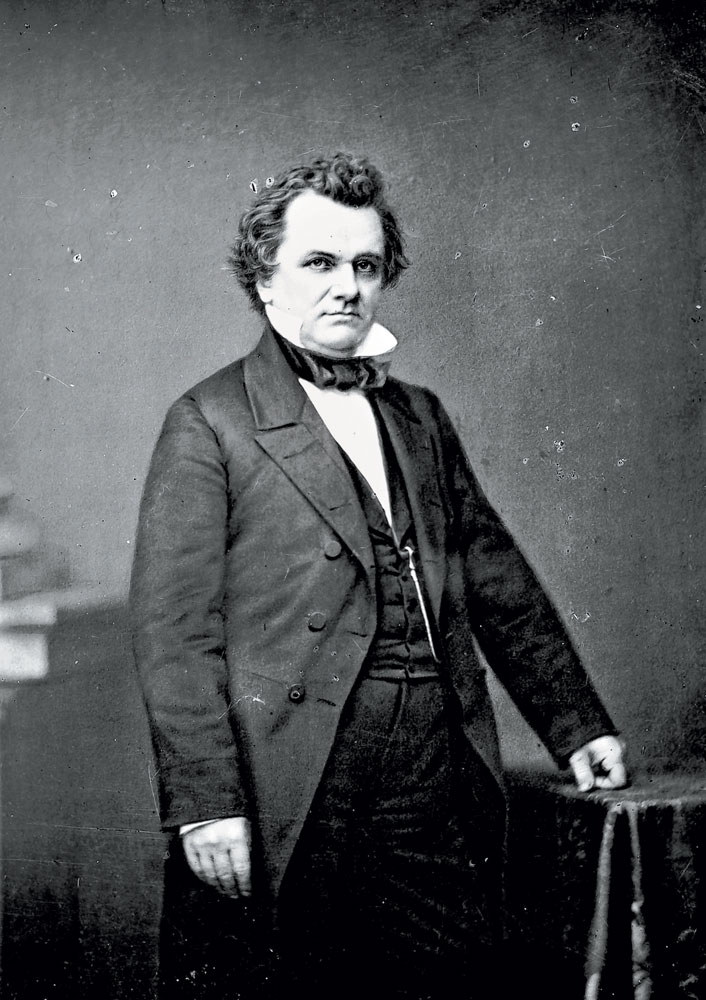

In researching my new book, Chorus of the Union: How Abraham Lincoln and Stephen Douglas Set Aside Their Rivalry to Save the Nation, I discovered that Douglas was far more than a Lincoln antagonist. He was a complicated figure in his day, and he’s a complicated figure now. He played an essential role in making Chicago the metropolis it is today, and an equally important role in building support for Lincoln’s war effort among his skeptical fellow Democrats. Lincoln is a more important figure in the nation’s history, but Douglas was more important to the growth of Chicago and Illinois.

Douglas was not one of Chicago’s founders — he didn’t arrive here until 1847, after his election to the Senate — but his overarching ambition as a senator was in making Chicago the nation’s railroad hub, the gateway to the expanding West. In pursuit of that goal, he was willing to cut deals with slaveholding Southerners. That was politics, and Douglas was the master politician of his era. Douglas’ vision for Chicago as a transportation and industrial powerhouse came to pass. To fulfill it, though, he made multiple compromises with the Slave Power, which ruined first his political career, and then his historical reputation.

Douglas’ first big success as a senator was the Compromise of 1850, a series of bills intended to end Northern and Southern conflicts over slavery. Among other things, it strengthened the Fugitive Slave Law. Orchestrating the Compromise provided Douglas the political cachet to pass the bill he really cared about: the Illinois Central Railroad Tax Act, which brought what was then the world’s longest railroad to Chicago.

The act “began the explosive growth of railroads, the engine for industrial revolution, replacing canals and turnpikes,” wrote Sidney Blumenthal in Wrestling with His Angel, the second volume of his Abraham Lincoln political biography. “Chicago became the nation’s railroad center, where by 1860 fifteen different lines and more than one hundred trains converged daily.”

Douglas championed the Kansas-Nebraska Act as part of his campaign to win Southern support for a transcontinental railroad. According to the official Senate history, Douglas “wanted a northern route via Chicago, but that would take the rail lines through the unorganized Nebraska territory, which lay north of the 1820 Missouri Compromise line where slavery was prohibited.” Repealing the Missouri Compromise was the only way Douglas could get Southerners to vote for his coveted railroad.

But Douglas’s greatest service to the nation was his behavior during and after the 1860 presidential election. In October of that year, after Republicans swept statewide elections in Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Indiana, Douglas realized he had no chance of winning. So he decided to stop campaigning for himself, and to campaign instead against secession, which he feared would follow Lincoln’s election.

“Mr. Lincoln is the next president,” Douglas told his secretary. “We must save the Union. I will go South.”

During the last two weeks of the campaign, Douglas spoke in Nashville, Memphis, Atlanta, Montgomery, and Mobile, telling Southern audiences that “the election of no man on Earth by the people, according to the Constitution, is a cause of breaking up this government.”

When Douglas’s efforts to stop secession failed, he threw himself behind Lincoln and the war effort. Two days after Fort Sumter, he met with Lincoln at the White House to discuss strategy. Lincoln read him a proclamation asking for 75,000 volunteers. Douglas suggested 200,000.

“You do not know the dishonest motives of these men as well as I do,” Douglas said.

“I’ve known Mr. Lincoln a longer time than you have, or than the country has,” Douglas told a friend. “He will come out all right, and we will all stand by him.”

Two weeks later, Douglas returned to Illinois to address the General Assembly in Springfield, in an effort to quash Confederate sympathy in Southern Illinois. In one of the final speeches of his life, Douglas condemned the rebellion, and pleaded with Democrats and Republicans to unite against the Confederacy.

“Do not allow the mortification, growing out of defeat in a partisan struggle, and the elevation of a party to power that we firmly believed to be dangerous to the country — do not let that convert you from patriots to traitors in your own land,” Douglas told his fellow Democrats. “The greater the unanimity the less blood will be shed.”

As the nation’s most prominent War Democrat, Douglas rallied members of his party throughout the North behind Lincoln’s leadership, helping unify the nation against the Confederate rebellion. He was, perhaps, the most magnanimous loser in the history of presidential elections, offering an example that modern politicians would do well to follow. Six weeks later, Douglas died of typhoid fever in a Chicago hotel room. He was buried at Oakenwald, his South Side estate, from which his 96-foot-tall tomb now rises. Douglas didn’t live to see the outcome of the Civil War, but the cause he championed led to the abolition of slavery.

Regardless of the actions of modern-day politicians, Douglas can’t be entirely erased from public commemoration here in Illinois. He is depicted on statues and plaques at the seven Lincoln-Douglas debate sites. If those were removed, Lincoln would look like he was arguing with himself. It is impossible to understand Lincoln’s career without understanding Douglas’s. Their Senate campaign made Lincoln a national figure, providing him the cachet to win the Republican nomination for president. Douglas’s tomb, which is administered by the state, is unlikely to be tampered with, since it’s the senator’s final resting place.

I do miss seeing Douglas’s portrait on the Democratic side of the state House chamber, though. Lincoln and Douglas, looking down together on the legislators, was a reminder of how much the two parties can accomplish when they work together.