Mike Madigan and Ed Burke got into politics the old fashioned way: through their dads.

When he was a law student at Loyola, Madigan introduced himself to Mayor Richard J. Daley as the son of Michael Madigan, a precinct captain and 13th Ward Streets and Sanitation superintendent. That made the young man good people in Daley’s eyes. He found Mike Jr. a job in the city’s law department, then supported his candidacy for the state house.

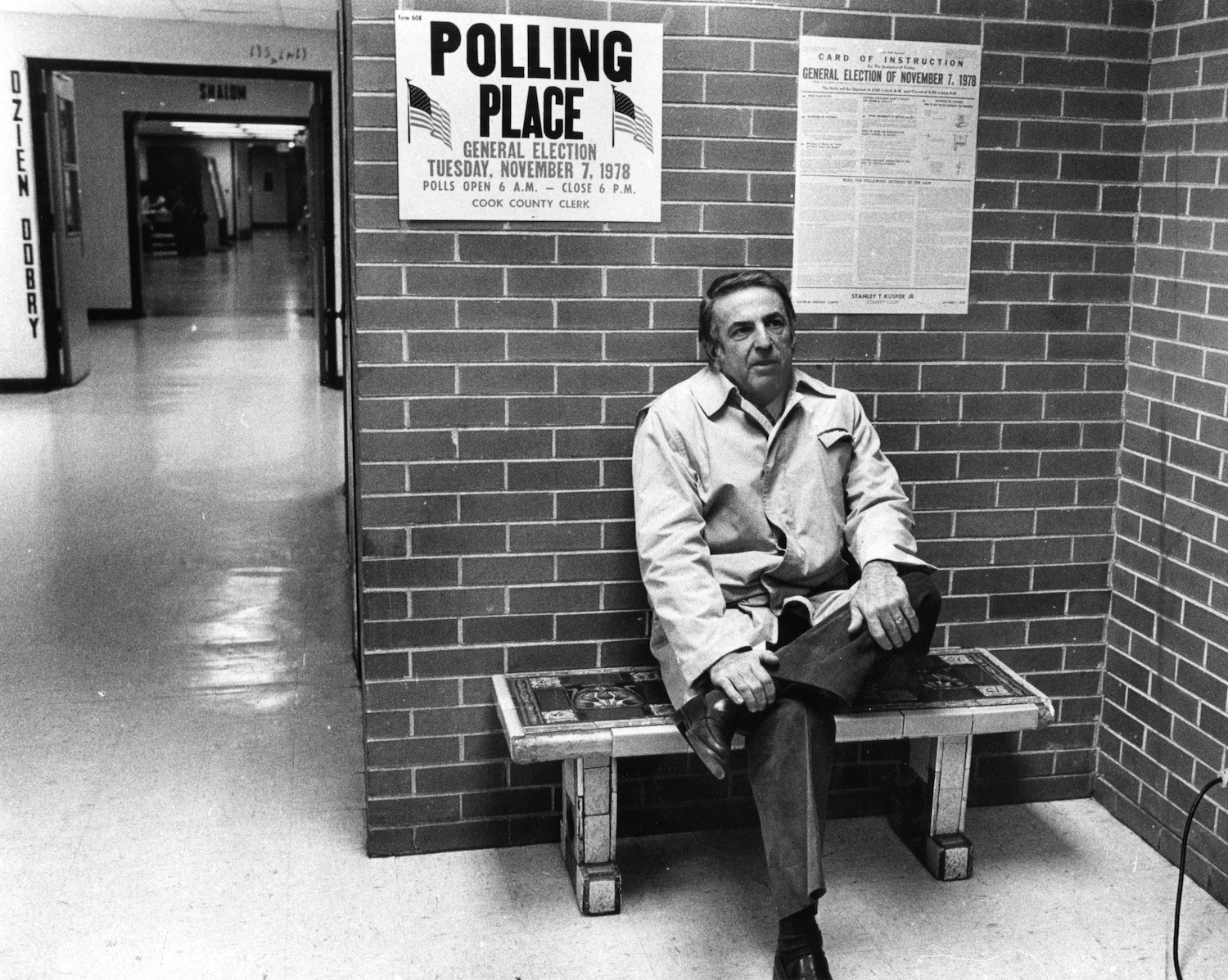

Burke’s filial connection to politics was even more direct: his father, Joseph Burke, was alderman of the 14th Ward. Joe died in 1968. A year later, Ed won a special election to fill his seat, and has held it ever since.

In those days, if you wanted to get ahead in Chicago politics, it helped to be a brat, born and raised in Chicago politics. In 1948, Abner Mikva, a young man from Milwaukee attending the University of Chicago, tried to volunteer at a ward committeeman’s office. He was told, “We don’t want nobody nobody sent.”

Mikva nonetheless went on to a successful career in Chicago politics, serving five terms in the legislature, and four terms in Congress. Back then, he was an outlier, boosted by the transplant-heavy Hyde Park vote—and later by the Evanston vote when the Machine redistricted him out of his alma mater’s neighborhood. Today, he’d be the norm. Consider the origins of some of today’s most successful local politicians.

- Former senator and president Barack Obama: Born and raised in Honolulu.

- Senator Tammy Duckworth: Born in Bangkok, went to high school in Honolulu.

- Cook County Board President and Democratic Party Chairwoman Toni Preckwinkle: Minneapolis, Minnesota.

- Mayor Lori Lightfoot: Massillon, Ohio

- Congresswoman and Illinois Democratic Party Chairwoman Robin Kelly: New York City.

- Former congressman and mayor Rahm Emanuel: Born in Chicago, but raised in Wilmette, where he attended New Trier High School.

- Governor J.B. Pritzker: Atherton, California.

Powerful offices once occupied by Irishmen whose roots in Chicago’s neighborhoods ran generations deep are now almost entirely filled by… transplants. What’s going on?

When Barack Obama arrived in Chicago, in 1985, he knew nobody here except a great-uncle who worked at the University of Chicago library. Not a guy who could help him in politics. Eleven years later, he was a state senator. Eight years after that, a U.S. senator. Four years after that, president. Obama successfully threaded the needle of being in Chicago without being of Chicago. As the city that has produced the most Black members of Congress, Chicago was essential to his political rise. But the fact that Obama was not a traditional Chicago politician meant that John McCain’s accusation that he was “born of the corrupt Chicago political machine” never stuck to him, the way it might have stuck to someone named Daley.

In his runs for Congress, and for mayor, Emanuel’s enemies tried to portray him as a carpetbagging suburban elitist. Nancy Kaszak, Emanuel’s 2002 primary opponent, cut an ad depicting a limousine cruising through the Northwest Side—meant to represent Rahm—then declared, “I’m from here.” During the 2011 mayoral campaign, candidate Miguel del Valle scoffed, “I’m from Humboldt Park. He’s from where—Wilmette, Winnetka? I went to Tuley High, he went to what—New Trier? And Rahm’s tougher than me?” Emanuel never lost an election.

In her campaign for mayor, Lightfoot turned her opponents’ backgrounds in traditional Chicago politics against them. A month and a half before the primary, the feds charged Burke with shaking down a Burger King owner for a permit. Lightfoot cut an ad identifying Preckwinkle, Bill Daley, Susana Mendoza and Gery Chico as the “Burke Four,” because of their ties to the shady alderman. She ran not as a Regular, but as a “goo goo”— a good government reformer—the same label that helped Preckwinkle become an alderman with by cleaning up the vote in Hyde Park and Kenwood in 1991. (The incumbent Preckwinkle defeated, Timothy Evans, now runs the county courts.)

For more than a century, Chicago politics has been based on ethnic alliances. That’s how the experienced politicians were conducting their campaigns. Chico and Mendoza were going for the Latino vote. Willie Wilson was going for the black vote. Daley was going for the white vote. Lightfoot made it into the runoff by selling her anti-corruption message to her fellow goo-goos along the north lakefront—many of them transplants like herself. Then she crushed Preckwinkle by portraying her as a representative of Machine politics.

Why are newcomers to the city beating Chicagoans at their own game? Perhaps it’s because Chicago is a less provincial city than it used to be. Especially since the 1990s, the city has been a magnet for ambitious college-educated professionals from all over the Midwest, and all over the country—and not so much for other age groups. (Preckwinkle and Lightfoot came here to attend the University of Chicago, Kelly to attend Bradley University in Peoria, Duckworth to attend Northern Illinois University.) After making their marks in business, law, academia, and the arts, it was only natural that they would try to conquer politics, too.

In politics, it often helps to be an outsider. Here in the city with the most corrupt political culture in America, it seems to be helping a lot. Lightfoot, who prosecuted bribe-taking aldermen during Operation Silver Shovel, staked her campaign on the fact that Chicagoans were sick of Chicago politicians. She was right. Chicago wanted somebody nobody sent.